The Cut is publishing excerpts of books coming out during the coronavirus pandemic. Before each selection, join us for brief interviews with the author.

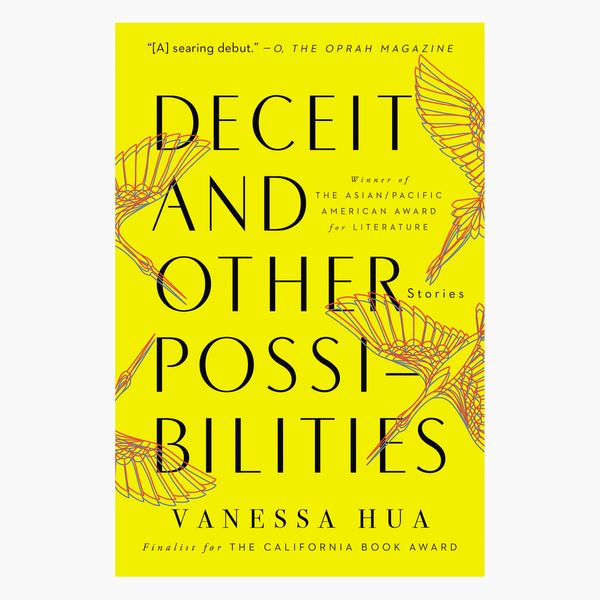

Journalist and novelist Vanessa Hua carefully chronicles the immigrant experience in her short-story collection Deceit and Other Possibilities, which follows people of Armenian, Mexican, Chinese, and Korean descent as they make lives for themselves in America. Kerensa Cadenas, the Cut’s senior culture editor, spoke with Hua about the reissue of her collection, which came out on March 10.

Your book is a reissue and you’ve added new stories to it. Has your writing process changed since it first came out?

I finished “Room at the Table” last year, but I think what’s interesting about that story is that I actually began it in college. I graduated in 1997, but this was a story that I just couldn’t figure out — I just couldn’t quit it. Looking back, this is a book that has spanned such a big chunk of my life. I feel very fortunate to revisit this collection and to add these three stories that reflect my ongoing interest in immigrant families and, in secrets and lies.

Why do you think you’re drawn to writing about the generational divides?

My parents were born during WWII. They moved from China and then they fled to Taiwan and then came here for grad school in the 1960s. They didn’t talk much about their past. So as an adult, I was able to ask for more stories and I got some of them, but my father passed away in 2012. There’s always that sadness about what has been lost and thinking about what all they gave up to come here, you know, their family, their culture, all of that. I think throughout the stories in my book there is this sense of wanting so much to connect but maybe falling short and that gap.

Grace had the urge to introduce herself again, though that would be insulting. They were family, but it had been years since she and her cousin Daniel had seen each other.

“The volcano erupted right before we landed in Manila,” he told her. With his spiky black hair, he appeared not much older than when they had roughhoused at family reunions, weddings, and funerals. “It was dark at noon.”

“We tied bandannas around our faces to breathe,” said his wife, Phyllis. After postings to Kenya, Thailand, and the Philippines, they had returned to the Bay Area to plant a church. They were also expecting. Their son, due next month, would be the first child of the next generation, the firstborn of the Americanborn.

Phyllis started coughing, and Daniel left to fetch a glass of water. Her cousin had become a stranger. Seeing him tonight, she realized how much she had missed him. On the radio, a commentator mentioned Saddam Hussein’s trial, and holidays for the troops in Iraq. Grace searched the dial for Christmas songs, and then dug into the bulging brown grocery sacks of decorations she’d fetched from the garage.

“What year are you in college?” Phyllis unfurled a gold garland.

Grace winced. Her attempt at adulthood — her bobbed haircut and tailored shirt and trousers from a Williamsburg boutique near her apartment — had failed. “I graduated eight years ago. Class of ’97.”

