The Cut is publishing excerpts of books coming out during the coronavirus pandemic. Before each selection, join us for brief interviews with the author.

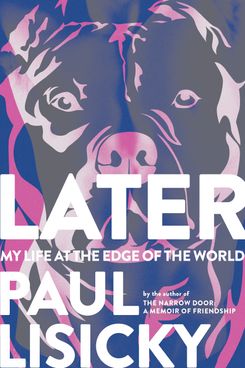

In 1991, 30-something Paul Lisicky moved to Provincetown, Massachusetts, where he began establishing himself as a writer and found a home among the town’s gay community. But, as he details in his newest book, Later: My Life at the Edge of the World, Lisicky’s sense of belonging grew complicated by loss when he saw friends and lovers begin to succumb to AIDS. The Cut’s senior culture editor, Kerensa Cadenas, spoke to Lisicky about his memoir, which came out March 17. Below is an edited and condensed version of their conversation.

One quote from your book that I’m going to think about for a long time is “What else do you do when the world is ending,” which obviously feels apt right now. How were you feeling when you wrote that?

I feel like the world has been ending throughout my entire life and doing it in different ways and at a different intensity depending on the crisis of the moment. And sometimes I just wonder whether that’s human experience, you know? And it’s not to say the world isn’t physically in danger when we think of climate change and the other forces that are taking this planet toward an ending. But in terms of this book, I think it really wants to be faithful to experience. And it’s distrustful of those global statements.

That totally makes sense. Obviously, for certain people this is not the first time that their world has ended.

Yeah, exactly. I have a social media friend who might be close to 70 and said in a post, Look, this is what happens. This is the feeling of being around and being alive for decades and decades. It wasn’t that she was judging people who were anxious for the first time, but in a way that was her wisdom. She has experienced the end of the world over and over.

Noah and I sit in the left side of the Wellfleet Cinemas, not so far from the front. Though showtime is almost twenty minutes away, the theater is packed. I’ve never seen every seat filled, especially in the dead of winter on the Outer Cape. We’re here to see Philadelphia, the first big-budget movie about AIDS. It has real stars, people whom everyday people like: Tom Hanks, Denzel Washington, Joanne Woodward, Antonio Banderas. Bruce Springsteen sings its theme song, “Streets of Philadelphia.” I’m skeptical about it as I’m skeptical about all things Big—Big songs, Big novels, Big ideas, Big countries—all things Big have an inborn arrogance to them. As well intended as they might be, they are finally about wealth, accumulating it, and I can smell the machinery that wants to draw people in, that wants them to keep coming back. Big statements aren’t for people like us; they’re for people who see movies just to talk about movies—such as why you’d see a football game. They are for people all too happy to feel pity for people over there, miles away from the epicenter, anyone not them. Big statements hold a wet fingertip out to the wind. Big statements are inflected with a certain kind of self-congratulation, moral superiority. They’ll say: We have cared for you all along, when you know the truth was always more complicated. And how could Hollywood not get it all wrong, turn the dying into saints, engraving in us the predictable cathartic responses?

On the other hand, it’s relief to be seen—queer people, people with AIDS, survivors, HIV-negative people: all of us. How long have we been erased? And if we haven’t been erased we’ve been represented as depraved, weak. Not that some of those representations aren’t hilarious: Joel Cairo in The Maltese Falcon, Sebastian in Suddenly, Last Summer. Enough.

The theater goes dark. I’m watching characters move across the street, but thinking more about Noah holding my hand, rotating the knuckle of my thumb with his own. Is there anything more satisfying than having your significant other holding your hand out in public, at a movie? Straight people take this for granted, but queer people? We can hardly wait for the lights to go down, and once the movie gets going, the real happiness begins: Noah’s hand in mine.

But the film is so determined not to offend, not to get things wrong, it’s managed to situate itself in a weird in-between place. It isn’t exactly bad, but? I’m watching the way I would watch a documentary about dying dolphins. And I say that loving dolphins, but they’re not me. Every time a potentially wrenching exchange happens on the screen, Noah squeezes my hand until it feels like the manual equivalent of Morse code. The movie isn’t afraid to say This Is the One Story of AIDS (no matter Longtime Companion, no matter Brother to Brother, no matter The Man with Night Sweats, no matter The Body and Its Dangers, no matter People in Trouble), and I’m annoyed that it doesn’t intuit there are countless stories that will never make it to the screen—stories of black, Asian, Latino people, stories of women. Hollywood has the power to sear a narrative into the collective imagination, and though I resent that power (what about all those film executives still in the closet?), I sit tight and obey. I won’t start muttering complaints while I’m still in the theater.

And then? A man stands up halfway through the film—abruptly. It is a bright scene, as the whole theater is illuminated. He is crying like a baby, a baby boy, and it wouldn’t be so wrenching if he wasn’t such a tough-looking guy, leather vest, Levi’s, salt-and-pepper muttonchops. I’ve often seen him around Town, always in his leather bomber jacket and white T-shirt, always too butch to even look in my direction. He can’t stand it—once you represent something it’s real, and up until now AIDS has been only a horrible dream. Now he knows it’s an emergency, and he stands up, weeping. I want to protect him. I want him to stop breaking my heart, I want him to keep crying, as nothing up on the screen feels as powerful as this, or the absolute discomfort of seeing it, listening to it. He walks out, breathless. I don’t know whether he’s crying for someone lost, or for himself, or both. Maybe he’s crying because he thinks he’ll have none of the people once closest to him (his parents, his sisters) when he dies, and he must suffer through this well-intended movie that insists every life is of purpose, every life shaped by logic. He has never known such good fortune. And if he should get sick? His friends? His friends, while well-meaning, might turn out to be flakes when they’re most needed. They have bailed on him before and they’ll bail on him again, and what should he expect when he’s loved them for their spontaneity and quick passion and unreliability? Dependable people, as he knows, are boring people, and he knows what it’s like to abandon others too.

For a while I don’t see the man at the gym, at the A&P, or at the coffeehouse at the Mews. Not that I’m exactly keeping an eye out for him. That’s just how it is when disappearance is as routine as breakfast.

Excerpt from Later. Copyright © 2020 by Paul Lisicky. Used with the permission of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, graywolfpress.org.

If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.