When I spoke to Marc Jacobs in May, he’d just watched Martin Margiela: In His Own Words. “I thought it was probably the most moving, touching, beautiful documentary I’ve seen on fashion in—forever,” he said.

Since moving into the Mercer Hotel, where he lived during the lockdown (he and husband Char Defrancesco’s home in Rye was being renovated when the state halted all construction), Jacobs had been doing a lot of thinking and watching. He’d been posting on Instagram with incandescent resolve—in huge platform shoes, in purple eye shadow, vamping as Edie Beale.

I asked him what he liked so much about the documentary, which revealed the mundanities of Martin Margiela’s childhood in Belgium—the wigs his mother sold at his father’s hair salon, a Barbie-doll jacket—that fed his imagination and, thus, the designers Margiela influenced, including several in this story.

“In my hotel room, I feel like 9-year-old Marc, who went to his room to escape his dysfunctional family, and in my little room, in my little world, I could be whoever I wanted to be. I was safe, I could play with dolls, I could put glitter on construction paper and hang it on my wall. So any insight into Martin’s youth, I thought, This I get.”

During the years when Margiela was active—he quit in 2008—he avoided the media, preferring to let his work speak for itself. There was no Instagram to worry about then. Jacobs said he couldn’t help but note Margiela’s decision to get out just as the internet became so important.

Even before the coronavirus, because of social media’s predominance, Jacobs knew things were amiss. “Social distancing was something we have done by this addiction to phones, iPads, and computers. And people, even when they are given the gift of a live experience, don’t show up for it. They aren’t completely there. A couple of years back at a show, I insisted that everybody put their damn phones away and just look at the clothes.”

The day before we spoke, Jacobs posted on his Instagram the video from his February runway show, above the caption “mood as fuck” (since deleted). Held in the vast drill hall of the Park Avenue Armory, the show was the most personal, the most singular, in a career marked by self-expression. Jacobs worked with the choreographer and dancer Karole Armitage, whom he did not know before. He wanted to create something fun and nostalgic and, above all, urgent. At one point, 143 dancers and models moved across the floor, both apart and in serried groups—models flowing through dancers, dancers flowing through models, and everyone flowing through the audience. With Jacobs, it’s never about the fashion as such, though the clothes—plain and impeccable New York clothes—were fabulous.

“I feel like I still have stories to tell—I don’t know what they’d be right now,” he said. “But with that last show, almost unknowingly, I felt like I was telling my history of New York and what I had learned and my heroes. If this were my last show, I would feel that I had told my story thus far.”

As with every collection, fall began as a reaction to the previous one, with Jacobs talking with his closest collaborators, including the stylist Katie Grand and Joseph Carter, his director of women’s design. “We said, ‘How can we take the energy of the spring show but bring it back to gray, camel, black, with a bit of yellow, red, and blue—the three primary colors. So I made rules around the colors, and that was already a big hoop to jump through. There was plenty of room. So that was our minimalist reaction to the maximalist spring. And for spring, we had the whole group of models walk out—it was all these individual characters. It didn’t matter whether they were cisgender male, cisgender female, fluid. Body shape didn’t matter. We weren’t trying to be inclusive. I didn’t care. I just wanted to dress people who inspire me.”

Jacobs continued, “And then I saw that Karole Armitage had done a piece called Drastic Classicism. Then Katie Grand and I had a discussion about controlled chaos. All of these things that I kept hearing over the course of months, all these conversations—whether it was with Lana Wachowski, Sofia Coppola, Steven Meisel, or Anna Sui—all of them took me to this place of what New York is. New York, in my mind, is a really classic idea of fucking with the rules. And it’s also this unbridled urgency, and a sense of nostalgia, and our footprints, and our self–expression. I didn’t know how to tell it without someone else to take it past the idea of models parading around en masse. And I wanted contact with the audience—very important. I wanted all the people who were modeling the clothes to look at the audience. I learned that from Bob Fosse, actually—that it’s very disturbing to be pointed at or looked at, because there’s this distance that the audience has from the show.”