“I’m sorry, I should have known.” Phyllis brushed a strand of tinsel from her long black hair. Her hands were callused, imbued with a nimble flexibility. “I’m bad at remembering those things.” She rubbed the small of her back, shifting in her ballet flats to find a comfortable standing position. Her slight frame seemed too fragile to support her swollen belly.

“You’ve been away,” Grace said.

They’d left while the first Bush was president, and returned after his son came to office. They’d missed the Clintons, 9/11, MySpace, and other collective American experiences that had marked Grace’s own entry into adulthood. She untangled an ornament, a project from elementary school, a red clay stocking with her brother’s initials carved on the back in crooked letters. The first and only time she’d met Phyllis, at their wedding, Grace had still been in high school.

“You know the saying, ‘Asian don’t raisin’?” Grace said.

Phyllis laughed. “Still, though.”

“I’ll probably feel insulted once I stop getting carded,” Grace said.

It was Christmas Eve, and Grace’s father, as always, hosted dinner. The elders were in the kitchen, drinking tea. Grace called her father Baba when she was small and now when she was sentimental. He was First Uncle to her cousins, the elder of their extended family.

Indoctrinated from his college years in Indiana, Baba insisted on Western rituals for the holidays. Cranberry sauce with turkey, visiting church on Easter and Christmas, slices of canned pineapple on ham, and a fake Christmas tree — garnishes of propriety, of patriotism, as American as the stars and stripes, as the red, white, and blue.

Kneeling, Grace plugged in the Christmas lights, which reflected off the windows and winked onto their faces like a neon sign. As she stood up, Phyllis swayed and leaned on Grace’s shoulder. Startled, Grace stumbled before steadying them both.

Phyllis apologized. “Standing too long, I guess. Blood pools in my legs, and then I get dizzy.”

She didn’t mind bearing her cousin’s weight; it felt good to be sturdy. When Ma called them to dinner, Grace steered Phyllis to the dining room.

Baba sat at the head of the table, next to the turkey, and Ma at the foot. Phyllis and Grace joined Second Uncle, Baba’s widowed younger brother, and Daniel, already seated.

The table delighted Baba with its promise of expansive hospitality. Tonight, though, for only six guests, he didn’t need to pull out the extension. With her brother Frank missing, everything felt off-kilter.

At past family dinners, Baba had advised Daniel, and her cousin in turn asked questions of the family elder. They were both the first sons of their generation, and Daniel had once excelled in this role, winning scholarships to cover his schooling at UC Berkeley. Grace had envied her father’s interest in her cousin, paternalistic but given with the respect and knowledge that someday they would be equals. Upon graduating, though, Daniel became a missionary.

Now Baba asked him to say grace.

Daniel looked around the table. “Where’s Frank? Is he coming later?”

“Work,” Baba said a little too quickly.

Daniel couldn’t hide his surprise. “On Christmas Eve? Even my parents closed early tonight.” They ran a diner in Chicago.

“End of the year, he’s finishing a project,” Baba said.

Her cousin nodded. He looked down, seeming to collect himself. “Dear Father, thank you for blessing all of us this year. Let us thank First Uncle for having us over to share time with family. Thank you for this feast, and for bringing us safely together. Amen.”

The family repeated after him, “Amen.”

Baba carved the turkey, cutting the breast so that each snowy slice had a sliver of crispy skin. He speared a piece with the serving fork and offered it to Daniel. “You should use your education and write software. So many Chinese in tech. You can give money to the church and help out your parents. Use all your talents. A Godgiven gift.”

Daniel held Baba’s gaze. “The church is my calling.”

Grace wished his prayer could have brought a god through the ceiling and into their laps, that he could part the Red Sea or rain down frogs to demonstrate his powers to Baba — anything to prove that Daniel and their generation could succeed outside the decrees of their elders.

“Hao chi,” Second Uncle said. Tasty. Even before he’d started going deaf, he’d always been a beat behind the conversation. His wife had died of a heart attack five years ago. They’d never had children, and he now lived alone in senior housing in Oakland Chinatown.

