On the first of April, a few weeks into our national confinement, Ina Garten posted a video of herself to her Instagram account mixing up a batch of cosmos. “You never know who’s going to stop by. Wait a minute — nobody’s stopping by,” she says in the video, her tone both stoic and wry. Into her shaker goes Grey Goose, the better part of a bottleful; Cointreau; Ocean Spray cranberry juice; and fresh-squeezed lime. (“It’s gotta be freshly squeezed. Very important.”) Without the hairstylists and makeup artists who prepare Garten for her TV show, she looks a little frizzier than we have come to expect, curls creeping into her trademark bob, and her usually chipper pronouncements have taken on a darker cast, even as her kitchen remains impeccable behind her, the toaster oven gleaming silver, the glass-front cabinetry conspicuously uncluttered inside. “You have to shake it for 30 seconds. You have lots of time; it’s not a problem,” she says, laughing, as if this were the only thing we really need to worry about, time. “During a crisis, cocktail hour can be almost any hour,” she adds, still shaking her mixer. She decants the entire batch, six to eight drinks’ worth, into a single martini glass that’s — no, it’s not a trick of perspective, it really is — roughly the size of her head and tips it, with some difficulty, back: “Delicious!”

The video was 80-proof Garten delight, and it exploded. Even for a woman who had been recognizably famous for decades as the Barefoot Contessa, cookbook writer, TV star, and all-around aspirational lifestyle icon, it was an unexpected surprise: a silly little bit, a kissing cousin of wine-mom comedy, but a balm. “Oh my God. It really did take on a life of its own,” Garten told me. It inspired parodies and homages; she was invited to re-create it on Stephen Colbert.

She understood the need for it. Since lockdown began, Garten had been holed up at home in East Hampton — working away, recipe-testing and filming, but without the usual team, doing her own camerawork on an iPhone, her own food styling, her own everything. “I almost don’t leave the property,” Garten said. Her beloved husband, known for his yum-yumming cameos, Jeffrey, was around but had rented a private office in town to work out of. “The virus is so scary that we’re incredibly diligent about making sure that we’re not exposing each other to it,” she told me. “We are of a certain age, unfortunately. So we have to be careful. I just think it’s too stressful to be out there.” They were admitting no guests, and even for homebodies like Ina and Jeffrey, the strain was starting to wear. Most days around five, they hopped in their Mini convertible and drove out to East Hampton Beach just to get out of the house.

It’s into this national mood of gloom and anxiety that Garten’s 12th cookbook, Modern Comfort Food, arrives this month. It might be reasonable to assume that Garten, like a meat thermometer stuck into our roasted country, cooked it up on the fly. But Garten’s brand has always been tipsy on comfort. In progress two years and turned in this January, the book was nearly finished by the time a national emergency was declared. Garten added a line about the virus to her introduction but otherwise didn’t have much to change; there were already recipes, updated for contemporary tastes (but really not all that much), for tomato soup and grilled cheese, beef stew, Boston cream pie. Which isn’t to say there wasn’t some strategic thinking there. “I knew that there was going to be an election a month after it came out,” Garten said. “And I thought everybody, no matter what side of the aisle you’re on, was going to need comfort food. Little did I know that at this point in time, it would be the, you know, the nexus of all of the race demonstrations and COVID and the election and all the stress that’s happening in the world — just extraordinary. Turns out we needed it more than ever.”

But will the rest of the food world agree? Like every other elite pastime, food media is currently confronting its many oversights, trying to bring in different perspectives, and acknowledging long-standing structural blinders. Garten is not about expanding our national palate. At 72, she’s a stalwart — hers is a time-honored formula in a rapidly changing time. Recommending her Modern Comfort Food, the New York Times felt compelled to couch its praise with a caveat: “The collection can seem awfully, well, Hamptons-y against the backdrop of more diverse offering this fall, but the spell Ms. Garten holds over her fans will not be broken.”

For all the upheavals and reconsiderations, Garten remains a figure of joy, a friendly, comfortable aunt whose fans — cooking along with her, gasping over her kitchen and garden — adore her. They feel they know her, too, and maybe want to be her someday. She cooks, but more than that, she calms. “I’m actually not that good a cook,” she told me, and like so many things she says, it both sounds like a line prebaked for the media but also, cozily, true. “I just work really hard at it.” Everything she does is doable, and she has coined catchphrases to remind you of it. How easy is that! At a time when ease is in short supply, Garten, as ever, is there to provide.

