The designer Batsheva Hay’s high-fashion prairie dresses first attracted widespread attention last year, and looking at them, I experienced a revelation. I felt I better understood myself — my taste, my personal style.

The opposite of this, I remember thinking. My personal style is the opposite of this.

I try to imagine wearing one — happily, voluntarily, in public — and my imagination quails, offering up only a public-speaking-in-underwear nightmare sensation, except it’s me, in a Batsheva dress, on the subway.

But you know what? This is fine. Wearing a trend is one kind of pleasure; not wearing but watching it is another. And the prairie dress is plenty to watch.

In some sense, it may have been inevitable. The pendulum swings — that’s what it does. Nothing looks new or transgressive or surprising forever. Exposed flesh had a good long run as the default provocative gesture in getting dressed as a woman. And now, tugged by the inexorable pull of fashion physics, provocation has swung in the opposite direction. In some sense, the appeal of fashion modesty has to do with broader social realities — it is harder, now, to imagine raising mainstream eyebrows with a short skirt — but at its heart this is a niche phenomenon. Most people do not dress day-to-day with an eye toward aesthetic surprise. Most people are not Olsen twins. Yet those who do strive for frisson via frump are the same ones who exert an outsize influence. And, eventually, the style Zeitgeist that encompassed Phoebe Philo’s Celine, high necklines, shapeless sacks, and Greta Gerwig in a nun’s habit at the Met reached a certain logical extreme in Batsheva.

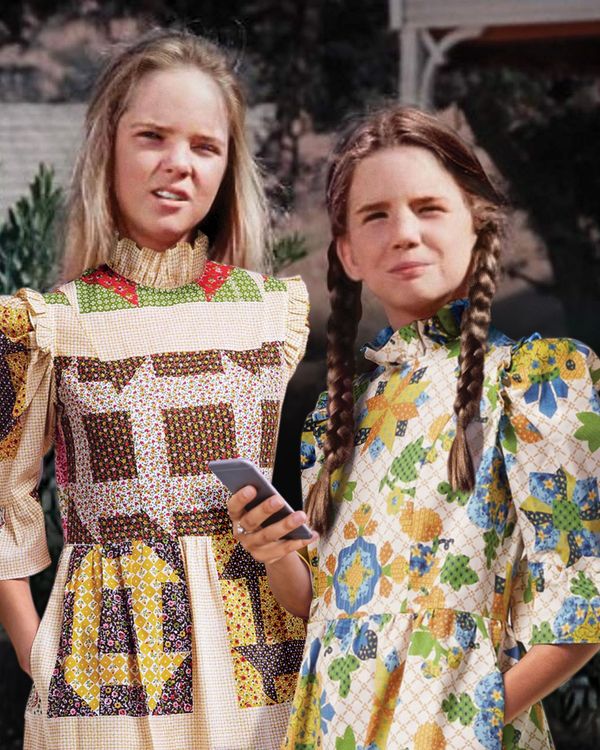

These dresses: They look like Laura Ashley exposed to just a touch of nuclear radiation, and, per the Washington Post, they’re “the most provocative thing in fashion right now.” Vogue: “Vintage Laura Ashley, Betsey Johnson’s Alley Cat, and Gunne Sax.” Women’s Wear Daily: “Anne of Green Gables, Laura Ashley, and Eighties neo-Victoriana.” Haaretz: “Amish Meets Laura Ashley With a Bit of Hasidic Chic.” Indeed, the Batsheva line (launched in 2016) began with a beloved and beat-up Laura Ashley dress that Hay had remade. But her specifications made the details more eccentric, extreme.

Batsheva dresses have lace-trimmed Peter Pan collars or ruffled piecrust collars, and lots of ruffles in general. The necks are high, the shoulders puffed, the bodices stiffly narrow. Their proportions suggest dolls’ clothes — the way their parts wind up strangely proportioned when attempting to scale down to miniature. Most are cotton, in patterns suggestive of childhood quilts and Joann Fabric, but others are rendered in metallic pastels or leopard-print velvet. (Each retails in the range of $400 to $600.) It’s a look that says look at me but also, in its modesty, look away. Batsheva dresses offer conventional girliness drained of any prettiness, any elegance, any beauty: a gender norm codified as its homeliest possible husk.

