The Cut is publishing excerpts of books coming out during the coronavirus pandemic. After each selection, join us for brief interviews with the author.

Outside the bar, near the dumpster, smelling of booze and damp with rain, morning deigns to greet me. The little boy’s face hovers over mine, blocking the sun like a low-flying cloud.

“Would you like to talk to me,” he asks, “instead of talking to yourself?”

He can’t be more than seven years old. “Sure,” I say. “Hi.” “What do you do here?” he asks. “I look for jobs.” He doesn’t laugh at me, but nods in a serious way. He offers a hand so I can sit myself upright.

“I have a temporary job for you,” he says. “I’ll pay you money.” I agree to follow him to his home, and to perform the job of being his mother. I throw my cigarettes in the trash, finally unlearning that old, temporary skill. He leads me down the alley and through the copse of trees, past the prison, deep into the forest, to a clearing, to a strip of stores abutting a stream. Somewhere along the way we cross the street, and I realize he’s holding my hand.

There’s no one else in his apartment, and the building looks all but abandoned. The sounds in the hallways have no bodies to catch them, muffle them, and they ricochet forever, lost bullets. The pitter of a mouse, the patter of shifting beams, horsehair walls wall-papered on an inconsistent slant. In one corner rests a kitchen, and in another corner a couch. A rug with one corner turned up and over, revealing hidden colonies of dust.

“Here, have a seat,” he says. He points to the floor, resetting the corner of the rug with his toe. We sit across from each other.

“Where’s your real mother?” I ask. “Abducted by pirates. But she’ll be home soon.” I remember Darla ripping the cap off a bottle of cider with her teeth, and I stay silent. The captives in the dungeon, the inventory in the hull.

A kitten crawls from under the couch and nestles in the boy’s lap.

“Do pirates like cats?” he asks, his voice shaking. “There’s no purr in pirate,” I say. “Never fear.” The cat curls against his chest and stays put when the boy stands, its claws cutting into his shirt.

“Wear this,” he says to me, and he hands me her apron, her slippers, her shirtdress, her vest, her leather jacket, her Halloween costumes, her skinny jeans, her nightgown, her shower cap.

“Your real mom was pretty cool.” “Is.” We sit and do his homework on the floor until he’s tired, his cheek slipping from the cup of his hand.

“Well, I’m spent,” he says, and he shuffles to bed like someone older. “Make yourself at home.”

The boy does exactly what he said he would, which is pay me to cook and clean and give him advice and tell him a different story every night. Sometimes I’m supposed to scold him or punish him, and sometimes I’m supposed to yell for no reason, get sad, and stare out the window.

“Like this?” I ask, leaning my forehead against the glass. “More desperate,” he says, studying my gaze. “Pick a point of focus outside and commit.”

I commit to a flowerpot across the street. “Now pick something just beyond the flowerpot, something only you can see.”

I settle on a long, lithe creature of the forest, a predator from my imagination.

“Much better,” he says. “You look real sad.” “Thanks,” I say, smiling. He rolls his eyes. “Stay in character!” I cut his hair and watch him brush his teeth and lift him high so he can spit in the sink. I lift him on my shoulders and spin him around the room. I buy the groceries and cook the groceries, dividing them from their bundles and bunches and loaves, slicing and stirring and whisking, building flavor profiles, concealing vegetables, chopping at pleasing angles to create from the crusts on his plate a face with a smile. Supplying nutrients for growing boys. Tupperwared leftovers filling the fridge.

I tell him the story of how to bake a pie. I tell him the story of the daily news. I tell him the story of how he was born, which he has to tell me first.

“It was a dark and stormy night,” he explains, snug under his sheets.

“Really?” “Yes, really. Sometimes it really is.” “It was a dark and stormy night,” I repeat, and he settles into my retelling.

I tell him stories about the jobs I’ve had, and even the boring stories make him squirm and scream. I pick the boredom until it bleeds. I don’t tell him the stories are true.

“Tell me the stories, tell me the stories,” he says, clapping his hands against his knees.