It was something Margiela had done in one of his early shows, as Jacobs reminded me: “He told the girls to look at the audience, and a kind of chaos ensued. People don’t know how to deal with that. They’re forced to meet what they’re looking at. It’s a great tension to break, but when that tension is broken and you’re delighted by it, you think, This is what contact is.”

At one point in our conversation, Jacobs said that maybe the best way to “fix” the fashion system is to simply acknowledge that high fashion is for a tiny elite audience—and treat it as such. To an extent, the industry has been doing this since the late 1960s, although the picture has become muddled in recent years as top brands load up their runways with commercial-looking clothes. At the same time, there is a squeamishness among brands to put daring or oddball design in its own category (unless it’s haute couture, which by definition is odd). They’d rather just throw everything onto a runway and let consumers figure it out for themselves. But it hardly promotes the quality that has always separated fashion from mere clothing—which is risk.

Jacobs said, “Why not show 12 party dresses in November? Whatever we might do will have to be communicated in a safe way and in some kind of non-live format. And who’s to say it can’t be 12 dresses? Or maybe it’s three dresses, two coats, and one suit. And we say, ‘That’s what we were thinking about this month, and if you order it now, you can have two fittings, and it will be available to you—made to order—in, say, two months’ time.’”

He got more animated as he spoke. “I’m putting the idea out there. Why can’t we restructure the runway? Let’s call it the way it is—it’s for a very few people, it’s out of very expensive fabric, and it’s very expensive to make. Let the prices and quantities reflect its rarity.”

I told Jacobs his concept made me think of a plain dark raincoat in his February show. It was wonderful.

“What you need to know about that coat—it was like a ’60s, very old man’s coat. You know, those very dark plaid, cotton balmacaans? Back in my day, in the ’80s, everyone used to wear them. Cecilia Chancellor—I always remember a couple of girls, we’d hang out at after-hours clubs, with our beers, on the rooftop, with the sun coming up, and everyone would have on these thrift-shop coats in very dark plaid.

“So what I did was send one of those coats to a factory in Italy, and I said, ‘I want to make this but luxurious. I want the outside to be this poor-looking cotton dark plaid, but I want the inside to be razor-cut double-faced wool.’ So it could be reversed or it could be this beautiful couture version of that very poor New York–style, grungy coat.

“It’s completely double-faced—there’s no interlinings or facings. It doesn’t have the weight of other clothes. If you saw the coat in real life, you’d see that there was so much more to it than meets the eye—in that, there’s nothing to it.”

When I spoke to Jacobs again in July, so much had happened—the protests and riots in response to George Floyd’s killing, the rage over systemic racism, the disturbing presence of paramilitary units in some cities, the tyranny of cancel culture—that it produced a jangle of new sensations on top of anxiety. But there was good reason to believe that things would change, at least in the industry. Many companies pledged to have greater Black and brown representation at executive and director levels, after decades of zero representation, and new groups like the Black in Fashion Council pledged to hold them accountable.

“I’m not a great teacher for this, but I do feel that I’ve had an awful lot of insight sitting in that room for four months,” Jacobs said, echoing a sentiment voiced by other designers as they emerged from their caves in Antwerp and Rome and Brooklyn.

I shared with Jacobs my sense that Europeans in the industry don’t seem to fully appreciate the level of rage here when he said, “What I’ve noticed when I speak to people in Europe is that they don’t see or feel what this feels like here. It’s been very weird. And I don’t want to be a privileged white gay Jewish New Yorker who is, like, ‘The Italians are racist and the French are racist.’ But it’s so clear to me that the effects of systemic racism and this system that we’ve operated in fashion are being felt much more in the U.S. than in Europe.”

Certainly one area where Europeans lag behind is cultural appropriation—that is, some designers still don’t get that it’s deeply disrespectful and ultimately a mark of Western entitlement. To them, it’s a matter of “creative freedom.” Jacobs himself was once called out for using woolen dreadlocks in a show (on mostly white models), and at the time he argued, naïvely, that it was okay since the style was part of rave culture. “I learned a lot from that,” he told me. “I do have creative freedom, but is that creative freedom operating responsibly in the world that we live in?”

