This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

The revolving doors still revolve, the greeters still greet, but the mood at Barneys is glum. The department store — where Andy Warhol and Carrie Bradshaw both shopped — is in bankruptcy; its future is uncertain. It has been actively seeking buyers, and on Thursday evening, after a week of speculation about competing bids, a potential winner emerged: Authentic Brands Group, a licensing company that controls Juicy Couture and Nautica, among others, which announced it would acquire the intellectual property of Barneys New York, pending the approval of a U.S. bankruptcy court, and license it to Saks Fifth Avenue, once Barneys’ competitor. But this may or may not be the final word. Would-be bidders, including a group of investors led by the trade-show owner Sam Ben-Avraham, have until the court hearing on October 31 to try again.

How did we get here? Once upon a time, Barneys was shorthand for a kind of sophistication that didn’t take itself too seriously, a place where New Yorkers would have gone for decades to seek solace or celebration in spending, to buy Alaïa or Dries (though if you needed more than a single name for either, you were probably in the wrong place). At the moment, it is a cautionary tale, a New York treasure mismanaged and overextended, flattened and floated on hedge-fund dollars. Days before bids were to be placed to determine the company’s ownership, the Madison Avenue location was not empty, but the shoppers milling, the tourists and the artists and the idle rich — look, there’s the Met-bound countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo browsing sunglasses with his mother! — milled under a cloud. “What will happen?” some were overheard to say. And, a little more shrewdly, “If Barneys is going under, is anything on sale?”

“My favorite stores were Bendel’s, Barneys, and Bergdorf’s,” said Helen Sant’Andrea, 67, browsing with her daughter, Ellis, 31. Bendel’s is gone (it closed earlier this year, after 123 years), and Barneys as we know it may well go next. “This is now another great store going by the wayside. I told my millennial daughter here, ‘You have to stop buying online! You have to go to the stores and look at the merchandise! Shopping used to be something to do, an experience.”

“I sort of understand why the retailers are shutting down,” Ellis said. “There’s, like, $700 shorts just kind of in a pile right here. Everything’s kind of messy. It doesn’t feel special. It’s not that different from being in Zara.”

Not that different from Zara is a shot to the heart of Barneys, whose eccentricity was once both irreplicable and widely imitated. Founded as a men’s discount clothier in 1923 by Barney Pressman, the “Cut-Rate King,” in the hands of Barney’s son, Fred, and grandson Gene, Barneys eventually added womenswear and home goods and upscaled itself into a temple of only–in–New York esoterica, often before it went both mainstream and worldwide: Giorgio Armani suits before they were anywhere else in America, Comme des Garçons long before Rei Kawakubo and her creations were enshrined in the Met. “It was the place to be,” said Cathy Paul, who worked for the Pressmans in the early ’80s, when Barneys was a single store on 17th Street and Seventh Avenue. “People wanted to be in there — the designers and the creative people.” Customers did, too: “You treasured your things from Barneys,” Paul said.