“Okay,” I say, and I take a sip of water. These are stories I know well, but sometimes a mother needs a minute. “Once upon a time, there was the assassin. There was the child.”

“What else?” “There was the house with the doors that opened and closed.” His eyes start to widen, then flutter, then droop. “There were bombs and blimps and barnacles, and a little boy who was best of all things.”

I walk out of his room backward, watching him sleep. “The box of stamps and the corkboard calendar and the pink book of message sheets to tell you what happened exactly, specifically, in detail, While You Were Out.”

“Leave the light on in the hall,” he calls after me, and I do.

The boy is pale as potatoes and skinnier than the women at the agency, which is really saying something. So I perform some extra work that he wouldn’t know to ask about. Like researching vitamins and malnutrition and dietary supplements. I use the money he pays me to buy medicine from the man at the bar, and my little boy’s cheeks turn pink again, if they were ever pink to begin with. I remember the time I almost had an accidental little boy of my own.

“Why are you using your salary for my medicine?” He kneels in his chair so that we’re the same height.

“Because I care about you, and you’re sick.” “You’re not supposed to care about me. That’s not your responsibility.”

“Actually, it is,” I say. “I promised you a job, not a family,” he says, a baby snarl dilapidating the base of his chin. He’s already growing up cruel, I think, brokenhearted, primed to break hearts. I wonder if he’ll grow up to be someone’s boyfriend, their only boyfriend, or one of many.

Someone’s father. Father of many. Someone’s pal. Someone else’s kid. Then I remember his mother, the pirates, Darla. I crush the vitamins and hide them in his food.

“I thought I made myself clear,” he says later, spooning the evidence onto a saucer. Mashed squash pebbled with pills.

“You’re right,” I say. “I’m sorry,” and finally he smiles. He dangles a string for his cat to catch, and the cat is pleased to catch it.

The boy tells me about his ten-year plan, about how he wants to run a business when he grows up, how he could run a business very fairly. A business he could pass on to his kids, something that would stick. “First you need a prospectus, like this,” he says, drawing a circle with his finger on the kitchen counter. “Then you start hiring,” he adds, “like how I hired you.”

“You hired me next to a dumpster,” I say. “You’ve got to start somewhere.”

The boy’s plan sounds bright and metallic, so sleek that it hurts to look in the direction of his dreams.

“In that case, can I have a job at your company?” I ask. “Of course,” he says, “pending approval of your application.” We go to the store and pick out the right kind of pens for his company, the kind a real businessman might use. We click them open and test them on papers filled with scratch. He carries them home, bag swinging around his wrist. Then he lines them up on the desk next to his bed. We do homework and dot the i’s and cross the t’s like honest professionals.

I notice that when I say certain unfamiliar words, he repeats them later in conversation, mispronouncing them, which makes my heart feel larger than ever before. He grows and grows and grows.

When he finds out about the Chairman, he thinks I have a super-power. “Can I see him? Can you tell him to appear?” he marvels.

“Oh, he comes and goes as he pleases.” “But who tells him to go away?” “No one. He never goes away.” He pretends to talk with the Chairman in his room, down the hall, and into the kitchen. I can hear him exclaiming and reasoning, discussing everything from math homework to pets.

“Whoa,” he says, collapsing on the ground. “Whoa, the Chairman is so cool!”

“Whoa!” I say. “Did you see him? He was hanging out with me!” “I totally saw.” “Whoa.” When I’m up late, walking about in his mother’s slippers, my necklace starts to burn, and the Chairman keeps me company watching late night television talk shows.

“Did I miss him again?” the boy asks in the morning. “Your sweater is too small,” I say, and we go shopping for a new one, with a zipper and patches and pockets to hold the treasures that come with being a kid. Then he’s too big for the new sweater, and we shop for a newer one. His parade of sweaters could stretch around the apartment and over the cat and under the rug.

I sign permission slips, practicing the forgery for field trips and class projects. Yes, my boy can travel to the clock tower. Yes, my boy can dissect a frog. And also, yes, he may. After school, he runs down to the stream with other boys his age. One of them wears a helmet, because he has a new bike. They share the bike and throw away the helmet. They take turns. They all pile on at once, like bees on a hive, and the bike falls flat on its side.

