This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In the spring of 2018, I visited the offices of the millennial/Gen-Z-oriented website babe.net, a sunny loft space in Williamsburg, just around the corner from Vice. Babe.net — now shuttered — was then at the frothy peak of its existence. I made sure to wear my coolest pants.

The site’s managing editor, Eleni Mitzali, a 24-year-old blonde with a sharp bob and half-a-dozen tiny earrings who told me she only listened to podcasts about business strategy and murder, offered me a doughnut while I waited for the day to start. I sat on a small couch, in front of a DIY wall-hanging of Rihanna photos, while Rihanna songs played on a nearby Sonos. Above an archway hung a tweet that a staffer had printed out and enlarged: Overheard in LA (at my dinner table): What the fuck is babe dot net? — Bridget Phetasy (@BridgetPhetasy) January 15, 2018.

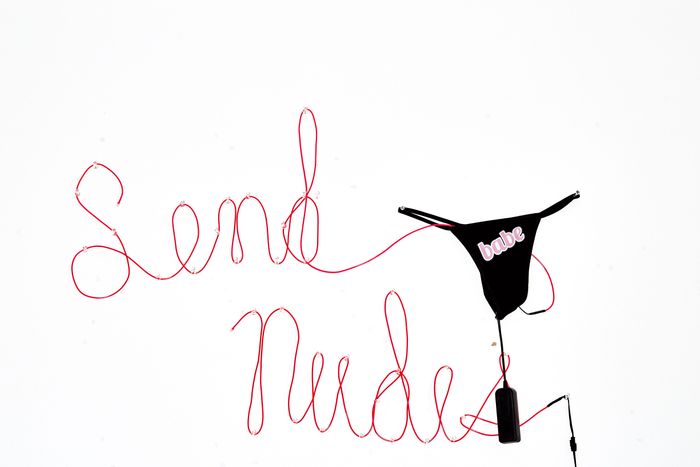

Great question. Babe.net had been humming along, catering to an audience of about 4 million monthly viewers, before it burst through the wall of collective cultural consciousness on a Saturday night that January with both middle fingers up: “I went on a date with Aziz Ansari. It turned into the worst night of my life,” read the instantly viral headline. Babe more typically was full of articles with perfectly demented headlines like: “What Your Favorite Sex Position Says About What Kind of Hoe You Are”; “We Asked Girls How They Prepare for Dick Appointments, and WOW You Guys Are Some Evil Geniuses”; “We Found ’Em: The Last Remaining Beauty Bloggers With Their Original Faces”; “I’m Pretty Sure Kendall Jenner Is Gay, and I Have Evidence for Days.” (And the follow-up, “Taylor Swift Is Gay and I Have Evidence for Days.”) The site once launched a nearly brilliant March Madness–style bracket ranking “ugly hot guys” on a scale of Adam Driver to Ed Sheeran. Its natural stance was nihilist: A babe.net writer asked Jonathan Cheban, a.k.a. “the FoodGod,” what Kim Kardashian’s butthole tasted like and received a belligerent email response that started “Listen to me you little lowlife” and escalated from there. The writer published the screenshots.

Babe launched in 2016 as a vertical of Tab Media, the brainchild of a 29-year-old British journalist named Jack Rivlin. He’d started the site in 2009 while still a 19-year-old student at Cambridge. The Tab, like Babe, relied on content from a network of unpaid student journalists to write a mix of first-person and reported pieces about being young, along with coverage of cultural topics that mattered to 18-to-24-year-olds. In 2017, Rivlin reportedly walked into a meeting with Rupert Murdoch, hung-over, with glitter left on his face from the previous weekend’s music festival — then, according to the Guardian, he walked out with millions of dollars in funding. (Murdoch was one of a handful of investors, including the Knight Foundation, but he didn’t have operational involvement in Tab Media.)

The company scaled up and churned out more copy: Tab Media was already operating on 80 campuses across the U.K. and the U.S., but it expanded its network of contributors and grew babe.net’s editorial team. Babe became its own millennial-pink website, with an independent staff and its own URL, in May 2017. It would have been “babe.com” — so named because that’s what the founding editors liked to call their friends — but the URL already belonged to a camgirl site.

