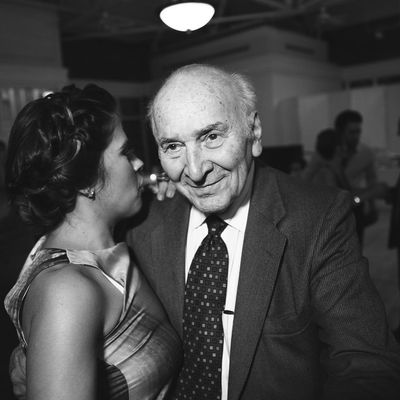

My cousin Jacob Solome, or Jack, will only tell me how old he is; for the purposes of this article, he says, “Put me down in the high 90s.” He met his wife, Eda, now 99 and suffering from dementia, when they spent two years hiding from the Nazis in a Polish farmhouse, crawling under floorboards whenever they heard anyone coming. They’ve been married for 75 years. A retired obstetrician-gynecologist and news junkie, he’s long kept a full schedule of teaching, swimming, and driving like a drag racer to various social engagements. Pre-pandemic, we would meet at his favorite all-you-can-eat Pan-Asian buffet in Sheepshead Bay, not far from the Midwood home where he and Eda have lived for a half-century. Now, with each of us in isolation, I called him up to see how he was doing and to get his advice on what it takes to survive a disaster.

Irin: What’s been a typical day lately?

Jack: We have a routine with Eda. I have aides helping me. At the present time, we need two people to get her up, so I’m the second person. Taking care of my wife is my primary job at this point. I’m really happy that I’m able to do it.

Irin: Are you bored?

Jack: Somewhat. I can go out for a walk, but I don’t know if I should go shopping because I’m afraid. I have Disney+, Netflix, and Verizon, so I look at interesting stuff: some historical, some detective stories.

Irin: How long were you in hiding in those years in the war?

Jack: I think about two years, and this was when the war started.

Irin: How old were you?

Jack: Fifteen.

Irin: Did you go outside at all?

Jack: We didn’t go out because we couldn’t. It was a farmer who was hiding us. He had built something under the floor, where the moments we felt there was somebody coming from the outside we would hide. There was always somebody at the window watching. At times, we were 15 people in the small hole there; if they would find us, they would shoot all of us. We had situations like that for the whole two years.

Irin: You didn’t have Netflix and Disney+ in that Polish farmhouse, did you?

Jack: No, we did not have that. But it was not boring because we were always on watch.

Irin: Fifteen people in how big of a space?

Jack: It’s like being in a very tiny basement.

Irin: So you wouldn’t compare it to what we’re doing now?

Jack: What we are doing now is a luxury.

Irin: That’s where you met Eda?

Jack: Yeah. When the Germans came to Lithuania, she started walking from Lithuania to Poland, to the border. [That was] probably about 50 kilometers. She was walking day and night and arrived in her cousin’s village, which was called Orany. And then all the people had to run again, so she ran to another community, and from that community, she ran, and then she had to leave again, and she wound up coming to the place where we were hiding. It was really another miracle.

Irin: I don’t actually know how you guys got out of there. What was the day that it was over?

Jack: For us it was over in 1943, when the Soviets came. We heard them coming, we heard shooting — not only low caliber but the big guns — so we knew that they were here. So we waited a few days, and we walked out, and the farmers told us the Soviets are here. Don’t forget, we were in the ghetto for a long time before that.

Irin: Do those memories come back to you?

Jack: They do come back in a different form because I lost two brothers before we went into hiding. At the beginning, when the Germans came to Vilna, before the ghetto, the Germans went and they caught all the Jewish people, including my brother, and they took him to a place which was called Ponary and shot them. [As many as 100,000 Jews, Poles, and Russians were killed in the massacre.] The other brother we sent to my grandparents in Lubcz. We thought it was safe because it was so far east, but the Germans came there and they killed them all. My brothers and my grandparents; that comes to my mind quite often.

Irin: Was it hard to go on after that?

Jack: That’s what I told you: You have to be a philosopher. You have to put things out of your mind, not to think about bad things all the time. You always look ahead … I’m preaching to you.

Irin: I want you to preach to me. You’re optimistic, and I wonder if it’s one of the qualities that helped you and Eda survive.

Jack: Absolutely. This is my philosophy, and so far it has helped. Because I compare myself to other people who worry all the time, and always when you see them, they are telling you about their tsuris and their problems. Some people are optimistic, but some people are more pessimistic. I am in the first category. Really, that’s the nature of a person. I’m always thinking how worse it was when we were under the German occupation, where every minute, our lives were at risk; literally, being in the ghetto and being in hiding. So if I was able to live through that, what the heck is coronavirus?

Irin: For me, being pregnant, I’m thinking about the future a lot. You’re also a gynecologist and obstetrician, so do you have any particular advice for me?

Jack: Try to move. I have a stationary bicycle in an extra room, and I do it a few times a day, and you should do that. You don’t have to always — when you feel tired, you sit down. But you take your vitamins, you eat what you’re supposed to, and subject to the unforeseen, you’ll do great.

Irin: Thank you. Is there anything that we can do during this time for you?

Jack: I don’t know if you’re a believer, but you should pray. Pray that the coronavirus should disappear and then we’ll be the way we were. I have no choice. I have to stay alive. I have a function.

Irin: You mean take care of Eda?

Jack: Yeah. It’s all because of her.

*This article appears in the March 30, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!