I save my money and I buy him a bike of his own. “You really need to stop doing this,” he says, shaking his head, disappointed that I still don’t seem to understand.

I shrug. “I can’t help it.” “Try,” he says, grabbing the bicycle handles, the bright red bell above the brake. His face changes for a minute, softens. “I’ll keep it,” he says, “but only to make you happy.”

“Fine,” I say, and I smile to myself for weeks. “Don’t mention it,” he says, and he rides his bike into the sunset like the cowboy I’ve raised him to be.

The other mothers gather at a picnic table for coffee, and I join them.

“Whose mom are you again?” one of them asks. She has a short blond bob that leaves her neck long and free.

I point to the boy who is mine. “Did you get your nose done?” they ask. “Did you gain some weight?” “Did you dye your hair?” Not remembering but somewhere deep down suspecting, suggesting, I’m not the person I pretend to be.

“Yes,” I say, to all their questions. “All those things, yes.” “That explains it!” says the blond bob. She offers me a cracker and some cheese. She offers me a glass of wine, later, on her couch.

“The kids!” they exclaim, and they talk about their kids. “The pets!” they exclaim, and they talk about their pets. “The husbands!” they exclaim, and they talk about their husbands. The plurality of their lives, I think, trying to cast a line to a person, place, or thing I can claim for myself.

“What about you?” asks a mother with adult braces. “What about me?” I ask, genuinely wanting an answer. No one answers. We read magazines and the glass of wine in my hand refills itself thanks to the magical properties of women gathered in a room. We volunteer to chaperone a school dance. The boys stand around a box of donuts, watching its contents with the intensity of attempted levitation. We stand near the door, guarding the comings and goings of our children, our cheeks flushed with the cold.

“Why not a slow dance?” says the blond bob, and she changes the music. Now the boy and his friends are holding the donut box, all hands on deck, as if to say, We’re clearly busy with something else right now.

The girls coagulate in the darkest corner of the room. “I love this song,” says the blonde bob. She dances with another mom.

I look down and my boy is standing by my side. He touches my wrist.

“These pants are all wrong,” he says. “What’s wrong with them?” “Everything,” he says, almost crying. I walk back to our apartment and retrieve a pair of khakis. I walk back in the dark, khakis slung over my shoulder like a pelt for his survival.

“Thanks,” he says, running off to change in the bathroom. He tucks his wrong jeans in my bag and returns to his friends, to their deliberations over donuts.

“Wasn’t that fun?” I ask him on our way home at the end of the night.

“It was a kind of fun,” he says. We walk the rest of the way in silence. When we get home, he suggests I get mad, then get sad, then stare out the window.

“That’s how it should be,” he explains, walking off to bed.

The moms sit at the picnic table with their coffees. We talk about the boys. We talk about the bombs. We talk about the petition for the thing no one remembers. We bake cookies and bring them to bake sales and sell the cookies for more than they’re worth.

“I feel so undervalued,” says the blond bob. We go for walks sometimes in the afternoon. She starts to sob. “Do you value me?” she asks.

“Of course,” I say, patting her round, bright skull. Like polishing a prize.

We walk to the stream and take our shoes off and put our feet in the water. It feels cool and fresh between our toes, and then it feels like nothing. We wade until we’re numb, continents of snow drifting over the tops of our feet.

“And at what cost,” she asks, a question in a conversation we’ve never had.

My boy leaves his keys in the door and gives me a fright. Is he old enough to drive? I can’t remember.

He and his friends go on a field trip and learn how to craft artisan paninis. They come over and demonstrate their new skill. They make one just for me, with thick bread and the nicest cheese you can buy at the store, with aioli and fresh tomatoes and ribbons of basil, and it’s simply the very best thing I’ve ever tasted.

