This wasn’t how it was supposed to go.

Not based on the electoral previews, anyway: the 2017 special elections and 2018 midterms that created the biggest blue wave Democrats have seen since the Nixon administration. These last election cycles were powered by young, first-time candidates — a record number of them women, many women of color, several of them with left-leaning political agendas. They ran on fury — at Trump, at sexual harassment, at a broken criminal-justice system, and at environmental collapse hastened by Republicans and the corporate interests they serve. These candidates beat not only incumbent Republicans, flipping house seats, but they also beat, or came very close to beating, some moderate Democrats — older white men who’d been in power for decades — in primary races.

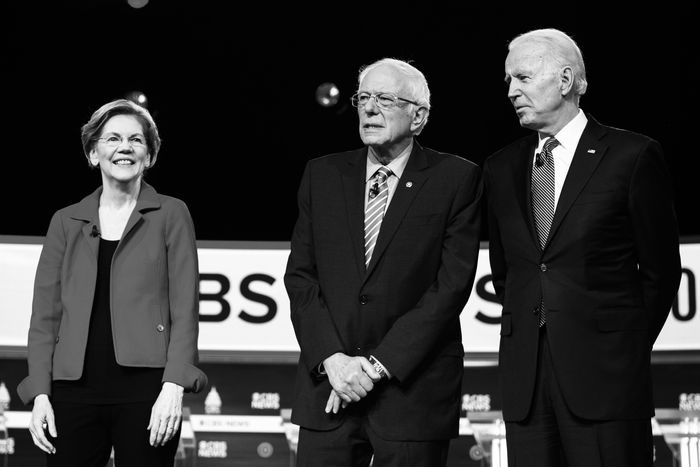

It was easy to imagine that in 2020, this push to usher in a new generation of leadership would hit a crescendo with a Democratic primary field full of new kinds of candidates: There were six women, some of whom had ripped into bankers, fought furiously against sexual assault and harassment, and openly challenged Brett Kavanaugh during his nominating process. There were candidates of color who pushed serious reforms to our criminal-justice system, advocated for crucial immigration reform, and argued for a universal basic income. There was a Jewish democratic socialist who had led the impassioned drive for Medicare for All, and one openly gay candidate who — before he began to court big donors and became a centrist — was talking about reforming the courts. Lots of the Democratic candidates were under 50, two were under 40; a few were very left, and the bulk of them were farther left than the Democratic Party had been for a long while.

And now it’s pretty much over, and voters have chosen a 77-year-old white male moderate who wrote the 1994 crime bill.

To some degree, Biden’s revival and now near-certain victory should be no surprise. The former vice-president has been leading national polling for almost all of the past year.

In a time of trauma and fear, which the Trump administration has been for millions, many voters, especially those in vulnerable communities, crave leadership they see as the safest bet for a more secure future. Writing about the southern black voters who cemented Joe Biden’s near clinching of the nomination, the New York Times’ Mara Gay described Americans who have already lived “under violent, anti-democratic governments” and “see in President Trump and his supporters the same hostility and zeal for authoritarianism that marked life under Jim Crow.” These voters, Gay reports, were worried that a democratic socialist could not win against Trump. And while many of them liked Elizabeth Warren, they were skeptical, following Hillary Clinton’s 2016 loss, that Americans would elect a woman. In Biden, a candidate they had seen in power before, they saw comfort and familiarity.

Other voters, including from rural white communities where Bernie Sanders won in 2016 and lost in 2020, suggest that perhaps it was antipathy toward his former rival, Clinton, and not a defining enthusiasm for Sanders’s left platform, that drove his support in 2016. Exit polls, though, show widespread support for policies backed by Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, including Medicare for All, even from those who didn’t vote for either of those candidates, suggesting that while the ideas they espouse may be popular, the depiction of the most liberal candidates as risky or radical bets hurt them more than the popularity of their policies might help them.

It was a field in which a centrist candidate could have been Kamala Harris or Cory Booker, and a progressive candidate could have been Elizabeth Warren or Julián Castro. And yet in the end, it was down to Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders, two extremely different politicians (one of them, the leftist Jew, an unprecedented first). But this particular winnowing reflects a lot about a nation in which all presidents have been men, all but one have been white, and in which the current executive-in-chief was propelled into office on a platform of xenophobia, racism, and misogyny. White masculinity remains a norm toward which many are trained to revert.

