It was near closing time at Barney Pressman’s men’s store on January 2, the first working day of 1937. Returns, after-Christmas purchases — an ordinary Saturday. Then, at 8:10 p.m., the gangsters came through the door.

Today, of course, Barney’s is known as Barneys New York. Over its not quite 100 years in business, it lost its apostrophe and became the quintessential luxury department store, run first by three generations of Pressmans and then a couple of corporate owners. (Earlier this week, it declared bankruptcy for the second time and plans to close all but five of its main locations.)

In 1937, though, Barney’s was a successful if slightly dowdy single retailer at 111 Seventh Avenue, one that was just starting to become a local institution. Barney Pressman and his wife, Bertha, had run it for nearly 15 years and had succeeded through canny purchasing that allowed them to run deep discounts. That, plus heavy radio advertising: In the evenings on WNEW, Barney’s commercials played on the police-frequency announcement “Calling all cars” with the lead-in “Calling all men …”

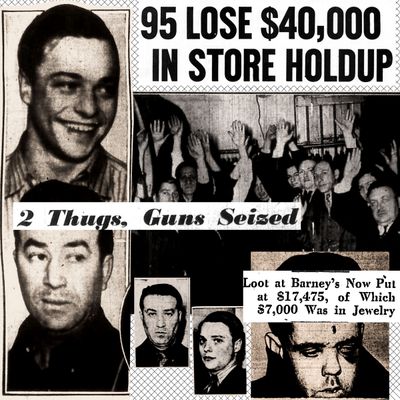

Now the Pressmans needed a real police call. Five crooks had arrived at the store in a pair of automobiles. (The early press accounts incorrectly said eight men.) Two of the robbers carried tommy guns — submachine guns, the kind with drum magazines that you see in old movies of the Capone era — on their shoulders and had pistols in their hands. One guy, wearing a gray fedora, shouted, “It’s a stickup!” He pushed 30 clerks and 60 customers to the rear of the store.

The thieves demanded that the store’s safe be opened and took roughly $10,000 in customers’ checks and cash, some of which had been sorted into payroll envelopes already. One member of the gang, Fred Dunn, started to shake down the customers and employees for cash and valuables — he got $200 from Barney Pressman’s wallet — but the others told him to cut it out, barking, “Lay off the small fry and get the big sugar.”

That would be the jewelry Bertha Pressman was wearing, valued at more than $7,000, which equates to about $125,000 today. Her bracelets and brooch were (according to the Daily News) “stripped from her wrists and throat with deft movements.” Dunn, according to the New York Herald Tribune, grabbed Barney, “whirled him about and then administered an extra-hard kick.” Then the robbers fled, getting away about two minutes before the police arrived at the store. The five men made their respective ways to the basement apartment, at 11 West 65th Street, where Dunn lived with his wife, Sally.

Within the hour, the five became four when Dunn took a bullet to the heart.

Apparently, the gang got into a squabble as they divided the take, because the money that was supposed to be there was, somehow, not. Isidore Lipschitz (sometimes known as Lipschutz; he was the ringleader) and Mike Krusky (who went by several names), faced off against the other bandits, Dunn and Lawrence Mullen, who went by “La-La.” The fifth man, Joseph Stella, was also in the room. When all of them emptied their pockets, they collectively had $840, rather than the thousands they’d expected. Someone, it seemed, was holding out.

Accusations flew, the fight escalated, and Lipschitz knocked La-La unconscious with the butt of a gun. Dunn, who was known to have a temper, probably put up a bigger fight, and Krusky shot him to death. Hours later, when the police made their way to the apartment, they found empty Barney’s pay envelopes scattered about. Dunn was clutching one of them in his hand.

By then, the four survivors had fled and scattered. Krusky and Lipschitz went first to the Bronx and then to Pennsylvania. La-La, his face cut and bruised from the fight, headed to the New York streets, where he slept wherever he could — hallways, basements — for the next couple of days. Eventually, as the pain from the beatings got to him, he turned up at his mother’s apartment on Moylan Place, off the far west end of 125th Street. Stella — who was only 19 — got $140 of the take and took off to the Lower East Side.

All four were caught within three weeks, and it was an act of revenge that led to their capture. Sally Dunn, the wife of the dead man, was just 17 years old, married eight months, and pregnant. (She was an orphan who’d married her husband after a two-week courtship, not knowing he had a criminal record.) As she grieved, she told the police that Krusky had a girlfriend in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, whom he’d said he planned to see that weekend; that and her other leads — plus fingerprints and other evidence found in the apartment on West 65th — led to an eight-state manhunt.

Krusky and Lipschitz were found first and brought back to New York. A couple of days later, police made their way down a fire escape into Mullen’s mother’s apartment, where they found him sleeping on the dining-room floor. After he was hauled into the police station, he collapsed during the lineup. From there, he went the prison ward at Bellevue, where he made a few telephone calls. Stupidly, one of those calls was to Stella, and the police traced the number and picked him up.

Criminal trials were much brisker back then, and all four cases were settled by the end of May. Lipschitz had pretty recently been paroled from Sing Sing and went back there for 15 to 30 years. Krusky got 20 to life, also at Sing Sing. Stella, who already had a record of his own, was sent to the Elmira Reformatory (now Elmira Correctional Facility), which back then focused on rehabilitating younger prisoners; it had been suggested that he would be at risk in a regular prison because he’d given evidence against the other men in his gang. He did only a few years’ time and was paroled in 1941. La-La Mullen tried an insanity defense, but his application was turned down by (and this was a real thing) New York State’s “lunacy commission.” La-La went to Sing Sing, where he’d also served before, this time for a 15-year sentence.

Most of the money, strangely enough, never turned up, at least in public. Maybe it was lost along the way; maybe the total had been inflated for the press. Maybe one of the five crooks had indeed squirreled it away, intending to come back for it much later. Wherever the money went, the robbery itself seems to have been weirdly forgotten, even among the family. The other day, I asked the Vulture contributor Maris Kreizman, who is a descendant of Barney and Bertha Pressman, whether there’s any lore among her relatives about the robbery. Her branch of the family, at least, had never even heard of it — even though it was probably the worst day in the history of the business, worse even than the two bankruptcies.

Anyway, making off with a sack of cash and jewelry seems almost quaint now. The money these days is in the white-collar kind of stickup, where the rent doubles in a couple of years. You can grab a lot more than $840 that way.