Because Chinese respect dictated that aunts and uncles were to be addressed in terms of birth order, Grace did not know his real name, in English or in Chinese. Though younger than Baba, he’d aged twenty years since becoming a widower, and seemed a withered replica — quiet, pale, and wispy next to the hearty solidness of her father. His green argyle sweater looked familiar; it was a hand-me-down from Baba, she realized, one she’d picked out for him years ago.

When her cell phone vibrated in her pants pocket, Grace jumped in her seat. She checked the screen: Andy. New York was three hours ahead and she would lose her chance to talk to him if she waited to return the call. Excusing herself, she went into the kitchen.

“Merry Christmas,” Andy said.

“Happy Hanukkah,” she said. This year the holidays coincided.

Tomorrow he and the twin girls he shared with his ex would drive to Tenafly and spend the day with her, her new husband, and their baby on the first night of Hanukkah. Grace pictured him shirtless in his striped pajama bottoms, pushing his horn-rims with the tip of his finger, his curly dark hair flecked with silver — on his head, and on his chest. Right now snow was falling, she was sure of it. She read the forecast before she left: a 90 percent chance of snow showers, temperatures in the thirties. Just as she checked Bay Area weather every day while in New York, mindful of the family left behind, mindful of the life she might have led had she stayed: dinners home on Sunday nights, ferrying her parents to social events, responsibilities her brother had handled until he sank out of their lives.

She’d moved to New York after college to take a recruiting job, promising she’d go for one year that turned into two and now eight. Her parents had never stopped pressuring her to move home. “Henry and his wife bought a house in the neighborhood,” her mother would say, mentioning a high school classmate. Then she’d email Grace listings for starter condos. Her father sent news articles about stabbings and shootings in Queens, New Jersey, or anywhere else in a hundred-mile vicinity of her apartment.

They didn’t yet know her landlord was tripling her rent, and her roommates had found places elsewhere. Andy wanted her to move in.

The phone crackled. The reception was bad, and she leaned over the kitchen sink, tilting her phone toward the window. Water soaked the hem of her shirt, the damp fabric chafing her skin. The morning she flew out, they’d taken a shower together at his apartment and flooded the bathroom. She had almost missed her flight.

“We just started dinner,” she said.

“Put me on speaker, I can say hello,” he said pointedly.

She didn’t answer. She was thirty now, too old to be sneaking around, and not for the first time, her secrecy annoyed him.

She cleared her throat. “I should go. I’ll call you later.”As she hung up, she heard his tinny “I love you.”“I love you too,” she whispered in return, a moment too late. She wanted to rest her head against his chest, listening to his heartbeat. Reach up and stroke the scruff on his cheeks and on the back of his neck. He was fifteen years older and divorced with children, not anyone her parents might accept: a son of Chinese immigrants who attended a top university, who worked in a respectable profession of medicine, engineering, or law. If she married him someday, it would blow up what remained of her family.

Half a year ago, her brother had proposed to Gabriela, and moved in with her and her son, a kindergartner. He’d said nothing to Baba and Ma until he knew he intended to marry her, but when he tried to introduce her, they refused. She was six years older, the daughter of immigrants from El Salvador, and a divorced single mother. Irredeemable. Baba said she was only after his money and, by extension, their money.

After Frank stopped answering their parents’ calls and emails, Baba had taken to wearing his son’s varsity cross-country letterman jacket around the house. She felt a pang, to see him in the jacket, as if a Frank of the future — saggier, slower — haunted the hallways.

Yesterday, Baba told her that they wanted to sell their house and use part of the money as a down payment on a condo for her.

“I can’t take your money,” she’d said.

“It’s our money.” He paused. “Mommy needs you.”

He’d named her executor of his will. Last night, while looking over the paperwork, she discovered they’d written her brother out of the will. Staring at the page, she’d felt like she was choking. Did Frank already know, or did her parents expect her to tell him?