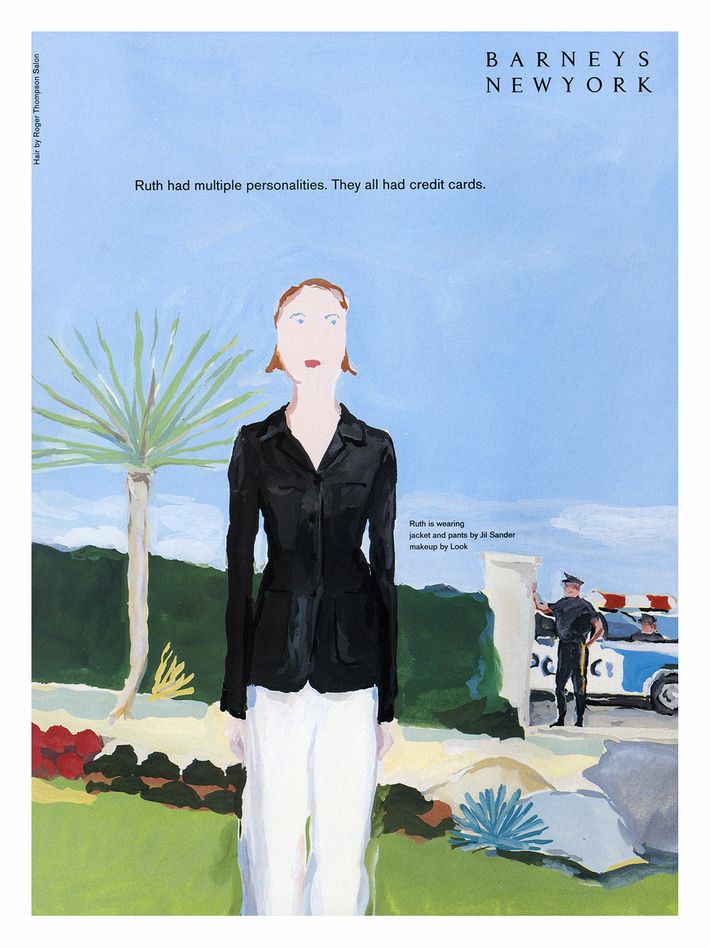

Through the ’80s and ’90s, Barneys set the tone, tongue and cheek never far apart. Simon Doonan, the store’s creative director, made windows of such twisted whimsy that they were nearly performance art: a costumed Sigmund Freud performing analysis, a mannequin Madonna — Material Girl, not Virgin Mother. (The real Madonna once appeared in a fashion show–cum–live auction held to celebrate the opening of Barneys’ women’s store in 1986, the one-of-a-kind jean jacket off her back sold to benefit the nearby St. Vincent’s AIDS clinic.) To shop there was to declare yourself a Barneys person, off-kilter as that might be. (The late style arbiter Glenn O’Brien, who spent years writing the store’s pithy ads, nailed the social anthropology: “Ruth had multiple personalities. They all had credit cards.”)

Barneys was a pleasure palace of downtown cosmopolitanism — winding Andrée Putman staircase and all — a world away from the uptown sheen of Fifth Avenue, even when it eventually added a Madison Avenue store in 1993. When I was a kid, my mother marched me straight past the Rock Center tree to the Barneys windows at Christmastime. This week, I asked her why. “I didn’t always understand the windows but did know that I wanted to,” she said, “in order to be part of that exciting and forbidden insiders’ club.”

It is not news that department stores are struggling. Neiman Marcus’s sales have risen and fallen over the last few years, and it is contending with nearly $5 billion in debt. Nordstrom, which opened its mammoth new women’s store in midtown Manhattan this week with a party as large as a rave, has also been reporting consecutive year-over-year revenue declines. But the situation has felt especially grim for Barneys, which is more of an acquired taste than its competitors. Not that this is the first time it has faced extinction. Barneys filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 1996, making front-page news at the time. By 1999 the Pressmans were largely out, and ownership has changed hands several times since; past owners include Jones Apparel Group and Istithmar, the sovereign-wealth fund of Dubai, which still has a small stake. Until the bankruptcy filing, its majority stakeholder was Perry Capital, the since-shuttered hedge fund that was run by financier Richard Perry, now the chairman of Barneys New York, Inc. (Perry’s wife, Lisa, makes pop art–splashed, vintage-inspired fashion that is sold at Barneys.) Perry Capital took control of Barneys in 2012 when, as its biggest bondholder, the company swapped its debt for equity, allowing Barneys to avoid bankruptcy.

By the time Perry took over, Barneys was a long way from a cozy family business. It was extended broadly with a network of locations across the country: smaller than some of its competitors but still diffuse for what was essentially a specialty store. Mark Lee, a veteran of Yves Saint Laurent and Gucci, had been named CEO in 2010. Under Lee, several longtime executives were replaced. Doonan was nudged from his creative-director role to a more amorphous ambassadorial one, and Dennis Freedman, the former creative director of W magazine, stewarded a redesign to make Barneys sleeker, chicer, and a bit chillier. A former sales associate described the customer reaction as “visceral.” “There used to be a beautiful, beautiful wall of fish,” said a current sales associate, referring to the famous fish tanks on the sales floor. “They tore that down. That was the beginning of the end. When it turned into a black-and-white, stern store, the humor went out. It used to be Barneys was luxury, wit … The wit in it has gone out.” A salesperson who has since left lamented the acres of marble that seemed to swallow up all product it was meant to display. “All of a sudden, it became flat and boring,” the person said. (Freedman has since left the store and declined to be interviewed for this article. None of Barneys’ current employees, and few of its former ones, would speak on the record, fearing retribution.)