Garten is so inseparably the Barefoot Contessa that it’s easy to forget that she acquired the title — by way of a small prepared-foods shop in Westhampton Beach — in 1978, like a duchy in foreclosure. Many of those who revere Garten don’t know that the Barefoot Contessa, rather than Ina herself, was a 300-square-foot market, then a larger one in nearby, but fancier, East Hampton; Garten is our Barefoot Contessa now, emphasis on barefoot, and she learned her gospel of comfort at the old shop. (She sold it in 1996, and it closed for good in 2003.) “In the beginning, I was making all these complicated things, veal stuffed with prunes and Armagnac,” she said. “Nobody bought it. And then I started making roast chicken and roast carrots, and that’s what sold.”

She may be the local goddess of East Hampton, probably America’s toniest beach community, but her aura is that of an Everywoman made good, so relatable you might actually forget she’s not all that relatable. “It is kind of amazing, right?” said Deb Perelman, the cookbook author and blogger behind Smitten Kitchen, one of a legion of fans who have followed in Garten’s wake. “Because it’s not hard to really take a close look and be like, Oh my God, my life looks nothing like that.” Jeffrey is an alum of Lehman Brothers and Blackstone and a former dean of the Yale School of Management. They have no children but they do have homes in Paris and Manhattan as well as out east.

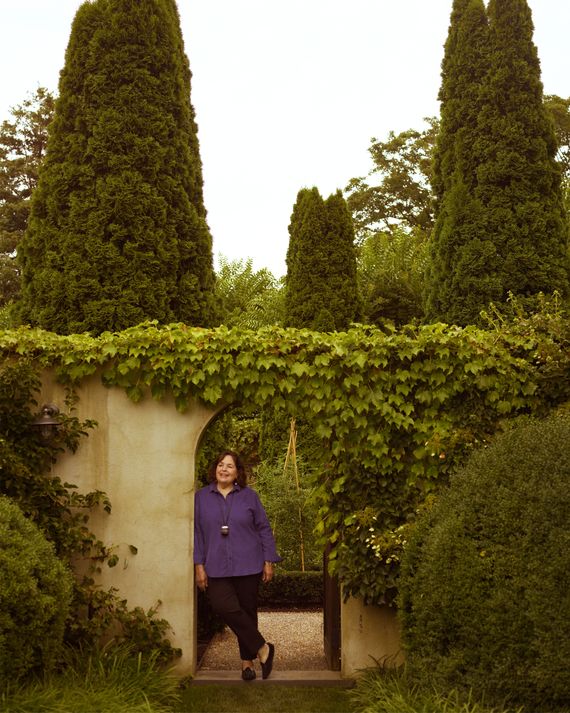

It’s tempting to imagine that Garten’s life is just a fantasy; it’s a fantasy, after all, potent enough that even the rich and famous, who can afford to do so, want to model their lives on it. (When 30 Rock’s Liz Lemon dreamed of summering in the Hamptons, Garten made a cameo appearance as herself, a benevolent neighbor bearing bruschetta and white wine; Nancy Meyers, a Garten fan, modeled the grocery in Something’s Gotta Give after the Barefoot Contessa shop.) In interviews, Garten can seem a paragon of almost unnerving contentment; a few years back, answering Vanity Fair’s “Proust Questionnaire,” she described her current state of mind as “It simply doesn’t get any better than this!” But Garten built this fantasy and now inhabits it. Her kitchen, famous from her long-running Food Network TV show, is housed in an ersatz barn on her East Hampton property. Every morning, she wakes up and pads across the lawn to work.

