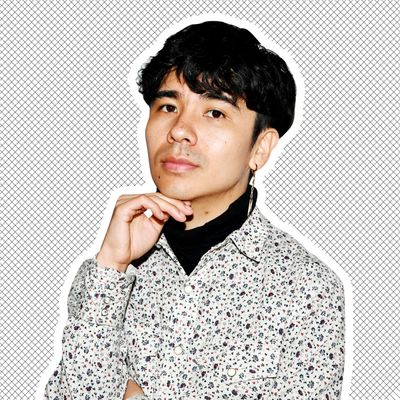

Pride Essentials asks our favorite LGBTQ+ artists to share the influences that have made them who they are today.

Ocean Vuong is a poet, writer, and professor whose work draws on his childhood as a Vietnamese refugee growing up in Hartford, Connecticut. His best-selling, 2019 debut novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, is written as a series of letters to the narrator’s mother, absent father, and first love, a boy named Trevor, with whom he has a fraught relationship. The book — and much of Vuong’s oeuvre — is a tender meditation on the immigrant experience, queerness, and love. Vuong won a MacArthur “Genius” Grant last year and is currently an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Below, he shares the texts, TV shows, and places that shaped his identity growing up.

The Baptist Church

Going to the Baptist church in Hartford, where my friends attended — a mostly Black and brown church — and hearing gospel music [had an impact on my identity]. The sort of gaudy exuberance, the atmosphere, the articulated acts … [it was] an expansion of what is performatively possible. The music and the colors and the dancing and the joy, to me, was part of what I understand as art-making and theater, not just as something done onstage or you consume as a show but something that was a part of the daily practice. In a safe way. Because a lot of times, that space is not necessarily safe or inviting for queer folks, but it was, oddly, in that world, where I started to see what was possible, with how the sermon was performed and how everything was tied to the body.

Shining Time Station

Are you familiar with [the TV show] Shining Time Station? It was basically these androgynous trains. Talking to each other. And then in the middle of it is George Carlin inside a jukebox, literally just like George Carlin inside. And it was so bizarre but powerful because it was such an escapist enactment of the imagination. You can listen to the music, but you can also be inside the place where music comes from. It just broke all the rules of logic, the rules of physics. And then we had these moody, androgynous trains with androgynous voices, and it ends with like this sunset, this sad sunset scene of a train going into the distance. And I remember just watching it and crying; it was so bizarre. You have this like puppetry of the trains, and the last clip, it’s a realistic train setting off into the sunset, and it was just … so extra.

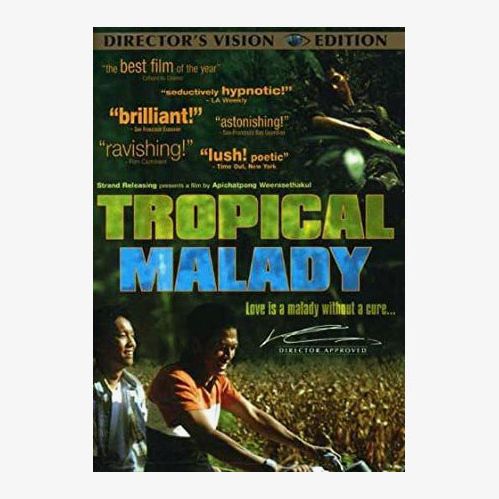

Tropical Malady, by Apichatpong “Joe” Weerasethakul

I came to film really, really late. I was the poor kid, and the TV in the house was this thing with an antenna, with tinfoil on the antenna, and that was it until I was in my teens.

So I’m still catching up on film. My relationship with films, particularly queer films, is still relatively new. I just saw Tropical Malady by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, a Thai director who was influential to Barry Jenkins. That film was so incredible because it was about these two Southeast Asian male lovers. And it’s just quiet; it’s mundane, it’s “normal.” And their love was not just a spectacle. And then it just turns into a ghost story! That transition was just so Asian, so specifically Southeast Asian. And I just thought oh my God, I’m so behind.

It’s really great to be a quote-unquote queer writer and queer scholar and still feel like there’s so much more I have to get to. It just proves that in terms of media, we have such a wealth here and it’s just a matter of, you know, will people pay attention to it? Do we have the platform to amplify it? The artists, the stories — we’ve always been here, we’ve always been making these stories.

Thunder Cake, by Patricia Polacco

[This children’s book is] basically a story of an immigrant grandmother from Russia and her granddaughter cooped up in a house as a storm is coming, and it’s a big, big storm, it’s a thunderstorm. And instead of boarding up the windows, instead of going into the basement, they make a chocolate cake. And to me, the strangeness of that made perfect sense. With family members coming out of trauma, coming out of geopolitical violence, if the maternal leader of the household performed this act of madness and joy in the face of disaster, it seems “insane” and yet it makes perfect sense, that when you are powerless, you decide your own joy in the face of destruction.

Of course, I wasn’t thinking about all that when I was reading it, but I kept returning to that story. I said why was that so fascinating to me? It was a very queer act, even though there were no queer characters in that story, the act itself, the act of defiance and the act of deciding to be extra, to insist on something that’s supposedly useless, that’s the critique that we all get: That queerness is decorous, it’s not a utilitarian thing, and therefore has no value.

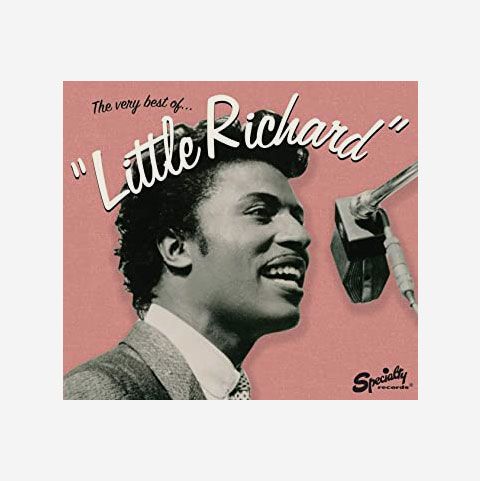

Little Richard

Little Richard, his life, his work, his performance. His performance of performative drag, the blurring and the troubling of gender lines. He was doing this in the ’50s. And, you know, the reason why he did this was because he had to put on makeup to go into the white clubs because the white bouncers and the white owners of these music clubs would fear that if he was too masculine, he would be a threat to the white women in the audience. And so it was interesting that the creation and enactment of Little Richard came out of a subversion, out of a fear of Black masculinity and of Black men. And so he, in order to make a living and sort of make a life, he had to bend what gender norms there were out of racism, and he embodied it as a source of power, and he became a leading figure for James Brown, for Michael Jackson. And it came out of this incredibly queer act of subversion. I think about that so often.

If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.