There was a phrase that my uncle used to say over and over when my mother — his baby sister — was dying. Even before we knew what was happening. Time is of the essence, he said in September of 2004 as he sat with his siblings in my aunt’s condo in Connecticut, trying to understand why my mother’s body had been giving way. Were these stomach pains really caused by irritable bowel syndrome, like my mother’s physician suggested? Could visiting traditional Chinese medicine specialists in Flushing help? In my uncle’s eyes, if we used our time wisely, we could try to answer these questions. If we prepared enough, we could cure her of any illness.

Time is of the essence, my uncle said again just a few weeks later, squeezing my shoulders at a hospital in Hartford when my mother was first diagnosed with terminal cancer. The doctors said she only had a few months to live. I was just 13, but I assumed it would be an inevitable, painful death. Still, my uncle wanted to race the clock; he wanted new doctors and new treatments. He talked about liquidating some of his assets and encouraged my father and his sister to do the same, making a plan to scrounge enough money for my mother’s treatments and hospital bills. He’d protected her when they were children in Guangzhou, and then teenagers in Hong Kong, and later, adults in the U.S.

He was always this way — full of a frenetic, anxious energy that seemed to say his sheer will alone could make something true. For much of my childhood, I thought he was a hulking, giant man because of his enormous personality and the way our other relatives fell in line behind him. It was startling, as an adult, when I realized that he had only a handful of inches on me, and I was barely taller than five feet. When I was a kid, he was the uncle I was most afraid of because of the way he’d tease: Hey, what happened to your face? All these pimples. Too much junk food. Pinching my cheeks, squeezing my head under his armpit, a little mean in a way that mortified me, but was at least honest.

Time is of the essence, my uncle told me, when just a week and half later, my mother unexpectedly fell into cardiac and respiratory arrest, and was intubated and put on a ventilator in the ICU. I wasn’t sure what my uncle meant then — was he still hopeful? But I understood that this was his way of preparing for his sister’s inevitable death. Still, we were waiting for the rest of my mother’s family to arrive so that we could take her off life support. Time seemed beside the point, now.

When I think of a collective sense of grief, I think of how easily I became distant from my mother’s family, including my uncle, during those months and years after her death. As we all mourned, I watched us retreat into ourselves.

My extended family could not speak to one another in our grief. There was too much blame to assign; too many emotions left unprocessed; too much regret about what hadn’t been done. Without my mother, we fell into our own pockets of Connecticut, where there were no neighbors who looked like us; no restaurants in which we could convene that served the Cantonese food my parents grew up eating in Hong Kong and Guangzhou; no places where we could dependably hear Chinese dialects. Years passed before we found our way back in touch.

When governors began to issue stay-at-home orders in March, I found myself echoing my uncle’s mantra.

Time is of the essence, I thought, whenever I read the news about the uptick in hospitalization rates or death tolls. Time is of the essence, I thought, when I heard stories about businesses shuttered and families finding it impossible to pay bills.

Still, in isolation, my family was in stasis, unsure what to do with all of our time. So we reached out to one another. My extended family’s sprawling, 19-person group chat that spanned three generations, began ticking with new messages.

Mostly, there were questions directed at the two doctors in the thread, updates from people’s jobs, or memes about Tiger King or of Bruce Lee mid-kick, encouraging people to stay six feet away. Then, there were the concerned discussions about the anti-Asian racism we had already experienced, or heard about.

Watch out, coronavirus is coming this way, one cousin reported hearing at Trader Joe’s, as he walked down the frozen-food aisle and was about to pass a man and his son.

Be safe out there, we texted, making glum jokes about being unsure if we were more afraid of the racists or the virus.

Or there were messages from my uncle that I pictured him painstakingly, slowly typing. His texts boiled down to things like this:

Salt water or a ginger drink can kill the virus in the throat area. (No, someone responded, that is fake news. No evidence that this is true.)

How long do you think we should leave home delivery groceries outside before bringing them in the house? (Our answers varied; a long time, like three days at least; disinfect them!)