This Christmas was the first without Frank, and as much as she missed him, she also could not forgive him for leaving her alone with their parents. The burden of responsibility, hers alone, even if she’d done it to him first by moving across the country.

Maybe Baba might have been so insistent with Daniel tonight because he’d lost his own son. He could want to redeem himself as a father, as the family elder.

The answering machine blinked on the kitchen counter. Her parents never erased the messages, and the dozen in the queue bothered her. She played and erased them, one by one, keeping the volume low — much as she surreptitiously bagged up clutter around the house and dropped it off at Goodwill. There were several hangups, a couple of telemarketers, and an automated appointment reminder from a few months ago for her father. From a neurologist. She played it again, but the message offered no additional clues.

“Who was that?” Baba asked when she returned to the dining room. He straightened his glasses, which he had begun to wear fulltime in the last year. The huge plastic frames made him seem dependent, at the mercy of something beyond his control. He was the kind of man who left nothing to chance, who practiced and timed driving routes before important events, who developed contingency plans to protect his family in every kind of emergency.

“A friend. From college,” she said. The lie came easily after a lifetime of omissions and deceptions. She had learned how to balance her life against them, to bare only what they wanted to see, and yet their presence always shadowed her. “She’s alone on Christmas.”

“Is she Chinese?” Ma asked. She styled her hair in a 1960s bouffant, never tiring of the glamour she had dreamed was American. Grace suspected she was still trying to matchmake with her brother, harboring the hope he might change his mind.

“No,” Grace said.

“You should have invited your friend to come over,” Baba said. “Always room for one more.”

At the close of the civil war in China, her father’s family fled across the strait to the island of Taiwan. Baba’s youngest brother, Third Uncle, was Daniel’s father. He and his wife were the last to immigrate to the United States, the least educated and the first to have children. Third Uncle and his family had lived in this house for a few months when Grace was eight years old. They slept in her room, and she’d been forced to bunk with her brother. She had resented them, their smelly foods and bad haircuts.

At fourteen, Daniel was supposed to be knowledgeable and cool, but instead she had to explain how to use a microwave. “No metal,” she had scolded, after he heated up a tinfoil-covered dish, causing miniature lightning strikes.

Yet when she and her brother wrestled, knocking over and shattering a vase, Daniel helped glue it together before their parents discovered what happened. He learned English from watching reruns of sitcoms like Gilligan’s Island or The Brady Bunch and game shows like The Price Is Right. She and her cousin used to shout along with the host, “A new car!” In America, if you answered correctly, you could drive into the sunset that very day.

In time, she and Daniel confided in each other. She revealed the mysteries of the schoolyard: “Hella means ‘very.’” “Don’t be a dualstrapper. Only hang your backpack o one shoulder.”

In turn he divulged the mysteries of the older generation, giving her tips on how to be guai, the Chinese concept of good wrapped up in obedience. “Make Baba his tea without him asking.”

She didn’t realize she’d needed his protection and guidance until his family moved to Chicago, where a friend of a friend had a restaurant job for Third Uncle. With the help of a loan from Baba, the family bought a diner, Junior’s, where Daniel worked as a busboy, and later on, as a waiter and a cook. His parents had no savings, no future without him, and Baba still sent them money every month to cover their expenses

A few years later, Daniel had lived with Grace’s family, taking classes in the summer to finish his engineering degree at Cal early. He studied for most of the day at the library, returning for dinner, when Baba quizzed him about what he had learned. Daniel, in turn, coaxed out stories about Baba’s days in graduate school and the start of his engineering career, stories that Grace had heard only in brief or not at all.

If Baba had returned to Taiwan, he might have landed a prestigious government post or become a professor, instead of getting passed up for promotions, forever the foreigner. If he’d returned, he might not have borne the weight of becoming the sponsor for his three brothers and two sisters. He might not have called her good-for-nothing or told her brother he was lazy and useless. He might not have pounded his fist against the dining room table, so hard the chopsticks jumped into the air. All this Grace had pieced together later, but back then, she never knew what might set off her father — if she scraped the car door against the curb, or if her brother played the television too loud during Baba’s nap.

