Get That Money is an exploration of the many ways we think about our finances — what we earn, what we have, and what we want.

A few years ago, I went through a brief period of financial fantasizing. My money situation wasn’t great. I had student loans to pay and was living at home, working part-time as an administrative assistant. To cope, I began to imagine another life where all my troubles disappeared because I magically won things. I began to enter sweepstakes for island getaways, Le Creuset sets, a year’s worth of groceries. I also began playing the lottery. When my mother saw the Powerball tickets, she frowned. “That’s a waste of money,” she said.

A few weeks later, she sent me an email that contained a spreadsheet. The first column showed the cost of a single lottery ticket, then two, five, ten, twenty. In each subsequent column, she had calculated how much money I would earn if I invested that money in a high-yield savings account or investment fund instead, tracking the compound interest I would receive over one, five, ten, twenty, and fifty years.

This is not unusual. My mother has sent similar emails to my siblings and me about the compound interest we stand to lose if we don’t contribute the maximum in our retirement funds, and news articles about how to make smart investments. She helped me set up my 401(k) when I first started working, and is the person I call when I’m confused about my Roth IRA. This past year, for Christmas, she gave both my sister and me copies of Suze Orman’s book Women & Money, which was funny because I couldn’t believe she hadn’t given it to us already.

Although I grew up firmly upper-middle class, my Asian-American family has always operated on level of frugality familiar to many immigrants. We use stacks of washed takeout containers as Tupperware. We eat at buffets and go for the crab legs instead of rice, noodles, or potatoes. We hold onto bags of all types — plastic, paper, gift — because they can be reused. We strategically time our household purchases around the Bed Bath and Beyond coupons that arrive in the mail every few weeks. And we don’t get rid of anything that might still be functional, from shoeboxes to chipped mugs to single-wrapped toothpicks cribbed from a Chinese restaurant.

It’s a common stereotype that immigrants don’t throw anything away. But a compulsion to save is natural when other backups haven’t always been available. Access to loans, for example, was unthinkable for my grandparents when they first arrived in the 1960s, as they didn’t understand the U.S. credit system. For my family (and, I believe, for a lot of immigrant families), being thrifty is not about greed — instead, it’s about trying to create a financial safety net in a country where we started with none. My mom learned this the hard way from her own mother, and I know she’s trying to pass it along to me.

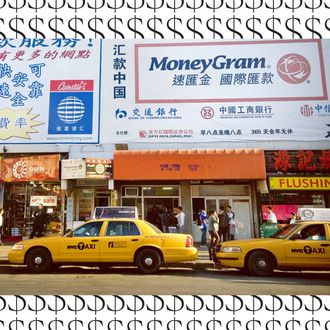

As a teenager, my mom came to America from Taiwan with her parents. Her mother dreamt of becoming a fashion designer in New York City, which she imagined to be much more glamorous than the island where she was born. She did eventually start her own clothing label and, more lucratively, ventured into real-estate development with my grandfather in Flushing, Queens. For awhile, they were an immigrant success story. However, they were uneducated in money management and didn’t understand how to separate personal and business finances, as Chinese and Taiwanese cultures made less of a distinction between the two. They were also prone to excess. I remember when they gave me a beautiful red wool coat for Christmas — a coat I later learned was Burberry, and must have cost hundreds of dollars. I was 7.

Several years later, my grandparents lost most of their money on a risky business venture. They moved into an apartment my parents owned and spent the rest of their lives there, getting by on social security checks and wrestling with medical bills with the help of their three children. When my grandmother passed, amidst her piles of magazines, cosmetics, canned goods, and costume jewelry, we also found a shoebox of cash stashed in the back of a closet, money she had painstakingly hidden away.

My mother, never wanting to suffer as her parents did, taught herself the basics of good financial acumen. When I begged for Steve Madden platform heels as a teenager, she took me to Payless. New school clothes were bought at Daffy’s, where she gave me a strict budget and let me pick through the bins filled with markdowns. She’s tried to pass her hard-won discipline on to my siblings and me, both out of a desire to help us “steer the finance boat towards our goals” (a quote from one of her emails) and an effort to shield us from disaster. Behind every note she sends, behind her packed closets and drawers, I hear a reminder that life can explode in your face. Perhaps that’s one of the legacies that gets passed down in an immigrant household — the understanding that, no matter how safe and secure you might feel, one day you may have to start all over again.

To be frank, despite all my mom’s efforts, I’m still not in a stable financial situation. Years ago I quit a good corporate job with benefits, and since then I’ve cobbled together an income from freelance work, occasional teaching, and writing. It isn’t lost on me that I’ve been able to do this because my parents have provided me with so much, and I occasionally wonder if I will regret it someday. I know my mother does too. Her anxiety about my security — and my own — is something I’ve had to learn to live with. But in many ways, it’s a privilege that my worry isn’t so strong that I’m compelled to act on it. And perhaps that makes my mom happy, too.

I’ve also grown to admire my grandmother’s risk tolerance. Despite her foibles, she demonstrated that big ambitions — and the occasional fantasy — can be worth pursuing. I don’t want to make the same mistakes that she did, but neither do I want to plan a future based on the spectre of what might happen.

And so, I live somewhere in between. I put away what little money I can afford into an investment fund. I hustle for work and apply for grants. I continue to talk myself out of getting a corporate job. I also hoard coils of ribbon and skin-care product samples, but I’ve also started to let go of clothes I haven’t worn in many years, the single-use Wet-Naps I used to take from BBQ restaurants, and the many condiment packets in my fridge. This helps me see the things I cherish right now — books, dresses I adore, photographs — more clearly. I can still dream about a better life for myself, but not at the expense of the one I already have. And of course, I don’t buy lottery tickets anymore.