Each time I read his messages, I felt a pang of concern and imagined him pacing in his house in Connecticut, where he lived with his wife, worrying the hours away.

I told myself that I would call him, that I would also reach out to his sister and my dad, both of whom live alone and are in their 70s. I did the latter two, asking my aunt and father in separate phone calls how they were doing and what they were eating. My aunt was scared, but okay. She was still concerned over whether or not I was eating enough vegetables, since she could see from our video chat that my skin was breaking out. My father insisted that life under these stay-at-home orders isn’t too different from his normal life, since he rarely sees people or leaves his house anyway. I don’t know if that’s a good thing, I thought, but still I felt relieved. I did not call my uncle, even though each Friday, I resolved to reach out to him over the weekend or in the next few days. I still did not know how to talk to him, still felt a little hurt from all the years after my mother’s death when we never saw each other, still worried that conversations with him would catalyze a latent wave of grief in him, or me.

You’re so much like your mother, he told me a number of times. That’s why it was so hard to see you and your sisters. You remind me so much of her, and after I see you, I can’t stop thinking about her. In those weeks when I thought about calling him, I could picture him answering the phone in his teasing way: Katelin, Katelin, Katelin, so you finally call me? You finally remember your Kaufu?

For the past couple of years, I’ve been working on a memoir about my family’s collective grief, gathering stories from my sisters, father, aunts, and uncles. Conversations about my mother with family, and especially my uncle, often began by discussing her illness and the fallout of her death. But they quickly revealed something — not quite grief, not quite isolation, not quite longing — that we could only talk around, never about. I only knew that it felt so linked to our family’s history of immigration.

For much of our time in America, we — like many other immigrant families — went about our lives on the fringes of our community. We felt rootless in place, constantly trying to carve space for our traditions. We rarely met others like us in the mostly white Connecticut suburbs where we lived, and for the most part, lacked the shorthand of Christianity or whiteness to ease us into social situations with our neighbors, classmates, or co-workers. But when my mother was alive, we had each other; my mother and her siblings became even closer and each of their households tightened their circles. We could never put to words how these types of loss infiltrated our units, or how they ultimately bound us together.

This pandemic has isolated the country in so many different ways — physically and psychically. When I read the news of virus-fueled racism, two memories come to mind: the first is when a neighbor called me a “chink” while we played together, vocabulary that she likely heard from her parents about mine; the second is when some parents at the local private pool club, with mostly white patrons, became angry when my older sisters swam as guests of a friend — a protest likely rooted in its own ugly, racist history. These instances were often borne out for my family in quieter, humiliating ways like these. My parents, sisters, and I were usually the only ones in these situations who understood them to be as insidious as they were; they felt inevitable and unsurprising, though they were always still aggressive. There were no consequences then, and we seemed to know that there would be none in the future.

It’s not just the president saying “Chinese coronavirus,” that brings on these shimmers of frustration. It’s not just the increase in anti-immigrant rhetoric or policies, or the casual, lazy resurgence of a slur. It’s not just the increase of racism and violence against Asians and Asian Americans that makes a total and undisputed belonging feel far off. It’s not just the staggering death rates, especially among black, Latinx and Native people. It’s not even the physical separation and its loneliness. It’s all of that plus the uncertainty around our own proximity to death, and the quieter losses that will only reveal themselves later.

After all, how could we attempt to steel ourselves for all the ways these American systems have failed us — were never meant for some of us — and have left our loved ones and the most vulnerable to die? It’s the time it takes to learn the answers to questions like this that feel so excruciating; it’s seeing tragedies unfold in slow motion; it’s the plodding approach of an inevitable grief.

Despite his timing, my uncle’s mantra was ultimately one of hope, which is a useful emotion to channel in times of uncertainty. We know that in this moment, time is of the essence. That the days and weeks and months ahead will only deepen the disparities that already existed in this country, and it might take generations to recover.