The need to pick the most reliable candidate, one that voters could imagine unseating Trump, has been stoked by a news industry obsessed with this president since before he won office. The same industry, and the Democratic Party itself, has spent the past year affirming the (questionable) view of Biden as the sturdiest vessel for Democratic hopes, even in the wake of midterm elections that suggested other models could succeed in the Trump era.

But those tasked with telling the story of American politics bore down on this diverse field; candidates were weighed, again and again, based on a notion of “electability” that in 2020 came to work as a kind of code word for racism, sexism, and an aversion to disruptive politics of the left. It meant that, again, institutional media had some influence over the outcome. That influence may have worked against those kinds of candidates who were firsts, who were breaks from America’s past.

During the midterms, for reasons both logistical (there are simply too many congressional races) and dubious (lots of national news pundits did not take the candidacies of so many women, especially young and progressive women, very seriously; Morning Joe’s former correspondent Mark Halperin once joked condescendingly about all the women who, after the Women’s March, were going to “run for school board down the road”), the historic wave of 2018 candidates didn’t garner a lot of individual scrutiny. Recall that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s primary challenge to incumbent Democrat Joe Crowley was taken so unseriously that she was not even credibly covered by her hometown newspaper, the New York Times, before she beat him and became one of the Democratic Party’s most electrifying and transformative figures.

But while there were certainly pieces of mainstream journalism pointing out the challenges these candidates faced — fundraising obstacles, the fact that many were facing big primary fields, incumbent candidates who are hard to unseat, and widespread doubt that so many women could win — there was no punishing national political spotlight trained on any one of them, magnifying those anxieties and doubts to the level of self-fulfilling prophecy. Ironically, it was perhaps because the notion of them winning in any mass numbers remained so far-fetched that there were not blaring headlines advertising those doubts, and thus prompting voters to be nervous about backing them.

Without the dire, widespread, suffocating forecasts of their doom, the 2018 midterm candidates didn’t have to maneuver around defining media narratives about their electability or likability; they campaigned in their districts, talked to voters, got covered by local media on the issues, and a historic number of them won.

In the 2020 presidential primary, there was no such room to maneuver, not with a cable-news machine obsessively covering the race for more than a year before the first votes were cast, and reflecting so much of an Establishment’s weird attitudes about female leadership that many preferred to pine for fantasy candidacies of women who might run for president — Oprah! Michelle Obama! — than to treat the ones who were actually on the ballot with optimistic respect.

The press covered every story about “electability”; every acknowledgment that, no, a woman has never won the presidency, that there is therefore no precedent for how one might do so, and that, yes, Hillary had lost and, yes, gender played a role (though not the only role!). After a 2016 race in which it was very hard to get people to acknowledge any role played by sexism, there was perhaps an overcorrection in 2020 — the presentation of sexism as so big a factor as to be insurmountable, a reason why perhaps it would be ill-advised to take a chance on a woman again; even feminists were nervous!

Lots of the coverage of these questions were historically grounded and smart; a lot of it was rooted in genuine concern: concern that America’s grim and narrow history of representation shows that only a candidate like Joe Biden, comfortable in a way that a moderate white men who had literally held office for more than four decades could be comfortable, could win.

It didn’t help that the Democratic Party Establishment and the press covering it showed again and again why feminists might be worried: The women in the race were often treated as rude interlopers, and backstabbing liars, often held to different standards than their peers.

After Harris challenged Biden on busing in a June debate, Politico ran a story in which Biden himself spoke of his shock that she would violate the interpersonal niceties of back-scratching politics: “I wasn’t prepared for the person coming at me the way she [did]. She knew [his late son] Beau, she knows me.” The story quoted Biden ally and longtime Democratic official Dick Harpootlian calling Harris’s critique of Biden’s record, “not right” and “distressing”: “It shows a lack of integrity: win at any cost … Why is she taking that shot when Joe Biden and his son did everything they could to help her?” The challenge to an Establishment — to the guy who’d been in power for so long that he imagined himself a benefactor of everyone who gained power after him — was cast as an ungrateful and unpleasant affront.

