Earlier this week, the MIT Technology Review covered the “femtech” company NextGen Jane, which is working on a tool that could potentially identify disease using menstrual blood collected from a tampon (“What If You Could Diagnose Endometriosis With a Tampon?”). Almost like a 23andMe test, but for women, and with menstrual tissue instead of spit.

One of the company’s co-founders, Ridhi Tariyal, calls what they’re testing “the menstrualome.” Akin to the microbiome or the genome, the menstrualome as they’ve defined it is the world of information contained within women’s menstrual cycles. Expelled menstrual tissue is “a highly underutilized, underexplored specimen that could really break open women’s reproductive health,” Tariyal told Forbes in 2017. “But to date everyone has thought it’s too gross to engage in.” Also: “Nothing would make us happier than displacing the PAP smear.”

In theory, the mensturalome could reveal clues not just about endometriosis (which often goes undiagnosed but is believed to affect 11 percent or more of reproductive-age women, according to the Office of Women’s Health), but also, perhaps, about STIs, PCOS, certain cancers, and fertility status.

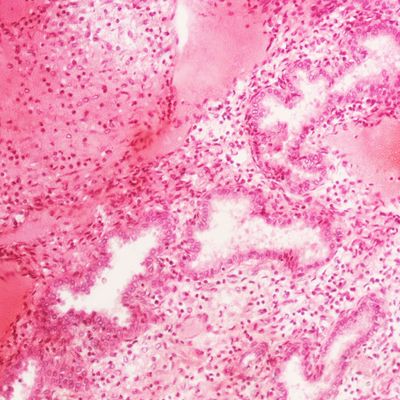

According to the NextGen Jane website: “Every single month during your period, your body is providing you with a natural biopsy when it sheds your endometrial lining. What could we learn if we had the tools to listen?” The site also suggests that users may one day be able to “Trade in your GYN’s speculum and stirrups for organic cotton.”

But can it work? It remains to be seen. So far, the NextGen Jane smart tampon has “shown promise in identifying endometriosis when compared to laparoscopy tests,” according to a recent Ozy story, and more trials are scheduled for later this year (and beyond). Outside of their trials, a 2018 study found that menstrual fluid can be a “useful,” noninvasive diagnostic tool for identifying endometriosis in particular. “Diagnosing diseases from menstrual blood is difficult,” however, as Dayna Evans notes in the MIT Technology Review, and in light of the fall of Theranos, there is heightened skepticism over companies aiming to “reinvent the blood test.”

NextGen Jane, which was founded in 2014, has already raised at least $2.3 million, and the founders are currently trying to raise more to patent a tampon-wringing device. After that, they’d raise more money to run a small trial that could establish whether or not menstrual blood can, in fact, be used for diagnostic purposes. Tariyal estimates, to Evans, that this would take about two years.

Interested menstruators can sign up to be a menstrualome Beta Tester, which presumably entails using one of NextGen Jane’s prototype kits and then sending it back to them, although the testing hasn’t actually started yet. (I signed up and was told, in an automated response: “In the next few months, we will be reaching out to start our beta testing and are excited to engage everyone who has signed up. We will send out more information as we get closer to starting the next phase of our research.”)

The only way this could be more interesting, in my opinion at least, is if they were doing this all with menstrual cups.