Jacobs and I agreed on something else: The brands that put on digital shows for their haute-couture collections, in early July, would have been served if they had done nothing. The medium, the story lines, seemed not fully considered.

“Because the system told them they had to do something for that moment,” he said. “People wanted to operate in an old system, and then what you got out of a calendar was crap.”

“True.”

“And I have more questions about it—which is, who is it for? If it’s not for the red carpet—I mean, I understand the houses have couture customers who probably wear the clothes we never see on the red carpet, but then why don’t you just send images to them of what you propose for the season? You’re a couturier to a privileged customer. But once it lands on Instagram, I’m like, Who is this for? Where in the Instagram age does that live? Because it’s not exciting to see on Instagram. If you want to stimulate anger, if that’s the kind of response you want, then you got it. But I don’t think that’s what they were going for.”

Jacobs was as sanguine as he was in May, though perhaps less keyed up. He had left the Mercer and settled in a rental in Rye with his husband and their dogs. He confessed, “I could be here all the time.”

And he still did not want to predict what the future of dress might be post-pandemic (this fall, in lieu of a runway collection, his company will be offering items from the Marc Jacobs, a relatively new, less pricey label that repackages styles from the archive).

“There’s always that question—is fashion a mirror, or is it an escape? I think it’s both.”

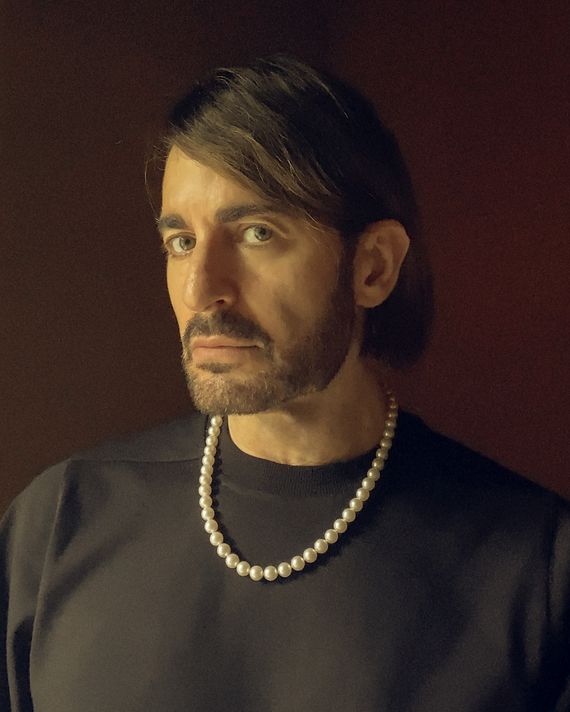

After a pause, Jacobs said, “When I went out for a walk, I didn’t go in jogging pants and sneakers. I wore a mask, but I got fully dressed. I had pearls on, I had a Celine blazer and Rick Owens platform shoes. If I had to go out for a walk, I’d put on my fanciest fucking coat, and I’d put on my highest goddamn heals. There’s nothing I’d love to see more right now than a girl, in full daylight, walking down the street in a sequined dress—just, you know, with a mask. I don’t really want to see a girl in a uniform. I want to see health workers in their uniforms, but I’d love to see these streets filled with people who are expressing themselves.

“I don’t want to see people conforming. I want to see people spreading their wings. And that’s what I keep trying to say with these posts. I’m spreading my wings. I’m painting my eyes, I’m putting on my heels, and I’m saying, ‘You know what? This is the world the way I see it, and I’m going to live in this world, and I’m going to go out with a mask on.’ ”

*A version of this article appears in the August 31, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

More From The Lost Season

- Miuccia Prada Is Too Wise for Post-Pandemic Predictions

- Stella McCartney Might Not Recognize You Anymore

- Reed Krakoff Is Looking for a New Design Language