Garten’s mix of earthiness and grandeur, the way she promises that, if you can’t make some involved ingredient in one of her dishes, “store bought is fine!” while offering a glimpse into a rarified Hamptons milieu, has made her a great and durable success and a steady media-business model. All 11 of her previous cookbooks remain in print; in total, there are well over 6 million copies in circulation, according to NPD BookScan, which tracks print sales. (The publisher says the full number is significantly higher, but doesn’t comment on sales.) Her books come out on a cadence unusual even for industry stars: she has published one every other year for 18 years, each just in time for the holiday gift-giving. She’s the long tail of comfort cookery, and her first one, published in 1999, and her sixth, which came out in 2008, and her ninth, from 2014, have all sold roughly as well as each other. “There’s really no one like her in the category,” Aaron Wehner, her publisher at Clarkson Potter, told me. “I think it’s pretty hard historically to find an author who’s maintained that position for such a long time.”

Trends in food shift quickly, and last year’s star may not be next year’s. (How long has it been since anyone last heard a “Bam!”?) But the Pax Inana continues. New generations of food-media personalities have emerged, but rather than forsaking Garten, they’ve emulated her. Garten stays above the fray. “Kind of not so much,” she said when I asked if she kept an eye on the new guard. But they have an eye on her. It’s hard to imagine the “nothing fancy” ethos of Alison Roman without Garten’s unstuffy luxury. Garten and her recipes appeared dozens of times in Perelman’s early Smitten Kitchen posts, and Perelman freely admits she was inspired in her tone and presentation by Garten’s, whether she realized it at the time or not. Chrissy Teigen, who is building a cooking empire on the back of two books and a new web outlet, Cravings, is even more direct. Though one of her cookbooks playfully included a roast chicken “BTI” (Better Than Ina’s), the student acknowledges the master. “I don’t know if I would even — not just exist, but I don’t know if I even would have just started cooking without her,” Teigen told me.

Garten’s path to home-cook guruhood was winding — and, for her many fans, part of what makes her relatable. Born Ina Rosenberg in Brooklyn in 1948, she was the daughter of a successful surgeon and a homemaker who was, in Garten’s own estimation, an indifferent cook. “She wasn’t big on flavor,” Garten said of her mother, Florence. “It was, you know, broiled chicken and peas from a can. A very ’50s kind of cook.” Young Ina wasn’t allowed in the kitchen. “My mother always said, ‘It’s your job to study and my job to cook,’” Garten told me. She didn’t prepare a meal until she married Jeffrey Garten, a young Dartmouth student she met at 15 while visiting her older brother on campus.

Jeffrey went on to serve in Vietnam and collected a Ph.D. at Johns Hopkins. The couple eventually relocated to Washington, D.C., where Garten, who ultimately finished college at Syracuse, received an M.B.A. from George Washington University. Eventually, she arrived at the White House, where she worked as a budget analyst for nuclear policy at the Office of Management and Budget under Presidents Ford and Carter. “Washington was a great time,” she said. “You feel like what you’re doing is exciting, because it’s going to the president. But after a couple of years, you’d realize you’re writing the same issue paper over and over and over again, and nothing ever happens.” She looked at the head of OMB, a Cabinet-level position, and realized, she said, she was never going to be the boss — at the time, no woman ever had been. In the meantime, she had learned to cook from a Time-Life cookbook subscription gifted by her mother-in-law and from Julia Child recipes discovered in France; she and Jeffrey entertained often in Washington.

So when she spotted a for-sale ad for Barefoot Contessa in a newspaper in 1978, she drove out and snapped it up, even if she’d never been to Westhampton before. Her family was less than pleased. Garten’s grandparents had emigrated from Eastern Europe and accomplished the Jewish-American dream of upward mobility. “My grandfather owned a candy store,” Garten said. “And one generation later, my father was a great surgeon. He saw his daughter going to work in the White House, and then all of a sudden she’s going to own a grocery store. He was like, Wait a minute, we’re going in the wrong direction here.” Garten laughed at the retelling. “I had to really be sure to do it,” she said more seriously. “There were a lot of forces working against me. But fortunately, never Jeffrey.”

The shop was a success, and Garten moved it to the East Hampton in 1985. She feared resistance from locals, especially coming from the more downmarket Westhampton, but the shop flourished. “It was always busy,” said Barbara Borsack, a lifelong East Hamptonite and a former deputy mayor of the village. “There were always people in there, buying.” I asked Garten if her family eventually came around. “I think my father got it,” she said. “Many years later. But yeah, I don’t know. Who knows.” (Charles Rosenberg, her father, died in 2004; Florence in 2006.)