Lee brought in his former lieutenants from Gucci, including Daniella Vitale, who joined as chief merchant and executive vice-president in 2010. Barneys’ new look was less unique than it had once been, and the sharpness of the Barneys buy, its onetime calling card, softened. Its distinctive point of view seemed to be slipping away. “So many bad decisions were made. No advice was ever asked,” said a longtime associate. “They really wouldn’t come up with their own ideas; they’d follow what Bergdorf’s or Saks was doing. This is outrageous! We’re Barneys.”

Barneys’ imprimatur could still make a designer a star; the L.A. designer Mike Amiri credited Barneys with catapulting him to the big leagues when the store bought his collection and hung it alongside those of his larger counterparts, the European luxury brands. “Barneys trusted Amiri from day one,” he said over coffee recently. “They understood my vision of creating a luxury powerhouse.” In short order, Amiri was one of the retailer’s top-performing men’s brands. But Barneys’ aggressiveness in demanding the exclusivity it prided itself on, and its dealings with designers it carried, could also alienate those who couldn’t afford to put all their eggs in Barneys’ basket. Fallon jeweler Dana Lorenz wrote on Instagram this week that she “stopped selling to Barneys because of their practice of shackling anyone smaller than Prada into exclusivity … They have been not paying people for years, and backing them into a corner anytime any other larger retailer shows interest. Let me tell you, you will not grow your business if you sell your soul to Barneys.”

Vitale took over from Lee, her mentor, as CEO in 2017. Vitale had her supporters, and was fiercely loyal to those she considered her own team — like chief merchandising officer Jennifer Sunwoo, who one characterized as Vitale’s “bad cop” — but both women could be very hard on staff. Former employees spoke of a leadership culture that favored falling in line, even as position after position turned over. One former salesperson described buyers, who sourced products for particular sections and categories, as scared of their bosses. (Reviews from former employees on Glassdoor are not known for their mildness, but on the site, only 35 percent of reviewers approved of Vitale. One especially piquant screed called her “an extraordinarily charismatic wolf in sheep’s clothing” and said that working at Barneys was a “dystopian horror show of fashion employment.”) At Gucci, Vitale had had to deal with Donald Trump, as Gucci’s store was in Trump Tower. Vitale liked to tell a story about how Trump liked her so much that when Ivanka was having a baby, he invited her to become a judge on The Apprentice because, as a former executive says she told it, quoting Trump, the show “needed another bitchy judge.”

Tomm Miller, the executive vice-president of marketing and communications at Barneys, disputed the characterizations of Vitale and Sunwoo. “Both women are highly regarded leaders who are long known to be collaborative, thoughtful, strong and supportive,” she said. “It is unfortunate that women in positions of leadership like Daniella and Jennifer are very often still subject to stereotyping that undermines strong leadership and track record of success.”

Investments were made online, and digital business grew significantly in recent years, but even in the age of e-commerce, focus remained on expensive-to-run flagships — including a much-publicized return downtown with a new Seventh Avenue store next door to the original Barneys. And unlike its competitors at Saks and Bergdorf Goodman, Barneys did not own its real estate, which left it in a precarious position. In August, following a lengthy dispute and arbitration with its landlord over a rent hike on the Madison Avenue flagship, eventually bringing its monthly bill close to $30 million, Barneys filed for Chapter 11, declaring more than $100 million in estimated debts (as well as more than $100 million in estimated assets). Its creditors included the Row, Celine, Yves Saint Laurent, and Balenciaga. Hamstrung by underperforming stores, Barneys had been closing locations for years — Dallas in 2013 and Scottsdale in 2016 — but it now announced it would close 15 of its 22 remaining locations and receive financing to keep the stores open while it sought a buyer for the company.