Warren, meanwhile, was treated as an unreliable narrator, grilled about her story of pregnancy discrimination, while Biden ran around telling stories about how he’d once delivered the One Ring to Mount Doom, but major media didn’t seem to care too much about his stretches of truth. The press highlighted Warren’s (very real!) difficulty drawing the support of black voters, while celebrating Pete Buttigieg, who polled at zero with African-Americans, as the next Obama.

The mass media didn’t just hurt the women candidates by casting them as shifty harpies; they also simply clearly held dear the notion that Biden was a norm to which many voters instinctively might want to return. Never mind that that norm was never a particularly inspiring one — in three presidential runs, Biden had not won a single primary contest before South Carolina — and that at 77, he was showing obvious signs of wear; his familiarity was a balm to those who’d spent decades covering him, as much as they imagined (perhaps correctly) that it was to voters.

There was a steady drumbeat proclaiming that Biden — who struggled in almost every debate — had had his best night yet. The drive to cast him as a hero, whatever his weaknesses as a candidate were, was high: “You’ve been an underdog pretty much your whole career,” CNN’s Chris Cuomo told him, cementing the view of the most powerful person to enter the race — the one who had already been vice-president; who had been a senator since the early 1970s; who’d written legislation that had harmed vulnerable communities; and who, even in this small context, had led polls since entering the race — as the least powerful. “You’ve achieved amazing things.”

When Biden brayed about his ability to physically best the current president, he was congratulated by some cable-news pundits, including MSNBC’s Donny Deutsch who said that he loved the idea of Biden on a stage next to Trump: “I love his height. I love that he threatened to get into a fistfight with Trump.” The same pundit worried that Warren lacked the “stronger strength” to go head-to-head with Trump, and forecast that she would lose 48 states were she the general-election candidate.

There are many plausible theories, and probably many actual reasons, that Warren, whose surge built slowly over the summer and crested in the early fall, when she became the first candidate to beat Biden in national polling, faded sharply in November. Lots of people believe it was her ill-advised decision to do the math on Medicare for All, a policy she supported but which was Bernie Sanders’s animating force, not hers (hers was an anti-corruption platform).

But what also happened in early November was the New York Times’ publication of its Siena Battleground State polling. A year before the election, the polls focused on head-to-head matchups between the three leading Democrats versus Trump, and found Biden to be the only candidate consistently leading the president, with Sanders coming after.

Polling is a valuable tool for candidates and campaigns; the Times-Siena poll offered a bracing view of how much work Democrats had ahead of them. But it was splashed over the front page of the paper; the Times published multiple news stories based on this one set of numbers, many of which included broad margins of error and were performed in states months away from a primary campaign that would acquaint them with candidates they weren’t already familiar with. The polling was treated in a way that begins to shape opinions, not just capture them. Again, in a time of national crisis, it is not irrational to attempt to divine a course toward something closer to safety. But the polls themselves were helping to create the sense of what and who was safe.

That impulse to feel secure surely led voters to make strategic choices over ideological or gut preferences, thus cementing that the impossibilities of the past might be replicated once again. In the days leading to Super Tuesday, people were tweeting out their intentions, or pleading with other voters, to throw over the candidates they preferred in favor of the ones most likely to win. Nate Silver, whose own modeling was the basis for many of these game-theorists’ choices, noted that “people may be underestimating the degree of tactical voting in this primary.”

The tactics weren’t just about media (and voters) coalescing around candidates who were familiar because of their gender and race and age, but also around those whose politics were comfortably familiar enough so as not to seem political at all.

In a November Guardian profile, New York Times editor Dean Baquet was described as having warned his younger staffers against embracing Warren or Sanders: “They [his staffers] probably want a more political New York Times than I’m willing to give them.” Baquet was surely trying to make a point about how he doesn’t want his staff to support any politician, but in singling out Warren and Sanders, and his young employee’s support for them, and calling that particular strain of sympathy “political,” the message he was conveying was that one kind of ideology is politicized in way that we should be wary of (the left kind), and at the same time not-so-subtly suggesting that the only people who embrace it are immature: “I hope they will learn over time that a New York Times that plays it straight has much more power and much more longevity.”