Every internet era gets the insurgent women’s site it deserves. Jezebel broke new ground with an article about a tampon stuck up a writer’s vagina; xoJane, a microgeneration later, outdid that with a cat hairball found in the same cavity. The Betches defended their right, as feminists (or not, who cares), to Brazilian-wax their vaginas, via sorority-girl screeds. Like the Betches, babe.net certainly wasn’t built to be feminist in any kind of traditional sense (after all, Murdoch was a funder and anarchic page-view-getting was the ethos). And yet babe.net was created during an era when to be a woman saying just about anything online was now, theoretically, classified as feminist. When I asked them about it, the site’s writers described theirs as “not the brand of feminism where we have to unconditionally support every woman no matter what she does. Because women can be problematic too.”

The site was frequently and defiantly unsanitized and “real.” Editor Amanda Ross, who was in charge of all the writers, told me she gave new writers links to the old Gawker archives to read in order to nail the tone. (Rarely had the new writers, with an average age of approximately 23, heard of Gawker — much less did they know about its fall.) “It’s like, you know, women have to care about politics, and you have to care about your appearance, but just the right amount,” Ross explained. She had been appointed the editor of babe.net in the fall of 2017, after working with Tab Media for two months. “And you have to care about sexual health but sometimes I just like, Don’t want to use a condom, I wanna use Plan B instead, you know what I mean?”

Babe took a shit on the shibboleths of media, not to mention feminist thought. For a moment, readers were eager to engage in scat-play. But what was always unclear was how much the site’s writers — often with little or no journalistic experience or training — understood the traditions they were turning inside out or ignoring. Nor was it clear whether staff recognized the parallels between the gray-area #MeToo themes of its Ansari piece and the complicated sexual power dynamics of their own office, the ones that would partly lead to the collapse of the site.

Last spring, at the time of my visit, the staff was getting used to the increased attention (and criticism) that had come along with the traffic from the Ansari story. There were some growing pains, maybe even an identity crisis. The site, Ross told me, was pivoting to more serious investigative journalism, though it would still have the content the people craved, like “What percent hoe are you?”

“I turn 25 tomorrow,” she said, groaning. “I’m aging out of the demographic.” Ross sat in the middle of a long table, fielding pitches from her staff and typing on her computer, twirling one of the coils of her blonde mermaid waves. It felt like a TMZ on TV reboot.

“So I think I want to do a story where I ask men to be my slave on Tinder, like as reparations,” said Ari Bines. Bines was a few months into her job at Babe and had quickly become one of site’s top traffic-getters. During college, she’d started her own blog about being big and black; at Babe, she’d added “… and likes to fuck” to her personal brand.

“Yes! Assigned,” yelled Ross. A young woman with a cool-girl Soviet-era mullet pitched a man-in-the-street video asking men if they knew where the clitoris was. Another staff writer wanted to use the corporate card to buy a haunted doll from eBay — for a story, of course.

Katie Way, the reporter who had written the Ansari piece, said she was working on catching pedophiles on Reddit and launching a series of articles by a young woman she’d reported on, Skoop Hernandez, who was imprisoned for killing her mom’s abusive boyfriend. Babe.net had officially tapped Hernandez to be its prison correspondent.

Sitting in the Babe bullpen with the dozen or so staffers working there at the time felt like a version of All the President’s Men, but with Ariana Grande on the radio and schemes to take down fuckboys instead of corrupt politicians. As advertised by the site’s official slogan, for “girls who don’t give a fuck,” Babe women appeared really not to give a fuck. It was thrilling, invigorating — if terrifying — to watch. These kids would never want to work at, like, the Atlantic, would they?

“I would love to work at the Atlantic,” Way said.

At the end of the day, as they often did, the staff transitioned into Thirsty Tuesday happy hour at their regular haunt, an Irish pub called the Craic. It was a chance for them all to hang out and “put drinks on a card that isn’t ours, basically,” explained Ross.