The race began to bail out Barneys. Rumors circulated, some that would previously have been beyond belief (could Steve Madden really be thinking of buying Barneys, as “Page Six” reported?), but by the bidding deadline on Wednesday, October 23, two potential buyers had emerged. One was Authentic Brands Group, together with the investment firm B. Riley Financial, which offered $271.4 million for Barneys’ intellectual property, which ABG would control, and its other assets, which B. Riley would. Their plan would reportedly close some or most of Barneys’s stores and license its IP to Saks Fifth Avenue, which would allow the Barneys name and brand to live on in some form in Saks stores.

Saks, which has reported quarter-on-quarter gains in comparable sales for nine quarters running, has spent several years pushing in a more fashion-forward direction and represents a lifeline for Barneys; but even so, many longtime Barney sites found the idea of Barneys domesticated into a pet project of the larger, more commercial Fifth Avenue doyenne dissonant at best. “It’s absolutely insane,” said Neil Kraft, who oversaw Barneys’ in-house advertising agency in the 1980s.

On the other side is a group of investors led by Ben-Avraham, the Israeli entrepreneur who founded the now-shuttered Atrium stores, was the first investor in Kith, and currently owns and operates trade shows. (His backers include his brother, Uzi Ben Abraham, of the real-estate company Premier Equities and the co-founder of the Scoop boutiques; Khajak Keledjian, the founder of Intermix; the fashion investor Andrew Rosen; and Ron Burkle, whose Yucaipa Companies already has a stake in Barneys.) His is the emotional appeal, one bolstered by a “Save Barneys” campaign, that has lit up Instagram. An accompanying Save Barneys petition has so far pulled in almost 20,000 signatures.

“It’s my passion project,” said Ben-Avraham in an interview this week. “Everything I did for the past 26 years was inspired by this establishment.” Ben-Avraham declined to go into great specifics about his plan — it’s the “billion-dollar question,” he said with a laugh — but it includes keeping at least some of Barneys’ stores, including the one on Madison Avenue. He said that the relentless focus on its rent as the death blow in the media had been overstated. The real culprit, he said, was mismanagement and the expansion into secondary markets.

Eitan Braham, a representative for Ben-Avraham, declined on Thursday to disclose the details of the group’s initial bid but confirmed it had been submitted by the Wednesday deadline.

A third potential bidder, a group led by David Jackson, chairman of the Aspen- and Dubai-based luxury-investment firm Solitaire, told Women’s Wear Daily he was working on a bid with backers in the Middle East. According to Jackson, his group did not manage to submit a bid before the deadline but was still hoping to submit a late bid if possible.

In these uncertain days, disquiet reigns. A window campaign at the Madison store poked fun at its plight and proclaimed Barneys “Not Closed,” but the staff was enduring “sleepless nights,” as the necktied associate who helped me slip on the $1,350 Japanese sportcoat by Ring Jacket I tried on told me (not on sale). Another spoke of polishing up his résumé after years and years in one place. It cannot have been good for morale to see Mark Strausman, the chef of Fred’s, the power-lunch spot on the Madison Avenue location’s ninth floor, escorted out of the kitchen by security on Monday, following an unflattering interview given to the New York Post. (“We hear that Strausman shouted, ‘Sayonara! I’m out of here!’” “Page Six” said.) “His contract was terminated after he made disparaging and unprofessional comments about Barneys,” Miller said.

Barneys has bounced back before. Within the store, Ben-Avraham’s bid has the broader support; the “Save Barneys” ethos, and the dangled return to a prelapsarian innocence, resonates. But some in the industry wonder if a plan without the benefit of an entirely new approach is more than a fantasy. And ABG and Saks, too, feel that they want to honor the Barneys spirit and let it live on.

From the old guard, Kraft, for one, was not terribly sanguine about the future prospects of a reanimated Barneys. He remembered, in the old days, being taken on a tour of downtown Manhattan to see where the old 19th-century department stores had been (Macy’s, before Herald Square, was at Sixth Avenue between 13th and 14th Streets). Most of the names, he said, were totally unfamiliar. “Three-quarters of them you’d never heard from again,” he said. “They all became dinosaurs.”

Thus might go Barneys the dinosaur. “I think people are trying to save a dream that was amazing at one point but that’s not valid anymore,” he said. “I want it to be valid because I want to live in that world. But it’s not.”

*This article appears in the October 28, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!