It’s possible to drown in stories of collective grief right now. The searching ones about life as many knew it, now suspended between a longing for the before and the queasy uncertainty of what the after will bring. Will we be able to crowd bars again? Wriggle out from under the housemates that have been grinding down our nerves? Touch hands and faces and hug without the fear of a pathogen nestling its way into the embrace? And, of course, there are truly somber stories, the loved ones lost or impoverished. And the slow-motion tragedy that will certainly claim more; a virus that is determined and haphazard has come for us all.

Black Americans are no strangers to grief, COVID-19 or otherwise. There’s the collective mourning attached to the disproportionate toll the virus has taken on black communities. And the crippling anxiety of a life trapped indoors, compounded with the dangers we know have always awaited outside. Our before and our after contain one very real constant.

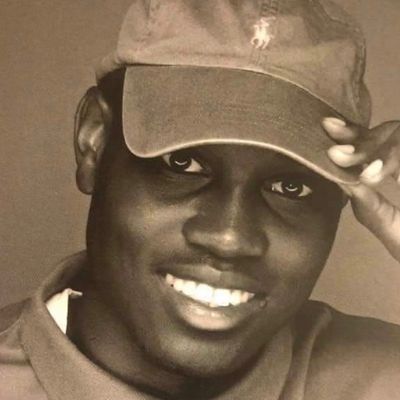

Today, Ahmaud Arbery would have been 26 years old, had he not been killed while jogging through his neighborhood when two white men, 34-year-old Travis McMichael, and his father, 64-year-old Gregory McMichael, attacked him with a shotgun, and later claimed that they thought he was a “suspect” linked to recent neighborhood break-ins. A viral video of this murder snaked its way through social media this week, dredging up all the trauma of murders past and sparking necessary public outcry. I avoided watching it for a long time because I knew it would sink a rock in my gut that would sit alongside all the others. That if I let myself, the grief could consume my days — Arbery’s death would sit next to all the other stories of other unarmed black men I’ve had to watch die on small screens without justice, and the virus strapping the black communities near where I live, my own grandfather who died of it two weeks ago, and my fears for everyone that I really just want to make it out alive.

But in the end, I did watch it.

Arbery struggled for the gun as he was being shot at, before collapsing to the ground. That was back in February. Only yesterday, on the eve of Aubery’s birthday, did the police arrest and charge the two with murder and aggrevated assault. That the McMichaels so casually projected criminality onto this young black man, instigated a fatal altercation, and slept soundly at home for more than two months should sound obscene, even to folks who are well acquainted with how racism in this country works.

The charges brought me little comfort. It’s difficult not to think of them as a foreshadowing of the disappointments to come. As James Baldwin once put it, “You always told me, ‘It takes time.’ It’s taken my father’s time, my mother’s time, my uncle’s time, my brothers’ and my sisters’ time. How much time do you want for your progress?” The excruciating waiting, the anguish that a lot of communities have felt in ways they cannot name, is punctuated by days like today.

The racist vigilantism and indifference from the authorities calls to mind the killing of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman, which happened eight years ago this month. And Botham Jean, who was killed in his Dallas apartment in 2018. To name but two of the too-many-to-count. And if the constant barrage of death were not enough, the languid period between watching someone’s humanity snuffed out and waiting to see if anyone will be held accountable is its own tortured form of stasis.

It’s a specific grief. One that if you’re black, you have to anticipate, and spend a life preparing for, despite the futility. Charles M. Blow laid this bare in his New York Times column this week, “Slavery was legal. The Black Codes were legal. Sundown towns were legal. Sharecropping was legal. Jim Crow was legal. Racial covenants were legal. Mass incarceration is legal. Chasing a black man or boy with your gun because you suspect him a criminal is legal. Using lethal force as an act of self-defense in a physical dispute that you provoke and could easily have avoided is, often, legal.”

The gnarled feeling in my chest is the thing I can’t name. My stomach is running out of room for all the pits. The feeling that a video can capture the last few moments of a young man’s life but not all the ways its contents shape life for those of us who are left behind — still anticipating and praying that cameras somewhere are rolling.

When I look at the sepia photo of Ahmaud that accompanies many of the stories about his death, I see the way the Polo logo hits off of his hat and shirt. The way his bright smile rounds his cheek, producing the dip of a barely-there dimple, I think of the tragic yearbook that it joins. Of a much younger Martin’s red Hollister shirt. Or Castile’s cascading locks. Or the glint of Sterling’s gold tooth. Today people are jogging to commemorate Ahmaud. And it’s likely that next May and the May after that, we’ll call forward this photo in remembrance on his birthday, a kind of gruesome congratulation that the possibility of Ahmaud’s life wasn’t forgotten. And then I get angry with myself, because it doesn’t really help allay the ache of inevitable grief to situate Ahmaud among these men. You could fill the infinite expanse of the internet with black people that America has failed in this way.