After such blowups, Daniel drove his cousins through the hills to the Lawrence Hall of Science, where they climbed on the fiberglass humpback whale and the double-helix sculptures on the plaza overlooking the bay. If it was windy, he slipped on his hoodie and tugged it over her, the fleece downy as a chick. She’d draw up her knees and tent herself in the baggy fabric. They didn’t talk about what happened, but she always felt more steady and solid afterward.

His final year at Cal, Daniel picked up a flyer for an Asian American Christian fellowship. At the welcome barbecue, he met Phyllis, and neither of them was far apart from each other, or the church, after that.

Now Baba finished dividing the turkey into piles of dark and white meat. He would not stop until the bird was stripped. “I know you want the drumstick.” He reached for Grace’s plate while brandishing the leg impaled on the serving fork.

She shrank back, pleased that he remembered, though also resenting the inescapable loop of his recollection. As a child, she had wrapped paper napkins around chicken legs and gnawed on them. Andy would have been surprised, for now, given the choice, she ate no meat, only fish. She jerked back her plate, causing the drumstick to slide onto the tablecloth. She nudged the leg with her fork and moved her plate to cover the grease spot.

“The wine!” Baba said. Her mother, a real estate agent specializing in Chinese clients, had received two bottles of Chardonnay from a customer. She was going to regift them until Baba had claimed the bottles, calling the wine a proper accompaniment to a holiday dinner. Slipping into the kitchen, he reemerged with a corkscrew and the wine. Grace could not recall a single occasion in which her family had consumed wine, and she was astonished her father had a corkscrew. The cork did not budge under his inexpert hand.

“First Uncle, let me do it,” Daniel said.

“It’s my duty. I’m the host.” Baba pushed and pulled until half the cork crumbled into the wine.

Grace fetched a strainer and glass tumblers from the kitchen. Her parents didn’t have wineglasses. She had come to like wine, which she had each night at dinner with Andy. She never had more than a glass — more, and she might vomit. If she drank too much, her heart pounded in her ears, and her throat seized up. Andy would knock on the bathroom door, checking on her while she splashed her face. She probably should stop drinking, but she couldn’t give up the festivity, the feeling she had entered a wider world.

She asked Daniel if he wanted a glass, and to her surprise, he said yes. His wedding had been dry.

“Let us make a toast,” Baba said. “To Daniel, who will start software consulting next year.”

Daniel stiffened. The more Baba drank, the more he toasted. To his family, to his brother, but most of all to Daniel and to computer programming. Baba’s cheeks flushed and his eyes turned bloodshot, small and red as holly berries. Grace had never seen her father drink but for the occasional Cognac toast at a Chinese banquet.

Her cousin kept up, glass after glass. Once Phyllis put her hand on his glass, as though to tell him to slow down, to stop, but he knocked back the wine without looking at her.

Grace’s phone buzzed in her pocket: a text from Andy, telling her good night. She didn’t write back. Another arrived from her brother. Her chest tightened. Was he imagining them at dinner? She’d see Frank the day after Christmas, before her flight back to New York. She had a gift for his stepson-to-be, the same age as Andy’s twins, who had picked out the Lego set.

Baba raised his glass. Ma shook her head and said something in Chinese, something about medicine. He could be taking a drug that didn’t mix with alcohol. Maybe when her father had told her “Mommy needs you,” it wasn’t that her mother ailed — he did, and he wanted to make sure that Grace would take care of Ma if he turned sicker.

“Da Ge,” Second Uncle said. Big Brother. It could have been another gentle warning. Though his voice was creaky, Grace could imagine him as a boy, looking up to Baba then, now, and always.

Without a word, she pushed back her chair and hurried over to the coat closet, a few steps off of the dining room. She’d seen an old Polaroid camera hanging on a hook.