“It’s the very best thing I’ve ever tasted,” I tell them. “Hooray!” “In my whole life.” I scoop shiny spheres of ice cream for them, and they play board games on the floor, falling asleep with a milky lacquer over their lips. The old cat traipses through the casualties, knocking over piles of cards, swatting at the plastic pieces.

I stand to watch the scene, the boy and his friends scattered on the rug, heads almost touching, limbs landing this way and that. Tomorrow, I think, I’ll rent movies. They can watch movies all day long. They can just sit here and watch as many movies as they want. How many days are like that? It’s a good kind of day to have. I make a shopping list for all the different kinds of days I want to provide for my son, and I cross this day off the list.

The moon lights up the living room like a screen. I go to my room to get some sleep.

In the morning, I wake up already standing. I’m standing over the kitchen counter. The boy is standing across from me. When did he get so tall? Do I see the beginnings of a beard?

“You were sleepwalking,” he says. His friends stand behind him, providing some unclarified moral support. “Where did I go this time?” I laugh. “You went to collect your things,” he says, opening one hand and revealing my eye patch. “Pirates,” he murmurs to his friends, barely holding his voice in place.

“It’s not what you think. It’s a costume,” I explain, “for Halloween,” my heart already breaking. I try to lie every day, practicing mostly on myself.

“Is this a costume too?” he asks. In his other hand, he reveals the brooch in the shape of a nautilus shell. The same shape found in the nerves collecting behind his eye at this very moment. In his eye he collects a tear, then another. “This was my mother’s,” he says. “Why do you have it?”

“I don’t remember,” I say. I muster all my human resources to not collapse, to not die right here on the spot.

“Get out.” “No,” I say. His friends look at me, unfriendly friends. The old cat hisses. “Out,” he says, pointing to the door. “I’m sorry, but I can’t just leave you here alone.” I place my hands flat on the kitchen counter, which I have come to think of as my kitchen counter. My kitchen. My cat. My home. My child. “You’re just a child,” I say.

The light sort of shifts. Does he have a tattoo? A mustache? “I’ll call the police,” he says, and I know he means it. I know I won’t be as lucky a second time around, running from the law. “This transaction,” he says, “is not open to your interpretation.”

As I exit the apartment, I’m scolding him, punishing him, yelling for no reason, getting sad, and walking out the door. I thought my steadiness had nearly arrived, but here I am, alone again.

“Don’t come back, ever,” say his friends. There are lots of different kinds of mothers. He never specified which kind he wanted.

This is me, the type of mother who leaves. “Where you heading?” the blond bob yells in my direction. She’s standing at the corner. I don’t respond. “Hey! Where you going?” I keep walking. The artisan panini shop has been replaced by a bank. All the same bank. New stores. All the same stores. I don’t recognize a single thing, and I recognize everything. It’s exhausting. Once my heels were solid, but now they’re rotted through, the infrastructure of the stolen boots laid bare. I once walked along and sometimes skipped. Now I skip minutes, seconds, hours.

I find a job flipping burgers, and that’s all there is to that. I keep expecting the job to reveal itself in full, but not all jobs are icebergs, with hidden miles of work. Some jobs are just jobs. I tuck my hair into a net and conduct daily dealings with grease and fire. I catch my reflection in the sneeze guard, and she’s a stranger.

At the new bank, they’re hiring human metal detectors. I drink a thick milkshake filled with special particles, and now, when someone walks past me, I can detect their metal. I can also detect their mettle, an unintended side effect.

You explain to your supervisor that you can detect their despair, and your supervisor declares that this makes sense. “Despair clings to the metal you’re already detecting.”

We detectors have the simplest of intentions: to keep people out, to keep people in. To sense something extra, a sheath or a shroud, a holiday bonus, an elbowed bracket that extends past the boundaries of the body. The boundaries of the bank are high and tinseled with security cameras, electrified with wire, gilded with lights that lead me back to my place at the front entrance.

I detect some metal in the shape of a toy. I detect some metal in the shape of a nautilus shell. I detect some metal in the shape of a knife and look up. Laurette’s face looks back. The sorrow I detect is so deep and unbearable, I throw up. Seasickness, sorrowsickness.