She sat in the center like a sorority-house den mother (she had, in fact, been in a sorority) and held court as the evening slipped into night, and beers turned to shots, and trips to the bathrooms were taken in pairs. Everyone had tiny tattoos and seemed to genuinely like hanging out with each other. The social-media editor, Syra Aburto, taught me the secret to texting quickly when you have long acrylics on. Another staffer sat down next to me, sweetly sipping a tequila sour with a maraschino cherry. “Oh, don’t be fooled,” Ross called out to me, pointing to maraschino-cherry girl. “She’s cute but savage. She’s a Virgo!” Eventually, someone suggested Union Pool, another made a joke (or not) about needing cocaine, and I decided to leave.

I would find out later that most of that day had been carefully calibrated to impress me. “You know how a teacher decorates the classroom on parents’ visiting day?” Bines said recently, laughing. “It was like that.” The Rihanna poster, the framed enlargements of highly trafficked articles on the wall, even the “What the Fuck is babe.net” sign on the archway had all been hung just for my arrival. The U.S. tab.com staffers, who shared the office with babe.net, had been told to go work at another location for the day. Pitches for the features meeting had been prearranged, and my one-on-one meetings with the writers had been so heavily coached Mitzali and Ross could have been producers on The Bachelor. According to Way, things had been tense and chaotic around the time of my visit, as they’d been since the Aziz piece was published. Nobody really wanted to go to happy hour, another staffer told me. The idea of a reporter and photographer coming to the office set off waves of anxiety. But one thing about the day that was true to the actual dynamics of the workplace: The staff all socialized and drank together all the time. And it often got complicated.

In July 2016, Jane, 22, had just finished a day of reporting from the Democratic National Convention. The previous year, she’d started contributing to The Tab, and now she was here on its behalf, in addition to writing for Babe, then still just a vertical rather than a stand-alone site. Jane — not her real name — was a student correspondent from Ohio State University, and she liked the job, even though her editors often urged her to write things like “Embracing Your Walk of Shame,” ignoring her protests that she’d never actually had a walk of shame. And she wasn’t paid, of course, for her work. But she was just happy to have her byline out there. And now, here she was: finally getting to write about topics she cared about — women’s issues and politics — in a more substantial way, and she’d only just graduated. She’d just heard Hillary Clinton speak. She’d had to pay her own way to Philly, but it all felt worth it.

Something was nagging at her, though. The year before, when she’d visited the New York office for spring break — no expenses paid — she’d started a romantic relationship with a top editor of the U.S. edition of The Tab, 27-year-old Joshi Herrmann. Jane had been contributing for about seven months when she’d first met Herrmann, at a post-work happy hour on St. Patrick’s Day, her second day in the office. “It was supposed to be a couple of innocent beers,” she said recently, “but it turned into a complete mess.”

At some point, she recalled, Herrmann started talking to her. “I was just thrilled that this cool guy with a British accent who had written for the Sunday Times thought I was special.” Jane described drinking more, and browning out for periods, until finally, she continued, “I woke up in his apartment the next morning at 6 a.m. I can’t find my wallet, I can’t find my shoes, I can’t find my underwear,” she paused. “And that was the story of me losing my virginity.” She never thought of their relationship or that encounter as anything other than consensual.

Herrman disputes details of her account. “This is a grossly distorted version of what happened, from someone who was a friend of mine for well over a year,” he said. “Almost none of what she says matches what happened that night, and it directly contradicts things she has said and written before.”

The next day, Jane went to the office. “The first thing [a female] editor does is lean on the table and goes, ‘Wow, fucking the boss on the second day? Good move,’” she said. “Everyone was looking at me like I was Monica Lewinsky.” But then that day, they took her to dinner for her birthday at a fancy Indian restaurant. “I was uncomfortable, but it seemed like they were accepting me and seemingly really cared, so I put it aside and kept going.”