“I almost forgot,” she called out. She knew how odd she must seem, getting up like that, but she had to put a stop to her father’s next toast. “Picture time!”

She remembered the camera from her childhood, before the advent of slim silver digital cameras. Her fingers brushed against the black plastic casing, the device bulky and awkward to hold. But Polaroids provided a sense of occasion, with its technology that still astonished her — an entire processing lab crammed inside and spitting out a photo then and there.

“They still make film for that?” Daniel asked.

Baba nodded. He took the camera, and then gestured for her to stand behind Daniel. Baba snapped the shutter without giving a warning count. He wanted a natural-looking shot, he often said, but Grace suspected he liked to remain in control. He blew across the thin plastic square, breathing the image to life.

Grace sat back down. As they passed around the photo, the claims began. Second Uncle said her eyes looked like his mother’s. “No, her eyes are like mine.” Ma tilted her head. “The corners.”

Although Grace was present, they spoke of her in the third person. When she was younger, she used to dispute such statements, not wanting to look like anyone else. Now she understood that children were subject to discussion like other kinds of possessions. Her parents, aunts, and uncles never tired of playing this game.

She and Daniel both had close-lipped smiles in the photo. She ached for her brother; he belonged in the picture too. “Daniel and Baba look alike,” she said.

Everyone stared at the two men, searching for the similarities. They had the same round faces, broad noses, and parenthetical creases around their eyes. In unison they shook their heads in disagreement, adding to their likeness.

“Looks skip a generation.” Baba reclaimed the photo from Grace. “Maybe his baby might look like me. But not Daniel.” He swigged his wine. “You know, we learned English from the missionaries. In grade school. First they taught us how to count. That’s the best place to begin, right?”

Eying Baba, her cousin must have wondered if the question was a friendly overture, an attempt to find common ground — or a trap.

“They taught us songs, ‘You Have a Friend in Jesus …’” With a glass still raised, Baba emphasized every other syllable, in a jerky vaudeville beat, thumping his other hand on the table so hard that the glasses rattled. “And He will bring you home.”

He set down his glass. “We learned another song too.” He sang in Mandarin, about mountains and stars. Now the melody smoothed out, the roundness of the notes originating from low in his diaphragm, the song more beautiful than the original. Ma hummed along, and Second Uncle bobbed his head.

“Same tune, different song,” Baba said. “They never knew our version was different.”

He raised an empty glass, streaked with wine. Daniel picked up his fork and jabbed it into the remainder of the turkey.

The last time Grace had seen Daniel, at his wedding almost fifteen years ago, Baba had warned her and her brother about the dangers of being duped by a cult. He fumed that they were throwing away a good education. Daniel and Phyllis sat by themselves at a sweetheart table beneath a red paper cutout of the double-happiness symbol, their heads bowed in private conversation, untouchable and dazzling as movie stars in their wedding finery. Pink tablecloths, paper napkins, gold-rimmed plates, and a bottle of apple cider adorned each table. Luxury, Chinese style.

The newlyweds were leaving for the Philippines, where they would begin their honeymoon and their missionary assignment. No one knew how long they’d remain abroad, or that they’d go from country to country. Third Aunt began weeping as the waiters served longlife noodles, the final course. Baba put his hand on the table beside his sister-in-law’s, the most comfort that he could offer her.

“Can we leave?” Frank had finished his book, whose cover featured a woman in leather armor riding a dragon. Against his protest, Ma dished noodles onto his plate. If she kept his mouth full, he wouldn’t complain.

At the next table, Phyllis’s parents were stone-faced instead of smiling. Parents of both the bride and groom had united in refusing to shake the hand of the young minister, with a dimpled chin and an easy grin — blandly handsome, like a male model in a department store’s Sunday flyers. Baba had advised his siblings not to give money as a wedding present as called for by tradition, because the stacks of red envelopes might wind up in the hands of the church. Better to give a savings bond, for the eventual grandchildren. According to Baba, as a missionary, Daniel would never make enough to support his family.