I operated at the start of this pandemic as though my check-ins with family — the group chat, the phone calls to my aunt and father — would protect them, and me. I realized, with a strange and mottled dread, that these calls felt like a form of emotional doomsday prepping. I was bracing for so many shapes of grief, including their loss. And checking on them felt like being able to keep the worst at bay.

But that was foolish.

One recent morning, my oldest sister called to tell me that our Kaufu was dying.

He had tripped and fallen at home. The fall triggered a heart attack and a brain hemorrhage. He was not going to make it. My uncle was only in his 60s, which was far too young to die this way, I thought. But now he was in a hospital in Connecticut on life support. His wife and sons made arrangements for the end of his life in the parking lot outside. I thought of my uncle’s last few text messages in the group chat, worried about disinfecting groceries.

It wasn’t coronavirus? It was a fall?

Something terrible and ugly seized within me.

Then came a suffocating, undulating anger and fear that I had been cowardly and had gravely fucked up. For the rest of the weekend, I felt dazed. I knew this wasn’t exactly rational. Still, I thought, I should have called. Why hadn’t I called him? In the long stretch of quarantine days, in the weeks of hand-wringing and worrying, I’d inexplicably run out of time. How? I kept asking myself. How could you let this happen? Time flattened. It was no longer of the essence.

I had hoped preparation might make the fallout of grief softer; that just talking to family alone would stave off guilt. That writing a book about loss might make me more equipped to deal with it and to finally attend to the conversations about family that I’d avoided for more than a decade. But you can’t prepare for everything; you can’t ready yourself for the way loss shocks and stuns and debilitates. How, despite yourself, it makes you litigate, then relitigate, a wave of memories that had previously seemed inconsequential. Did he really think I didn’t send him a wedding invitation — that it didn’t get lost in the mail? Was he mad that I never called these last few weeks? Did he know that I loved him, even if we argued?

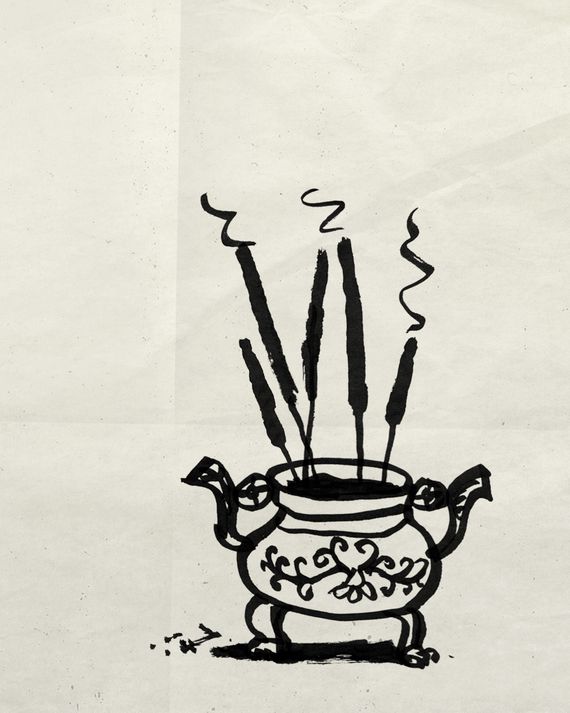

On the day of my uncle’s burial, I woke early, restless. Only a handful of his immediate family in Connecticut would be able to attend. I knew that the rest of my relatives there were likely burning incense and joss paper for him in their homes. I gathered my own incense and lit three sticks in my kitchen, watching them smolder.

Take care of yourself, okay, I said. Look after all of us, okay? I hoped that now, in death, wherever he was, that he no longer felt so pressed for time. That time could stretch on in a way that permitted him to worry less and to soften. Watching the paper burn, hundreds of miles from my family, it felt like an act of resistance — against this loneliness, this isolation, this battering of grief.

Kat Chow is a reporter and writer based in Washington D.C. Her memoir, Seeing Ghosts, is forthcoming from Grand Central Publishing. She tweets at @katchow.