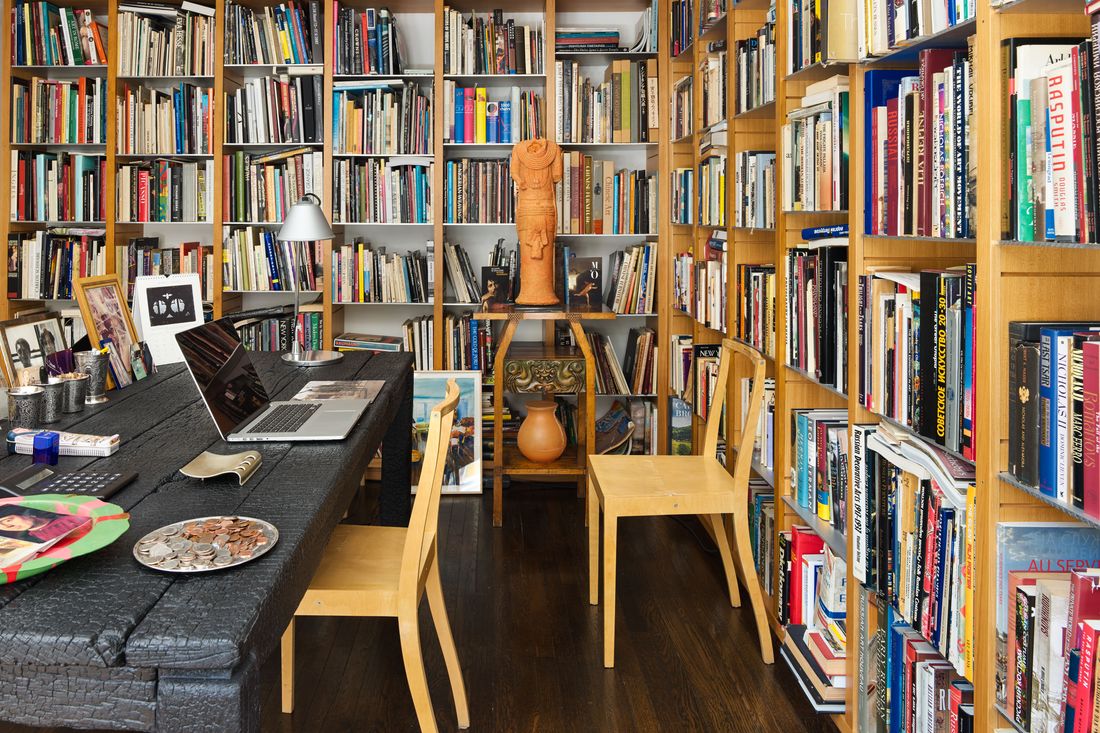

Books, jokes Pierre Apraxine, who has a lot of them, are “like a flood. Slowly, slowly there are more and more, and by the time you find a place for them, it’s too late.” He laughs when he says this; of course, he loves books — he is a scholar and curator. His two-bedroom in a classic West Village Bing & Bing building is full of them, cohabitating with his eclectic and erudite collection of art, furniture, and artifacts. “What you see now are basically the things which have passed through my hands and stayed,” he says. “Most of the things that I ‘collected’ found their place in museums and institutions and so on, but the things that I am surrounded with — they got here and never left.”

“I’ve never quite known anyone with an eye like Pierre’s,” says his close friend and longtime Museum of Modern Art trustee, Barbara Jakobson. “And you know he’s a Russian count.” Apraxine was born in Estonia in 1937 and educated in Belgium before arriving in the U.S. as a Fulbright scholar in 1970. The New York that embraced him then was bursting with the messiness of new ideas. “It was like I fell in a soup,” he says, laughing again. “And I was trying to swim. Everything seemed possible; all the boundaries were being tested. I had a chance to be part of that exploration. You know, everything was moving. It was an invitation to try; that is what New York was all about.” He worked for a while at the MoMA, where he met Jakobson (who helped him find this place 23 years ago), and from 1976 to 2007, he was the curator for the Gilman Paper Company Collection, headed by the late Howard Gilman. He renovated the apartment in 2007 with the help of his friend architect Christian Hubert.

Apraxine was a self-taught connoisseur of early photography. Along with Sam Wagstaff, John Waddell, and Paul Walter, he started frequenting auction houses in London and dealers in Paris, astonished to realize he could “buy a masterpiece of a territory that is unknown, this primitive photography.” Apraxine would go on to amass more than 5,000 photos for Gilman, a selection of which appeared at the 1993 show “The Waking Dream,” which he co-curated at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Later, he curated “La Divine Comtesse: Photographs of the Countess de Castiglione,” an exhibition that traveled from the Musée d’Orsay to the Met, which centered on the 19th-century Italian aristocrat and onetime mistress of Napoleon III who spent ruinous amounts of money creating hundreds of lavish photographs reenacting scenes from her own life. In 2005, he was honored as Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Republic.

Apraxine reports that his life in lockdown is not so different from his days before; he spends time reading and taking care of business as a consultant curator for the photography department at the Met.

I ask him about the Russian Empire furniture; he bought the pieces years ago in Paris, and when he had them reupholstered, it turned out the springs were original. “They have had quite a journey. The sofa bears the wax stamp of the City of St. Petersburg Customs. Therefore, the suite left Russia before 1914. I have a fantasy that Pushkin could have sat in one of these chairs.” When asked what one object he would save in a fire, he answers, “It’s difficult to say. Every one of them has a meaning, but I think I would save a triptych of an enameled icon that comes from my mother’s elder sister that is typical 1900s, but somehow it managed to survive all the moves over the years from Estonia, Belgium, and New York, and somehow it is still with me.” He adds, “Some things come here and have a life of their own. They decide to spend some time at my place; it’s a good address for them and then they are on their way someplace else.”

*A version of this article appears in the May 11, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

More From Design Hunting

- A Ranch House Turned Modern Oasis

- Home Is Where This Designer’s Art Is

- Transforming a 1980s Time Capsule