The eight Mennonite women central to Miriam Toews’s Women Talking (published in the U.S. last week) have given themselves three options: do nothing, stay and fight, or leave. These women have recently learned the real reason they’ve been waking up physically brutalized for two years: It was not, as they’d been told, the consequences of their own wild imaginations or demons called by their sins. It was a group of men, fellow colonists who drugged them with animal tranquilizers and raped them in their beds in the middle of the night.

The extent of the crimes and their aftermath is unveiled in calm, unadorned language, somehow still lively and familiar as a hummingbird. We learn that a 3-year-old is now infected with a sexually transmitted disease, that a 16-year-old girl’s mother is not present because she hung herself after her daughter’s brutal rape, that the mother of the 3-year-old attacked the attackers with a scythe. While the women have given themselves three choices, the male leader of their colony has given them two: forgive the men, or leave. The women have two days to decide.

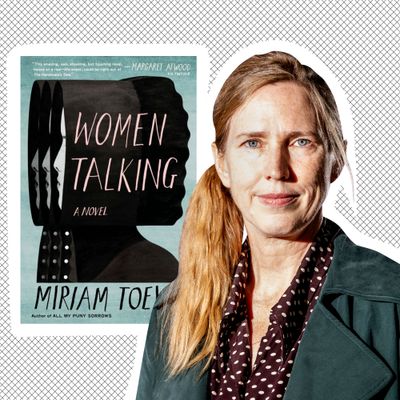

I love Miriam Toews; I don’t know how to disguise my stupid love for her with an attempt to sound smart, so I won’t even try. I believe she’s the best writer of our time. (For the uninitiated: Toews, who has called herself a “secular Mennonnite,” is the literary jewel of Canada. Women Talking is her eighth book.) Her newest book is based on the real-life women of the Manitoba colony in Bolivia, where eight men received long prison sentences for raping hundreds of women and girls from 2005 to 2009.

It might come as a surprise — it did to me — that Women Talking is narrated by a man. A schoolteacher recently returned to the colony after his family’s banishment, August Epps opens the novel by explaining he’s been asked to take the minutes of the women’s discussions about what to do or not do, which take place in a hayloft.

This isn’t the first time Toews has written from a male perspective. Swing Low, published almost 20 years ago, is a memoir of sorts, written in her father’s voice after his death. (Fellow Toews-heads will catch an Easter-egg tribute to him in Women Talking.) It took me a little while to guess at a formal link between the two, to see these narrative choices as a way of witnessing the pain that runs throughout both books.

Women Talking’s male narrator also arises from an element of practicality: In the book’s ultraconservative Molotschna colony, women and girls don’t learn to read or write — which is just one reason the novel is narrated by a man, Toews has explained. (When August points out that the women won’t be able to read what he writes, Ona Friesen, the woman who asked him to take notes, responds with a story about a squirrel and a rabbit. I don’t know what it means.)

What happens? The women talk. “She likes the declarative simplicity of the title,” The New Yorker’s Alexandra Schwartz recently wrote of Toews and her latest. “When people tell her they are surprised to find that her novel mostly just consists of women talking to one another, she thinks, Yeah, well, I warned you.”

The women discuss the implications of each choice, the ramifications on their faith and themselves and the relationship between the two. They consider responding to the attacks “like animals,” then consider what that means: running, or killing their attackers? And are they animals? (Later, one woman muses that they most definitely are not — the colony’s animals receive better treatment.)

“Do you mean that God would allow the parent of the violated child to harbour just a tiny bit of hatred inside her heart?” the mother who wielded the scythe asks. “Just in order to survive?” Another practically scoffs in response: “That’s ridiculous.” The women disagree in one moment and intertwine themselves physically the next. Teenagers braid their hair together, a daughter helps her mother down the hayloft’s ladder. If these women do choose to leave, what and who do they leave behind? How young should a son be to come with them, and how old should he be to stay behind? When asked to weigh in on the danger level of 13- and 14-year-old boys, August tells the women, “Every one of us, male or female, poses a potential threat.”

A readily available resource, pain is a constant source of humor. The teenage girls inflict a fake-suicide prank on the others. One of the older women announces she’s dying, only to realize that dirty glasses, not death, have darkened her vision. The hayloft erupts into laughter as the women joke about the futility of asking the men to leave the colony instead.

The novel’s humor is a welcome counter to its brutality, but it’s also a testament to a complex and ever-present pain. Toews has a canny ability to depict pain by stepping to the side: Swing Low isn’t written from the perspective of a mourning daughter, and Women Talking isn’t written from the perspective of the attacked women. My favorite book of hers, Irma Voth, is written in the first person. “I had never learned how to pray properly,” explains the book’s titular narrator. “It didn’t make sense that God would require me to articulate my pain in order for him to feel it and respond.”

This existential lack of sense is where Toews’s true mastery lies. She’s somehow able to communicate the simplest and most complex aspect of being alive: two conflicting things existing at once. Early on in Women Talking, through a librarian speaking to August Epps, she puts it like this: “Doubt and uncertainty and questioning are inextricably bound together with faith. A rich existence … a way of being in the world.”

As the book comes to a close, August Epps finally comes out and says what he’s spent prior pages hinting at, an origin truth he’s tempted to ask Ona Friesen about in the opening pages. The male narrator has been a living manifestation of impossible female pain — and infinite love — all along. In a way, his choices are the same as the women’s. No matter what, to endure will be a fight. It’s only a matter of deciding what kind.