Last year, after the birth of my son, I spent ten days in the hospital under siege. My blood pressure had skyrocketed and wouldn’t come down, putting me in imminent danger of having a stroke. A catheter, not my newborn, was planted in my arms, pumping me with magnesium sulfate to protect my brain from high blood pressure–induced seizures. When the doctors finally sent me home, they urged me to stay vigilant. You’re not out of the woods yet they said. I was to swallow more blood pressure pills than an octogenarian, watch for warning signs like headaches or dizziness, and take my pressures twice a day. If I crossed the threshold of 150/90, I’d call Labor and Delivery. Anything much higher and I’d head to the emergency room (which I did).

At home, where my newborn dozed serenely, I was an anxious wreck, spiraling at even the slightest headache, convinced it was a stroke. I imagined my blood was a raging river bursting my vessels. Was this it? Would I be leaving my kids without a mother? My placenta tried to kill me and then it made me crazy.

I had pre-eclampsia, a syndrome that affects about eight percent of all pregnancies in the U.S. each year and is a leading cause of maternal and infant illness and death. The origins of pre-eclampsia aren’t fully understood but can be traced to the placenta’s formation, when the small spiral arteries in the uterine lining transform into highly dilated vessels. Any errors in this process, designed to increase blood flow to the placenta and fetus, can cause serious problems. Sometimes the spiral arteries transform incorrectly, becoming too narrow or blocked and depriving the placenta of blood. When the placenta responds by releasing harmful substances into the mother’s bloodstream, pre-eclampsia can set in, spiking her blood pressure and potentially impairing her kidney and liver function.

Pre-eclampsia rates have soared by 25 percent in the last two decades, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, while maternal mortality has doubled in the same period, earning the U.S. the highest numbers in the developed world. In the hospital, I asked the doctors and nurses caring for me for an explanation. My pregnancy was normal, and I was healthy. Why was this happening? Their responses were vague: “It’s something with your placenta.” “It’s not well understood.”

The Human Placenta Project is working to change that. This $80 million research initiative at the National Institutes of Health is using MRI and other technologies to study how the placenta functions in real-time. The placenta is known for making life, for supplying a fetus with oxygen, water, nutrition, and a waste-removal system. It also acts like a gatekeeper, filtering out pathogens and other harmful substances to protect the fetus. But for all its wonders, the placenta can take life, even the mother’s, when it doesn’t perform as it should. It’s critically important to human health and yet the least understood and least studied of all human organs. Dr. Diana Bianchi, director of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, likes to call it “the Rodney Dangerfield of organs.” Condemned to medical waste, the placenta gets no respect. Almost five years into the Human Placenta Project, researchers are discovering that this transient organ holds the key to treating devastating conditions like pre-eclampsia, prematurity, low birth weight, and stillbirth. They expect new knowledge about the placenta to revolutionize prenatal care.

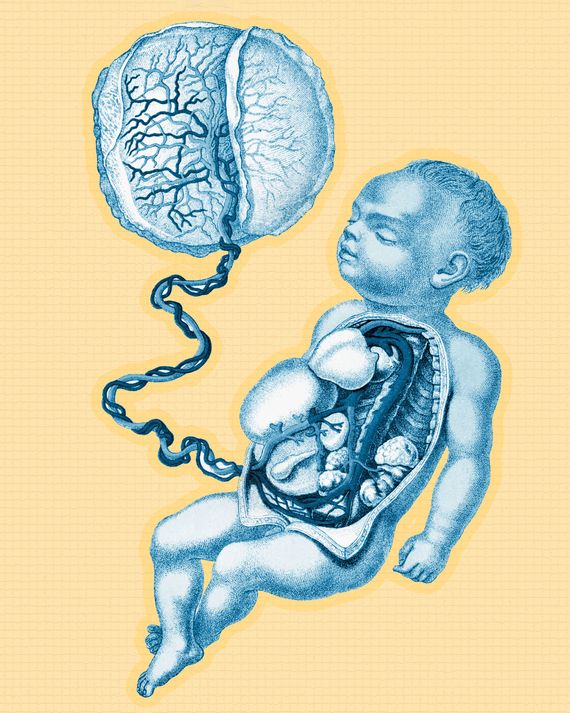

I became obsessed with placentas in the hospital, when no one could tell me what went wrong with mine. Desperate for answers, I asked my mother, a retired pathologist who once scrutinized placentas through a microscope, for a crash course in placentology. “It’s just so bloody” she said, drawing pictures on a napkin. Resembling a large cake dense with blood vessels, the placenta develops from the cells of the embryo, not the mother, as soon as the fertilized egg burrows into the uterine lining. There it grows with a ferocious intensity that some have compared to cancer. Fully formed at about 12 weeks and weighing about a pound at delivery, the placenta is like the Houston Control of a pregnancy. It directs the many tasks that must be performed simultaneously to ensure that the fetus has everything it needs and is prepared for life outside when delivery approaches. The only organ to serve two masters, the placenta makes hormones and other substances that sustain the mother’s pregnancy, enable her milk production, and even target her brain, priming her to care for a baby. In “an extraordinary coup,” writes reproductive immunologist Y. W. Loke in his book Life’s Vital Link: The Astonishing Role of the Placenta, the fetus “manipulates the mother’s physiology and behavior for its own benefit during and after pregnancy.” The placenta is the mechanism it uses to pull off this ingenuous feat.