The Times editorial board wound up endorsing Warren, but it was telling that it did so via an unprecedented double endorsement; though the favor of the pick clearly went to Warren, a more moderate female alternative, Amy Klobuchar, was thrown in — as a little treat.

In the final weeks of the race before South Carolina, when Bernie Sanders looked to be in the lead, he was compared to the Nazi invasion of France by Chris Matthews on MSNBC, and to the coronavirus by CNN’s Michael Smerconish, who asked whether “anything can stop” either. Bernie was taken to task for his multiple houses (including one very lovely but definitely not yuge cabin on a lake) while commentators marveled at billionaire Bloomberg’s magical ability to enter a race and immediately poll so high, without ever having appeared in any debates. Both Sanders and Warren experienced periods during which their names were omitted from headlines, their images not shown (or in some cases, replaced with images of other candidates), leading viewers to imagine, even unconsciously, that they were not serious contenders. And in October, when it was Warren ahead, MSNBC’s Joe Scarborough struck at her commitment to left-wing politics. “There is not enough money for a country that’s $23 trillion in debt to pay for one-tenth of what she’s proposing,” he said.

This is what it means to have an Establishment really bear down on a contest, bringing the full weight of its media, its institutions, and its party. But Establishment thinking — which often includes sexism, racism, and anti-left bias — doesn’t just operate in opposition to any would-be interlopers or disruptors. It also gets those interlopers to replicate its attitudes and aim them at each other. A primary race is the perfect place to perform this trick, since support for competing candidates naturally turns partisan and ideological allies against each other.

So there were the Chapo Trap House guys tearing into Warren, and Jacobin writers seeding doubt about her having been a public-school teacher or experienced pregnancy discrimination, while the National Organization for Women proclaimed last week that Sanders had done “next to nothing for women” (despite a robust history of advocating for them). Warren supporters began to see a left that leveraged racism and sexism in order to find common ground with right-wing resentments and cast feminism and the desire for a progressive female president as fundamentally conservative; some Bernie supporters began to see feminism, and the focus on a female candidate, standing in opposition to their preferred candidate, as being more concerned with individual advancement than the success of a left-wing campaign that could deliver policies that would be better for all women.

This is how Establishment maintains its grip: left feminists vilify feminism, and feminist leftists vilify leftism, and everyone is doing the work of the white capitalist patriarchy, and neither CNN nor the DNC has to lift a finger.

The presidency — with its singular story line and its cult-of-personality focus on individual candidates instead of their ideas or policies, and the billions of dollars to be made by wall-to-wall coverage of it — remains the hardest nut to crack when it comes to electing groundbreaking candidates.

But that doesn’t mean that the lessons and outcomes of 2018, versus 2020, are lost to those who are still committed with every fiber of their being to changing who has power and to what ends they use it. Because the good news, for the rest of this year anyway, is that the presidential race is still happening, and much mainstream energy will continue to be devoted to covering the battle between Donald Trump and Joe Biden. And those whose political drive takes them in other directions can return to the work of pouring energy into the down-ballot races that will probably not draw the focused political acuity of Donny Deutsch. And that is, in the long run, even more crucial to what happens next than the question of who’s in the White House.

Already there are signs that the insurgent energies of 2018 still exist in races outside the presidency. Twenty-six-year-old Jessica Cisneros didn’t beat the incumbent conservative Democratic Representative Henry Cuellar in Texas, but as a young first-time candidate, she came incredibly close with 48 percent of the vote; she can run against him again in two years. Like Marie Newman, who in 2018 came so close to unseating longtime incumbent and odiously conservative Democrat Dan Lipinski in Illinois; their primary rematch is next week. Cori Bush, the progressive Missouri candidate and registered nurse who challenged incumbent Representative William Lacy Clay and lost in ’18 is on the ballot against him again in August.

Outside the 2020 presidential race, and looking ahead to 2022 and 2024, the push to alter who has power has not even paused.