On the dance floor, Daniel lit up when he spotted Grace. He spun her around and hugged her tightly as the song ended. “Congratulations!” she blurted, wanting to say so much more, but another guest pulled him away.

Driving back from the reception, her father ran through a stop sign. A truck crossing the intersection skidded and honked, and Grace rocked against the seat belt and braced her hand on the door. Did he have anything to drink at the banquet? No — no alcohol had been served. It was his fury that made him reckless.

Closing her eyes, she rested her forehead against the window, imagining her cousin in an Edenic jungle — no, on a beach, in sunglasses — giving a sermon about paradise while blue-green waves lapped against a pristine shore. Daniel chose the spiritual over his obligations to his parents, his religion worth more to him than a career. His mutiny traded one form of rigid belief for another, but in the years that followed, Grace had admired that the choice remained his alone. She’d never been so brave. Never so selfish.

As she searched the kitchen drawers, looking for a knife to slice dessert, Daniel entered, offering to help. He marveled at the pumpkin pie. “It’s as big as a wagon wheel!”

Ma had stockpiled it from Thanksgiving, buying it from a warehouse superstore and freezing it until now. It had been defrosting on the counter all afternoon.

“Thanks,” she said. “We can carry it together.”

She wanted to apologize for her father, though Baba had a duty to advise and command that Daniel must understand. That was why he endured this meal.

“None for Phyllis,” he said. “She hasn’t had much of an appetite lately.”

“How’s she been?” Grace had wondered why her cousin and his wife, both in their mid-thirties, had waited so long to have children. Maybe they’d wanted to focus on their missionary work, or wait until they returned to the United States, for better schools and medical facilities. “It’s a lot of change at once.”

“It’s not the first,” Daniel said. Grace understood then that Phyllis had miscarried, maybe several times. Not knowing what else to do, she took both his hands into her own, clasping his knobby knuckles and clammy skin.

“Now God has blessed us,” he said.

She didn’t know how to respond to such a naked expression of his beliefs, as if he’d broken apart his breastbone to reveal his raw wounded heart.

“I’m excited to meet my nephew.” She released his hands and stared down at the glossy surface of the pie. “Or would it be my second cousin?”

“He’ll call you Ayi,” Daniel said. Auntie.

Her phone buzzed, a call from Andy. She let it go to voice mail, but when he rang again, she apologized to her cousin. Turning away, she picked up.

“Aren’t you asleep?” she asked.

“I can’t find their gifts.” The gifts that his daughters had been on the verge of discovering the other day, that she’d whisked away while he distracted them. Grace wanted to have children someday too, but maybe she wouldn’t be able to, if she waited too long to get pregnant. Maybe she might struggle too.

“Look under the bed,” she said.

“Already did …”

“In the green suitcase. But save what I got the girls for when I get back,” she said.

“I will.”

“Love you too,” she said, louder than before, to make up for whispering last time.

After she hung up, Daniel cocked his head at her, making no effort to pretend he hadn’t been listening.

It could have been the jet lag or the wine, but she felt too weary to keep hiding. She’d convinced herself secrets were necessary. Yet the secrets also turned her into a stranger to her family — to herself.

“The guy I’m dating, Andy. His daughters, they’re twins.” The words rushed out with the force of a stubborn champagne cork popping off. He was from Boston, and worked at a tech company, she continued, unsure of what to say about him.

“Your parents … ?” He glanced back at the dining room.

“Don’t know.” She sliced the pie, wiping the blade after each cut.

He locked eyes with her. “They should,” he said.

“I can’t.” Panic fluttered through her. He didn’t know Frank had been disowned. Such information, once leaked, would spread through the family.

“They should,” he repeated.

“Not now,” she said.

“You shouldn’t lie to them,” he said, his tone righteous and scolding.

