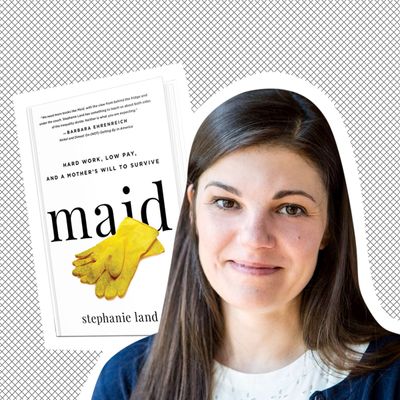

After leaving an abusive relationship and moving into a homeless shelter with her toddler, Stephanie Land began working as a house cleaner for minimum wage. In her debut memoir Maid (out earlier this week from Hachette), Land details the grind required to survive living below the poverty line in America — working as many hours as she could and still, at one point, relying on seven different kinds of government assistance.

Some of Land’s cleaning clients are friendly, while others don’t bother to learn her name. But she becomes intimately familiar with their homes, the ways they live, and the problems they seem to have despite an abundance of that elusive universal balm: money. Eventually, Land is able to afford an apartment, a tiny studio full of mold that makes her daughter constantly sick. Dreaming of a better future, she scrubs even more strangers’ toilets, and sometimes climbs into their empty bathtubs to cry, overwhelmed.

Land spoke with the Cut about her highly anticipated book, the readers she thinks will be most difficult to reach, and public perceptions of poverty.

Who do you most want to read this book?

I mean, every member of the Senate and House. I want them to reach under their seats like an episode of Oprah — “and you get a book!” — that would be my dream. And really the people who firmly believe in this false myth that we have that the American Dream is if you work hard enough you’ll make it. We need to change that so that it’s not just if you work hard enough, it’s if you work hard enough for a living wage, you might have a better chance at making it but there’s no guarantee.

I think a lot of people in the lower-middle class or the upper-working class will be the hardest to break because they’re the ones who have been told this messaging just full of stigmas like, “People on welfare are lazy, they just don’t want to work.” I think that’s where most of the tension is — between people who need government assistance and people who are just over the line and don’t qualify. So I would love to reach people who are just over, or who refuse to accept help because it’s a handout and they’re too proud.

You write a lot in the book about the shame that comes with needing help, and with working hard and still not being able to provide for your daughter. How does it feel now, to be kind of a public face of this experience and to be talking about it so openly?

I think I struggle the most with being called a success story, because that makes it sound like it is a successful system. I think there a lot of what has happened to me in the last few years has been lucky — not everybody can go viral and get an agent and a book deal. I wouldn’t ever want someone to point at me and say, “But look at her, she did it, so it must be working just fine.” That’s not how it goes. I had a book deal to help me out of poverty. I had a lot of things happening that helped me that most people will not have access to as far as that is concerned.

You mention getting an English degree, and you write about that in the book as well — feeling like you couldn’t let yourself do that even though that’s what you really wanted because it wasn’t “practical.” And then in the book there’s this domestic-abuse survivors’ advocate who was pushing you toward it, talking about how great it would be for your then-4-year-old daughter, Mia, who’s a central character in the book, to see you try. I’ve seen you posting on social media, too, about Mia being involved in the book stuff and being really excited about it. Have you been seeing this all through her eyes and talking with her about it?

I try to as much as I can that’s age appropriate — she’s 11. I still don’t know when I’m going to let her read the whole book, but as far as her being involved somewhat to the point that I figure it’s okay for her. She loves it all now, but I don’t know how much she’s going to love it when she’s a teenager or how much is going to bother her about what I wrote about her. I tried to keep writing from a place that was my reaction and my story and not make it her story. In writing the book I was really careful about that because I thought, five years from now, oh my God, what is she going to think about this.

But as far as her witnessing all of this, this is best case scenario of telling your kid that you can achieve your dreams. I hope that she absorbs some of that and goes along in life thinking that she can do whatever she wants, too. That was most of my motivation in going to school for an English degree and being impractical, in my mind, because I wanted her to see that whatever she wants to do, she can. I wanted to at least have her witness me try and to really go for it. I knew if I was stuck in some kind of office job I would probably be a little miserable and so I didn’t want to be that mother.

It seems like it’s been kind of a whirlwind — the book is making a huge splash and it’s not even out yet. What’s the most exciting or surprising thing that’s happened so far in this process?

The most surprising stuff is, to be really honest, I did not expect people to like this book. I thought there would be a population that would be interested in the voyeuristic aspect of it, like, “What is my maid really thinking when she’s in my house?”

But I thought people were going to write it off as whiny, angry, poor person. And then of course when you sit with a book for two years and you have to read through it five or six times through the final edits and copy edits and all of that. By the end of that I was so sick of the book. Just, like, oh my God, nobody is going to like this. So that has been the biggest surprise for me.

And I think I have never really felt like I was a “real writer” because I didn’t follow the route that you’re supposed to. I didn’t go and get the MFA, I didn’t get publications in some esteemed literary journals, and I had to make money, and so I’ve always felt like my writing was kind of cheapened because I wrote to get paid, not for prestige. So I am still surprised when people call it a well-written book. But that’s also part of being an artist. I could have sat with this book for ten years and it would never be perfect so my biggest surprise is just that people like it.

I think I know what you mean, especially with something so vulnerable and personal. It’s totally natural to assume that nobody’s going to care or nobody’s going to like it.

Yeah, and just with all of my experience with internet comment sections and knowing what people think about people who are in my position, I think I expected more of that. And it’s not that I don’t get it. I get comments like that on, whatever, Goodreads and Amazon that it’s a book about all of my bad decision-making and how if I had gone to college when I was 20 then none of this would have happened and if I hadn’t had a baby out of wedlock I would have been fine, and on and on and on. I think I expected more of that reaction instead of support. The support has been surprising. My hope is that it humanizes the millions of people who are living on government assistance, and that people look at them with more compassion after reading it. I have heard responses like that, and I hope that continues.