At best, her time in the office played like a CW television show’s shiny, sexy version of Brooklyn media life: free beer in the fridge, sexy post-work drinks at dive bars, a sexy open-plan office, where everyone, including the top editors, sat at long tables of swapping ideas rapid-fire. If there was a hierarchy, she couldn’t identify one — nobody felt like a boss, just a friend or a party buddy. As other Babe staffers also told me, the workplace operated like a frat house, where interns and supervisors, underage and of-age, partied together and gossiped about who had hooked up and who slept with whom. The staff didn’t mind, exactly, because it was fun; for many, it was their first job in media and the workplace felt like an extension of college.

Chloe, a babe.net writer (not her real name) who had started at The Tab in fall of 2015 as a campus reporter and then summer intern while she attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, recalled that she’d been surprised by and then a little wary of the boundary-free office culture. One day when she was invited to go out with the staff after work, she Slacked her editor to express concerns: “Lowkey getting wasted with people in the office is weird,” she wrote in a Slack message to her editor, Ross, “but especially bc I’m 20, it’s like hmmm conflict of interest for everyone I feel …”

Ross agreed. “So messy,” she wrote in reply, “but then again, messy is like the tab motto.”

After Jane returned to school to finish her second semester, she continued to keep in contact with Herrmann; he sent her messages, which she shared with the Cut, about how she was nice to wake up with, how hot she was. They flirted and exchanged book recommendations.

Herrmann was the senior editorial presence in the office daily, as a special-projects editor, a job that included selecting which interns worked on special reporting opportunities, like covering the DNC. He’d worked at The Tab when he was at Cambridge and eventually became a junior reporter at The Evening Standard, where he was considered a talented feature writer and reporter. One Babe employee described him as the guy who mostly sat at his computer, looking at numbers, shouting about concurrents “like a Wizard of Oz kind of person,” but his opinion mattered to people. He was the only one in the office who had real-world journalism experience. “It was like, If Joshi is going to work on my story, I will be happy about that because he will give me advice on it,” explained Chloe. But as a result, sometimes she felt his influence was stronger than it should have been, especially as he was one of the few men working at a women’s publication. “The portrayal of being a woman or woman-identified person on Babe was very much through the lens of what Joshi, and by extension the female editors that he had hired, wanted it to be,” she told me. “All of our content just felt very male gaze-y to me. It was like a woman who was obsessed with having sex with men and performing sex for men.”

“Having relationships with people I worked with was a dumb mistake,” said Herrmann. “Before the #MeToo moment, I hadn’t thought through the potential ways in which those relationships can affect more junior colleagues, even if you don’t directly manage them. I regret doing it and I learned from it.”

By the time of the DNC, Jane’s relationship with Herrmann had tapered off. She’d felt a seismic, hurtful shift in his attention. She’d also heard talk that there were other staffers who’d been involved with him. (The Cut confirmed that he’d had relationships with other junior staffers, including another intern.) The rumor mill in the office churned hard — her own name had been caught up in it — and those gossip tidbits and jokes often took place right alongside work-centered conversations on Slack or WhatsApp. For example, in one of the company’s work group chats, dubbed “The Press Pack,” people had been making coded references to Herrmann’s relationships in the middle of a conversation about how cross-posting led to better engagement.

“This is a word chat. Sorry, work,” he’d typed in response.

“Since when has Joshi separated business and pleasure??” a female co-worker in the chat fired back.

In another chat, a male co-worker gave Herrmann a joking nickname that rhymed with editor-in-chief (one that he’d used for an editor-in-chief at an earlier job, too). Herrmann didn’t think it was funny, and he side-messaged Jane on Facebook:

“I’ll sue him for fucking libel and see how hot his media law creds are then,” he’d said in a Facebook message.

“No need to take it any further than putting [him] in his place and leaving it as is,” Jane responded. “By Monday it’ll be a different story to stir about.”

“he said sorry. It’s all good,” Herrmann responded, but then continued. “I mean: How AM I FUCKING PREDATORY???? Rhetorical question you don’t have to answer.”

He followed up with a joking story idea for Jane: “Babe story: ‘Girls, I think we need to stop calling guys we sleep with creeps and predators: it’s fucking hypocritical bullshit.”