A placenta made life possible for every person on the planet but for a long time it was tucked away in a corner of medicine in the “niche” of women’s health. Western scientists once characterized this temporary organ as little more than a passive conduit for the shuttling of nutrients from mother to fetus. But many cultures, recognizing something more complex and mysterious at work, have imbued the placenta with special meaning, choosing to honor it, not forget. In Nepal, writes Loke, the placenta is considered a friend to the baby, and in Malaysia, an elder sibling. The indigenous Quinault of the Pacific Northwest refer to the placenta as a grandmother, according to a cross-cultural study of placental practices, while native Icelanders invoke a guardian angel. The Ibo of Nigeria treat it as a dead twin, granting the placenta full burial rites. Traditionally, the Navajo have buried it at home to ensure the return of their children, while Bolivia’s Aymaran fathers hide it underground to protect the baby from the mother’s spirit. In the Maori language, the connection between birth and earth is explicit — whenwua means both placenta and land. In her book The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, Anne Fadiman explains that in the Hmong language, placenta is translated as jacket. Believed to be a person’s first and finest garment, the placenta is buried somewhere safe after delivery. When a Hmong dies, their soul will return to wear this jacket. “If the soul cannot find its jacket, it is condemned to an eternity of wandering, naked and alone.” The placenta brings life and death into close proximity — the birth of a baby marks the end of its journey.

The placenta’s demise is where research begins. Most of our knowledge about the placenta comes from studying it after delivery, after its job is done. As Dr. George R. Saade, chief of obstetrics at the University of Texas Medical Branch, noted in the Times, this is like trying to understand heart disease just by doing an autopsy. Animal models haven’t helped much either, since human placentas are unlike those of many mammals. And while artificial placentas and other models have done wonders, allowing researchers to extrapolate about what happens in people, these aren’t the same as the real thing. Without a way to safely study the placenta in pregnancy, to examine its 270 days in the womb, it has remained elusive.

That is, until recently. The Human Placenta Project brings together researchers in many fields like obstetrics, pathology, radiology, and biophysics, all of them dedicated to studying the placenta during pregnancy instead of after delivery, when it’s too late to avert a crisis. “Maybe we’re doing things completely wrong,” said Dr. Bianchi in an interview. “Maybe we need to know very early on who’s got a malfunctioning placenta, and then direct a lot of treatment toward those pregnancies, whether it’s additional oxygen, or whether it’s some sort of supplement.”

In pregnancy, it’s usually quiet in the beginning and busy at the end. Women with access to prenatal care see a doctor, nurse practitioner, or midwife near the end of the first trimester and then once a month until the due date approaches, when visits become more frequent. But what if pregnancies at risk for adverse outcomes could be identified in the beginning?

Given that experts say a healthy placenta is the single most important factor for producing a healthy baby, it’s shocking that health-care providers, lacking the tools, don’t monitor the placenta at all. This is a problem, explained David Weinberg, who leads the Human Placenta Project, “because just as the fetus is constantly changing, the placenta is also not a static organ.” My OB used ultrasound to track the growth of my fetus and checked my health through blood pressure readings and blood and urine samples. Only after my blood pressure hit the roof, a sign that I already had pre-eclampsia, was there any indication of trouble. And while early delivery was necessary, I was fortunate to be 37 weeks along. Pre-eclampsia can strike at any point after 20 weeks, and once it sets in, the available treatment options are the same ones Downton Abbey’s Lady Sybil faced in 1920: wait or deliver, weighing the risks to the mother’s health against those of a premature baby.

In the Bay Area, where I live, the placenta is famous (or infamous, depending on your view) for other reasons. Having a baby will sooner or later spur a conversation about placentophagy, or maternal consumption of the placenta. This increasingly popular practice has attracted media attention of late, thanks to celebrity boosters like Kim Kardashian West, Alicia Silverstone, and of course, Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop. Proponents say that placenta-eating aids in postpartum recovery, keeps depression at bay, and ramps up a mother’s milk supply. Given the glaring deficiencies in postpartum care in the U.S., especially around mental health care — postpartum depression is the No. 1 complication of childbirth — it’s easy to see the appeal of this “age-old,” “traditional Chinese” remedy.