When I collect myself, Laurette has disappeared, and my supervisor stands over my head.

“Pack your things, obviously.” Then it’s unemployment for months, for maybe one hundred years. Unemployment: Don’t say that word in front of the baby, my mother had scolded her mother. Such shame, the first time I have ever been without occupation. But time seeps in around shame’s edges. Unaccounted time, time without sheets or stamps or cards. Time introduces herself to me, to each of my empty hours. Time is a new acquaintance, and she does something funny to my limbs, my worries, my anger, my life. Garbage sidles up against the curb, like a lonely lover looking for affection. There is no one living in that building across the way. A tree lost half its branches yesterday, and everyone continues to walk through the ghost of its shade. Unaccounted time has its own inventory.

On a cold morning, I feel a lump in my throat that lasts all day. On a humid afternoon, I find a stray pamphlet tucked inside my boot, stinging the bottom of my foot for who knows how long. I hold the pamphlet to my chest until it burns like a rash. I make a wish on the pamphlet to go home. For a place to belong. I even click my broken heels together.

On a rainy evening, I wait at the dock, in the harbor, near the public beach.

On a foggy night, in the distance, a billowing sail, the silhouette of a vessel on the move. I run with everything I own, which is nothing, just my necklace, hot as fire, just me and the Chairman of the Board, racing to meet the pirates at the shore.

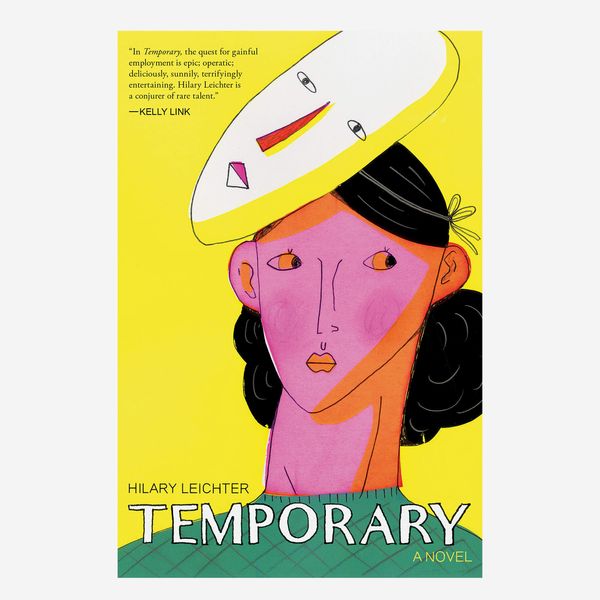

Used by permission from Temporary (Emily Books, Coffee House Press, 2020). Copyright © 2020 by Hilary Leichter.

Hilary Leichter’s debut novel, Temporary, follows a young woman as she performs a surreal string of jobs, from working on a pirate ship to apprenticing for an assassin to mothering a little boy who hires her. Kerensa Cadenas, the Cut’s senior culture editor, spoke with Leichter about the release of her novel, which came out on March 3.

Reading your novel felt like reading a fairy tale. Was that a deliberate choice?

I think that we look to fairy tales as adults differently than the way we look at them when we’re children. As an adult, I think the fairy tale can provide proof that the world is just incomprehensible. So it was important to me to create a fairy tale for the way that we profit off of and are corrupted by and injured by capitalism. I don’t know that that specific fairy tale exists, but I wanted to make a modern-day version of that.

There’s this quote I keep thinking about, that “it’s not personal, it’s just a job.” What were you trying to get at when you wrote that?

You hear all the time: “It’s not personal, it’s just business.” It was very important to me to invert that on the very first page. There’s nothing more personal than doing your job. When you go to a party, when you encounter anyone you haven’t met before, the first thing that you’re asked is what do you do? It’s the door that opens into who you are for everyone that you meet. I think the idea of what is personal and what isn’t is an interesting one. And who gets to decide what’s personal and what isn’t, and who gets to decide what we’re allowed to take personally and what we aren’t.

If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.