The Ansari piece had been about “Grace,” an anonymous 23-year-old woman who had met the actor and comedian at an Emmys after-party, then gone on a date. They drank wine — the piece, full of details, noted that they drank white, even though she preferred red. And then, Grace recounted to Way, at Ansari’s apartment, he aggressively tried to pressure her into sexual acts, disregarding her cues. She thought they were having a romantic night that could be the start of something; he wanted to get straight to it. The post got 2.5 million views within 24 hours, and Babe launched its first newsletter, offering people behind-the-scenes details of the story, if they signed up right away.

The story was some combination of as-told-to and reported piece and morning-after group-chat gossip. It became the flashpoint of discussions about #MeToo. Some writers like Lindy West and Julianne Escobedo Shepherd at Jezebel thoughtfully commented on the messiness of the reporting, on how it left the site and, worse, the victim vulnerable (Grace’s real name was revealed not too long after publication). But they still applauded Babe for moving the feminist conversation forward, for starting a necessary debate about sex that couldn’t be classified as assault or misconduct and didn’t happen in the workplace but was still bad or degrading. But mostly, the Ansari story became a prime piece of evidence for people who believed that the movement was going too far. Critics like Bari Weiss and Caitlin Flanagan slammed the site for botched reporting, for overreach in defining a nonconsensual encounter. Even SNL got in on it. “We are in a post-babe.net universe now,” Kate McKinnon’s character said in a sketch about #MeToo.

The article’s 22-year-old writer, Katie Way, became a mascot of both the site and the #MeToo backlash. Way, a petite brunette dressed like an extra from Reality Bites, had started at Babe three months before publishing the story, fresh out of Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism. She got the Ansari tip from Babe’s social-media accounts, then spent several days working with Grace, five editors, a copy desk, the company’s higher-ups, and lawyers. “I had no idea that so many people were going to read it and interact with it or not read it and interact with it anyway,” she said. “We didn’t write the story for the world or whatever. We wrote it for our core audience. I personally wrote it for Grace.”

CNN anchor Ashleigh Banfield accused Way on air of being a “reckless” journalist; shortly thereafter, a producer reached out via Twitter DM and asked Way to come on Banfield’s show, Headline News. Way, who was “angry, not sleeping, and sick of everyone in the world yelling at her,” she told me later, declined. But she also replied with a message to Banfield: “I hope the 500 retweets on the single news write-up made that burgundy lipstick, bad highlights second-wave feminist has-been feel really relevant for a little while.” Banfield read the message out loud on an episode the next day and Way’s direct message went almost as viral as the original article. The site, meanwhile, responded to the mass criticism with a post that was just a defiant laundry list: “A list of outlets who picked up Grace’s story.”

Way and I met again in a Bushwick bar a month after I’d visited the offices; she’d sent me texts letting me know she’d quit the site with a meme of a girl standing in front of a burning house, grinning slightly. She’d collected a month’s severance from her $35,000 annual salary and was spending time “reading again.” Way had been disappointed by the way the site had handled the aftermath of publication, she told me as she drank her beer, and felt that she’d been pushed out in front of the situation in a way that she wasn’t prepared for. Twitter was a hellscape; people had threatened her mom. She felt like she couldn’t escape the article. She went to parties and women wanted to confess their stories to her, while men wanted to make sure they weren’t like Ansari.

A few days after I hung out at babe.net’s offices, the staff went out to drink together to toast departing team members; Rivlin, the CEO, had decided to shutter the U.S version of The Tab in order to reallocate the money to the cresting babe.net. He was in town to say good-bye to his staffers. The night was an aggressive one. “I didn’t pay for my own drinks the whole night,” staffer Chloe recalled. “I was drinking a lot,” she said, “and browning out.” At some point, she and everyone else ended up back at the company apartment in Williamsburg that Herrmann and Rivlin shared. Chloe found herself dancing with Rivlin and eventually making out with him until another co-worker intervened. One staffer told me that the encounter made her, and the other staffers, deeply uncomfortable. Mitzali, Chloe’s manager, told everyone they had to leave the party. Chloe says that she takes responsibility for her part in the make-out but still felt weird about the whole thing. She burst into tears in the bathroom immediately afterward, and woke up the next morning and texted her boss, Amanda Ross, “I fucked up.”