She clenched the pie server. “You — lecture me? You abandoned your parents!” They were alone at Christmas in Chicago, alone for a long while to come. She unstacked the dessert plates with a clatter and began to serve slices.

He slid plates toward himself. Their hands busy, they didn’t have to look at each other.

“God provided,” he said.

“Baba provided,” she said.

Daniel grabbed a handful of forks, and when one fell to the floor, she could tell he had to restrain himself from flinging the rest. He scowled, transforming himself: Baba’s expression reborn on his face. Did he see Baba in her expression too, in her reproach?

Baba called for another toast. “To your success in programming!”

“Maybe. Sure, sure. Whatever you say,” Daniel said.

“Did everyone hear that? Congratulations for Daniel, who will start working in computers next year. Cheers!”

Everyone went through the musical ritual of clinking glasses. Phyllis had gone pale, her forehead furrowed in fatigue, but she gamely raised her water glass.

“Maybe Grace’s boyfriend could help me find a job,” Daniel said.

She almost knocked over her glass, hands trembling.

“Grace doesn’t have a boyfriend,” Baba said.

“Too busy,” Ma said. The reason Grace stated, and her parents accepted, for her infrequent visits home.

“Andy,” her cousin said. Grace opened her mouth but found herself unable to speak.

The knowing expression slipped off Baba’s face. “Xiao Mei?” he said. Little Daughter, how could you, he didn’t have to say. Your brother, and now you? Ma rubbed her temples, just as stricken.

Phyllis grabbed Daniel’s hand, whispering in his ear. She rose to her feet. “Thank you for a wonderful dinner,” she said. “But I’m exhausted. It’s past my bedtime.” She wobbled, and as her eyelids uttered, she crumpled toward the floor.

Ma screamed as Daniel caught his wife. Her hair curtained her face, her head lolling against Daniel’s chest. Her legs fell open, her hem riding up to reveal her knobby knees.

Together, he and Baba carried her to the living room couch, and after a moment, Phyllis revived. She traced her thumb along Daniel’s jaw, through his tears, and he kissed her hand. They mesmerized Grace, their strength and their faith. The kind of love given wholly, taken wholly, that her brother must share with his fiancée, and that she yearned for with Andy.

Daniel touched his wife’s belly. “He’s kicking!” The light fabric of her dress twitched, drops of rain falling on water.

Baba appeared with a mug of tea.

“Chinese herbs?” Phyllis asked.

“Lipton.” He showed the orange tag at the end of the string.

Everyone laughed. Baba locked eyes with Grace, to show he had not forgotten. After the guests left, he’d question her. She had questions of her own. She’d withheld so much, for so long, that letting go seemed a relief.

Phyllis took a few sips and swung her legs around to sit up. She smoothed her dress around her knees.

“We should go,” Daniel said, stroking her hair.

Grace fetched the Polaroid of her and Daniel. “Here.”

Daniel studied the photo for a few seconds. “I have pictures

of him,” he said. “My son.”

Everyone turned to look at the high dome of Phyllis’s belly. “We have printouts from the sonogram,” she said. “In the car.”

Daniel hurried outside, and through the bay window, they watched him fumbling in the front seat.

“What’s his name?” Grace asked.

“We won’t decide until he’s born,” Phyllis said. “You can’t tell until then. What will fit.”

After Daniel returned, he spread the sonogram printouts on the coffee table. He pulled out his digital camera, explaining he’d filmed the checkup. Everyone clustered around its palm-size screen, and suddenly they were plunged into the watery motion. The silvery blob — was that a fist or a foot? The baby’s features might resemble his father’s, his mother’s, echoes of each generation from the beginning.

The heartbeat uttered faster than thoughts, a hollow, whistling, croaking sound, a primal whisper. His head nodded to the music of the body, his face blurred in the murk, not yet visible to anyone. He was swimming, tiny hands swaying in the tides.

Excerpted from Deceit and Other Possibilities, copyright © 2020 by Vanessa Hua. Reprinted by permission of Counterpoint Press.

If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.