Maybe my distaste is an indication that I have been successfully provoked. Then again, I try to conjure the physical experience that wearing one of these dresses would involve, and what comes to mind are pit-stains seeping down my sides, wrist ruffles sweeping keyboard filth as I type. These sensations seem objectively bad to me. But there’s something more fundamental going on here, something I’m reacting against. Some trends gain purchase in incremental ways, as modifications you might make to your preexisting style — a new shape of pants, a new brand of bag, a new way of combining your jewelry. The prairie dress is noteworthy for being all-in, demandingly comprehensive in a way that sucks all the air out of the room. It makes an undeniable statement. The statement is “I am wearing a prairie dress.”

I would summarize my internal definition of sartorial comfort as: not feeling like I’m wearing a costume. The Batsheva ethos, meanwhile, is something like: wearing a costume all the time. So what kind of costume is it, exactly? Nostalgia clearly plays a role, at the most basic, dress-up-box level. These are dresses that cater to remembered childhood tastes, as their fans will attest. (Lena Dunham: “They really look like the party dresses that you would’ve wanted when you were 6.”) Then there’s the nostalgia for some hazily remembered past, as suggested by the very term prairie dress — a nostalgia for big-sky Americana. In a Batsheva dress, you are your own American Girl doll, trying on the strictures of another time or place for fun. You inhabit a fantasy past, a world where you can always be the spunky heroine—the one to whom the rules don’t apply.

In this respect, perhaps prairie dressing belongs alongside dirndls and lederhosen (growing in popularity among youth in Bavaria) and Hanfu (a subculture devoted to ancient Han dress in China) as examples of a new global craving for traditionalism. Old-fashioned styles are a respite from the Everlane blandness of contemporary taste, but squint and it’s possible to see the contours of something darker.

“Hanfu is a social scene, and that’s why I’m into it, but it also has deeper levels of national feeling too,” one 29-year-old woman told the Times. She wore “a long blue gown and red cape with a fake fur fringe.”

For her own part, Hay has described finding inspiration in both her mother’s style in the ’70s and the dress codes of religious fundamentalism, from Mennonites and the Amish to Hasidim. A former corporate lawyer educated at Stanford and Georgetown, Hay grew up in a secular family; her husband, a successful fashion photographer, was beginning to embrace Orthodox Judaism around the time they met. Her designs found her grappling with the confines of his faith. During their courtship, the couple staged Hasidic-cosplay photo shoots in South Williamsburg, complete with wig.

Appropriation isn’t really the right rubric here — no one’s taking any apparent offense. And yet, there is a kind of suspect hollowness to these dresses.

In a statement on the brand’s website, Batsheva purports to take “elements symbolic of restraint and repression (high collars, voluminous sleeves and skirts)” and “to extract the strong and beautiful aspects of those styles while rejecting antiquated notions of womanhood.” The logic, I guess, is that if you say you’re rejecting antiquated notions of womanhood, that’s that, even if the untrained observer on the street sees your “elements symbolic of restraint and repression” and assumes (not unreasonably) that you are in some kind of cult. The references and memories that give clothes their evocative power, that make style a kind of communication — these vanish; they were never there. The only meaning is the one you choose. I was reminded of the young Germans quoted in the Times story on Oktoberfest dress-up, quick to protest that they weren’t into that kind of German nationalism. “It has nothing to do with politics,” insisted a 19-year-old in a dirndl. “In Bavaria, we are just proud to be Bavarian.”

I find myself overcome by a weariness of reactionary gestures passed off as provocation. After a solid two decades spent entertaining the argument that any choice a woman made could be counted as feminist provided she chose it, we have claimed a new aesthetic as empowerment. In place of the female chauvinist pig, the feminist sister wife. The desire to believe things can mean only what we say they do is strong.

Detecting something before you can explain it, feeling a rush of gravity as the pendulum swings — that’s the pleasure of following a trend. But don’t underestimate the satisfaction of resisting.

*This article appears in the February 4, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

MORE FROM THE SPRING 2019 FASHION ISSUE

- A Fashion Historian Explains This Season’s Shoes

- This Season’s Monster Blazers Are Part David Byrne, Part Hillary Clinton

- A Trip to the Laundromat With 18 New Yorkers