“I felt like they looked at me differently after this happened,” Chloe said recently.

“We were both drunk, and it was obviously very embarrassing for both of us,” said Rivlin. “It was a mistake, and as the senior member of staff, I should not have let that happen.”

The next day, Chloe went to the Craic and found Herrmann playing pool with a male colleague who had just left the company. They started to recap the events of the previous night. “It was very much just like a joke to them,” she said to me. Herrmann told her, she says, that ‘“I think that if Syra [Aburto] wasn’t there you would have fucked him.’” (Just as adamantly as Chloe remembers hearing it, Herrmann denies ever saying it; the other colleague told me he can’t recall hearing the comment being made.)

The Monday after the incident with Rivlin, Chloe’s manager, Mitzali, pulled her aside to let her know that Rivlin had acknowledged responsibility. Mitzali had told Herrmann and Rivlin that their office behavior had to change — it wasn’t the first time she’d said this — in part because the relationship between Mitzali and the people she managed had been fraying for some time, and this kind of drama made it a lot worse for her. Rivlin never directly apologized to Chloe.

“We were all in our 20s when we were building Babe, and we made some major mistakes along the way, most which of which are on me,” said Herrmann. “I strongly support the Cut’s right to report on our fuck-ups like we reported on many other people’s, but in this instance you have been given a misleading impression of Babe from people who worked for the company for very short periods.”

Babe.net had always partied, had always had drama. This was just what happened when 28-year-olds managed 24-year-olds who managed 20-year-olds, right? But now, in a post-#MeToo climate, after reading all the reactions to the Ansari piece, after thinking so hard about all of it — the morning-after vibe was different. It wasn’t just that the whole thing wasn’t as fun as it used to be. It was bad, maybe, the way they blended work and play and sex and power; some of the writers started to think, how can you keep being a site for “girls who don’t give a fuck,” when you realize that actually, yes, you give some fucks?

And so, a group of five staffers — including three writers who produced much of the site’s content — decided to organize their rage, which had boiled over, at last and all at once. They weren’t just mad about the after-work drunken sloppiness that had seeped into the professional groundwater. They were mad about a lot. They were mad about the whole power imbalance inherent to working for a website that translated their most intimate experiences and identities and beliefs into clicks. They were mad that their female managers didn’t better protect them. When Aburto was asked to star in a video series called Fight Me, she told her managers that the content they wanted her to produce forced her to perform as a caricature of a black woman. Her managers apologized and told her she didn’t have to, but the damage was done. Even now, some former Babe staffers talk about their grievances in the language of raw betrayal; they can’t quite express what was different about the site or the office environment, but the workplace had become, they all make clear, a catastrophe; $30,000-odd a year just wasn’t worth it.

“We would have quit, but financially many of us couldn’t,” Chloe explained. Instead, they decided to appeal to their managers to put into place corrections to the issues they’d identified. The group of five stayed up “mad late,” says Aburto, at the lobby bar of the Public Hotel writing a letter that they presented to management the next day. The letter — excerpted in part below — expressed the group’s perception of racial and gendered power imbalances at the publication, along with their concern over the porousness of boundaries at babe.net.

There is a significant lack of divide between professional and personal relationships — and it

would be one thing to be friends if out-of-work relationships didn’t come into play once in the

office, but it’s very apparent that they DO. …

Sexual misconduct has no place in any office, especially not one that consists primarily and

specifically of young women, for young women. How can we expect to be convincing thought

leaders — especially around consent and sexual violence — among women ages 18 – 24 when

that is the demographic subject to most attention or contact in our own workplace?

They presented the letter, which concluded with a threat to unionize, to Herrmann on May 15, asking to meet him at the Bean, a coffee shop near the office. He read it and returned to the office to have a closed-door meeting with the other managers. None of the women present at the Bean were sure if they should go back to the office.