But is placentophagy really traditional? I’m a historian, so any claims to age-old medicine put my skepticism radar on full blast. I already knew that OBs are adamantly against the practice and that the CDC has warned of the potential for serious illness in newborns, in particular, strep B infection. Then I found Sabine Wilms, a scholar of traditional Chinese medicine who spent years studying what classical Chinese texts have to say about gynecology and postpartum recovery. “The placenta is a very powerful, sacred substance in Chinese medicine and Chinese culture,” she said in an interview. “In the literature, it comes up in the context of how to safely bury it to avoid offending the spirits. There’s no written evidence at all of a woman consuming her own placenta after birth as a mainstream traditional practice in China.” She explained that the placenta does appear in the Chinese materia medica. But always in small amounts in medical prescriptions that are large formulas containing up to 20 ingredients, and for specific clinical purposes, most often for old men with erectile dysfunction. “The placenta was never used as a single ingredient,” she said, “and it was never your own placenta.” The only English-language study of placental practices around the world, carried out by two UNLV anthropologists, supports this view. While many cultures revere the placenta, say the authors, and engage in elaborate rituals for burial and disposal, “the lack of a single unambiguous account of a well-documented tradition of maternal placentophagy is good evidence that it is absent (or at most, extremely rare) as a customary or learned human practice in human societies cross-culturally.”

Something else Wilms said resonated with me. “The placenta is potent, it’s fraught with danger,” she warned. “It can do just as much harm as good.” When I was eight months pregnant, I waddled into the coffee shop I frequent, only to have a well-meaning acquaintance suggest that I encapsulate and ingest my placenta. She called it “nature’s postpartum medicine.” My preference for evidence-based medicine aside, it occurred to me that she was idealizing nature, ignoring that nature can make mistakes, especially when it comes to matters of human reproduction, where so many things can (and do) go wrong. For millions of women around the world each year, the placenta turns out to be more of an adversary than an ally. This is consistent with new biological understandings of pregnancy. Whereas pregnancy was once viewed as a peaceful process, characterized by cooperative interaction between mother and fetus, evolutionary biologists now describe it in terms of conflict. The placenta plays for Team Fetus. And when it doesn’t perform as it should, it can wreak many forms of havoc, not just pre-eclampsia.

Each year intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) affects up to 10 percent of pregnancies in the U.S., resulting in dangerously small babies, and for many families, a protracted ordeal in the NICU. Twenty percent of stillbirths are attributed to IUGR, and the placenta is almost always to blame. But the power of the placenta doesn’t end there, because even long after its sojourn in the womb, it still matters. Some babies born too small experience health problems many years later, and recent studies show that women who have had pre-eclampsia are at a far greater risk for stroke and cardiovascular disease forever. In other words, pregnancy isn’t really over in nine months. One of the main goals of the Human Placenta Project is to understand how the health of the placenta affects the health of mother and baby for the rest of their lives.

Last November, at the annual meeting of the Human Placenta Project in Bethesda, Maryland, investigators presented data showing how subtle abnormalities in the placenta could be detected as early as the first trimester, by working backward from babies they knew were born very small. Findings like these suggest that it’ll soon be possible to identify pregnancies at risk for placental complications, especially growth restriction, in the first few months of pregnancy. They also augur big changes to the way prenatal care is designed. Once clinicians have the tools to monitor the placenta across pregnancy, they’ll be able to catch potential problems before things become dangerous. This would shift the bulk of prenatal appointments into early pregnancy, turning obstetric care upside down.

For researchers, the holy grail is coming up with new tools to study the placenta, and that means getting a better sense of what exactly a healthy, high-functioning placenta looks like. “We still don’t fully understand the range of normal,” said Weinberg, “and we need to define normal to be able to recognize what isn’t.” Some investigators are using MRI to track the flow of oxygen across the placenta, while others are searching for markers, or substances that can be measured in blood or urine, that could signal trouble ahead, even in a seemingly uneventful pregnancy like mine. A groundbreaking five-year study led by Dr. Alfred Abuhamad, chairman of obstetrics and gynecology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, relies on improved ultrasound. Unlike the fuzzy images produced by regular ultrasound, it offers a detailed look at the placenta’s intricate vasculature. When I asked Abuhamid how long it would take for a major study like his to transform what happens inside a doctor’s office, he predicted “a very meaningful impact on clinical care” within five or six years.

Today, for the first time ever, researchers around the world are working with the same intent to demystify the placenta, uncovering the clues it holds to pregnancy and human health. Unlike any other organ, the placenta carries out many diverse functions, and does so simultaneously. Understanding how exactly this new organ grows inside the mother, navigating the maze of her bodily systems to survive and thrive, has major implications for prenatal care but also for other areas of medicine, like immunology and oncology. The science of the placenta matters for everyone. “We seem to be at a moment in history when many researchers are thinking differently about pregnancy,” said Weinberg. “Things are moving very quickly,” he added. “I believe we will see revolutionary advances within the next decade.”