The company didn’t have a human-resources department (it couldn’t afford one, the company says). There was no clear way to deal with the meltdown, especially since the company’s top authority figures were the ones accused.

The managerial staff — they say upon the advice of an outside HR consultant — decided the best way forward was to have individual meetings with the women who signed the letter, to address specific personal concerns one-by-one. Herrmann ran them. He selected an impartial moderator, news editor Harry Shukman, to witness the proceedings. Each meeting lasted about 90 minutes, during which time Herrmann went through each incident to figure out exactly what had happened. Staffers who had signed the letter were given the results of the meetings verbally at the end of the week. At the end of all the proceedings, most of the claims, which were also directed at Mitzali and Ross, were found to be baseless by Herrmann, who headed up the process.

“It’s simply not true that Joshi was the subject of the complaints or was the wrong person to conduct that investigation — the letter writers were close to him at the time and had made it known that they trusted him,” said Rivlin of the hearings. “He did it with extensive outside guidance, he offered to recuse himself at any moment if complaints about him arose, and he treated everyone extremely fairly. The company identified areas where mistakes were made. It also found that a number of the central allegations were totally baseless.”

Chloe was on vacation — her meeting had been conducted via phone — and when she returned, two of her friends had quit in frustration at the response. She had begun to rethink the babe.net promise of making space for women who didn’t give a fuck. “It always implied that we were at this special place where they could stand us, where it’s possible for us to be these terrible versions of ourselves,” she said. She decided to take her chances that someone else could stand her enough to hire her. She quit, too, without severance. She delivered Postmates, instead, until she found a new job writing for the editorial arm of a Glass Door–like website that rates how friendly — or not — various workplaces are to women.

By June 2018, the remaining staff had downgraded to a walkup office in East Williamsburg. According to Bines, who was let go right after the move, she should have realized the new location was a warning sign: “We were right by the freeway.” There was a new editorial direction: There would still be some blogging — mostly by Ross — but instead the site would be focusing on growing a membership network, in which the company would charge a fee for premium video content, merch, and access to a private Facebook page where readers could ask editors (and each other) advice about things like depression, love, sexuality, self-harm. It was $3 a month, and 1,000 people signed up.

Ross, Mitzali, and an associate editor, Caroline Phinney, who had all been with the company for multiple years and had always operated as a unit in the office, coalesced into an even stronger clique — the last survivors of first-generation Babe. They got matching tattoos — tiny lowercase b’s for Babe — to commemorate their bond to each other and their loyalty to the site. They still hung out at the Craic, with Herrmann, who also got a b tattoo.

But the membership initiative couldn’t turn the business around. According to one high-up employee, the site was “punched in the face” by the Facebook algorithm changing; babe.net stories no longer popped up in people’s feeds, and the site lost traffic. Rivlin had always struggled to sell Babe to advertisers, relying mostly on cash infusions from investors, and now there was even less money coming in from advertisers.

And then, in December, Babe.net quietly ceased making new content. The world didn’t take note. The site officially shuttered in February after failing to secure another round of funding. (It needed, Rivlin estimates, about $1 million to continue operations for another year.) Rivlin tried to sell it, like a failed restaurant with a kitchen all ready to go. All one needed to do was buy the URL to take advantage of its “large distribution, strong brand and reputation,” according to the fact sheet he sent to potential buyers, of which there were a few (mostly queries from porn companies; Tab Media took Babe off the market). For now, the Instagram account lives on like a zombie, run by a shadow network of former staffers who are still emotionally attached.

Way now works at a cannabis site. “Page Six” wrote a “where are they now?” piece about her when she was hired for that job; she couldn’t escape the site and Aziz and her moment of viral fame. We’d talked when she was job-hunting; everyone expected her to be as brash and rude as her email to Banfield when she went to industry mixers or DM’d people about job openings. Her father had encouraged her to apply to law school. She wanted to stay in media, though, maybe even at a legacy publication. “I just long for the warm arms of the adult,” she said with a sigh.

This piece has been updated throughout for clarity and with comment from Herrmann and Rivlin.