By the mid-’90s, after years of waiting on, and winning over, her persnickety neighbors, Garten was ready for a change. She sold the shop to the manager and one of the cooks and took a year off. “I couldn’t figure it out,” she said, “and just out of sheer desperation, I thought, Okay, everybody wants me to write a cookbook, I’ll write a book. And while I’m doing that, I’ll figure out what I’m going to do next.” She had the recipes from the store at hand, even though the publisher worried they’d be too simple to sell. Published in April 1999, with a foreword by Martha Stewart, a friend from the Hamptons, it was a hit right away.

A second book followed. Television was sniffing around: Garten taped a trial for a show at Stewart’s company, but it was quickly scotched. “They kept trying to make me into Martha Stewart, because that’s what they were used to,” Garten told me; they were horrified when she spoke to the camera with her mouth full. She had more in common with Nigella Lawson’s indulgent appetite than Stewart’s starchiness, and when Food Network came calling, it was a producer who had worked with Lawson who made it work. Garten planned to do one season; the show is preparing its 27th, tailored, as has become her habit, to her newest book.

Even more than the cookbooks, TV cemented her persona and even her look: Garten’s unchanging, untucked shirts have their origin in the early days of her TV show, when her director warned her to get a few copies of a few shirts so she could keep continuity if she splashed herself on-camera and had to change. (She joked that she now buys them “38 at a time” from Lands’ End.) Now she is instantly recognizable. Young women dress up as her for Halloween, and fans stop her in the street to tell her they should be friends. “There was a day that I was walking up Madison Avenue, and some woman in a big fur coat was like, ‘Oh, darling, just love you,’ and about a block later a truck driver pulled over and went, ‘Hey, babe, love your show,’” she said.

Is this real or apocryphal? It has the buffed sheen of an anecdote primed for the media, but Garten doesn’t carry the celebrity’s usual whiff of bull — you believe it, or you want to. “It’s very nice that people feel warmly,” she said. “I know that’s a real compliment. But I did have a TV producer who once said to me, ‘You’re the only star I’ve ever met that doesn’t want to be a star.’ I don’t. I don’t do this to be out there and to be well known. I don’t think anybody ever was made happy by being famous.” And yet she’s famous and famously happy. Soon you’ll be able to read all about it. Last October, after years of wondering whether anyone would even want such a thing, she announced she had sold a memoir, expected in 2023.

Having settled on her persona and her playbook years ago, there are things Garten will do and things that she won’t. Unlike many of her contemporaries, she is wary of licensing deals and collaborations. There were never Barefoot Contessa stores across the country, and there is no Barefoot Contessa cookware. There once was a line of Barefoot Contessa frozen meals — Garten swears they were very good — but the company that produced them was sold and she exercised her exit clause when a new owner didn’t meet her exacting standards. There was for a time a line of packaged baking mixes, but those have left shelves, too. You can feed your dog Rachael Ray pet food or dress your salad with Rachael Ray olive oil, paint your house in Martha Stewart colors, order her clothes on QVC, sip her wine, or dose yourself with Martha Stewart CBD, but Garten declines. There’s a laugh line she’s deployed over the years of being approached to market a fertilizer. Her delivery, as she repeats it to me, is perfect: “A fertilizer! You want me to put my name on your shit?” (Not for nothing has Garten won three Emmys.)

Politics is also off the table. “I don’t think that’s my thing,” she said. “I think my platform is about teaching people how to take care of themselves and the people around them, and I don’t want my politics to get in the way of that.” You could prod a bit at the Gartens’ circumstances and biography and make some guesses about their leanings — an Eater profile in 2015 delved into Jeffrey’s board memberships at Aetna and the Canadian mining company Alcan and joked (or didn’t joke?) that he was likely in the CIA — but Ina would just as soon you didn’t. She is no resistance hero, though it’s not hard to find her and Jeffrey’s donations to the Biden campaign and a host of Democratic candidates over the years. This September, she made an exception to her usual stance and hosted a virtual fundraiser with Jill Biden, promising cocktails and conversation for $250 a ticket. “I just think she’s a remarkable woman,” she said.

As the landscape of food has changed, Garten’s hasn’t — not much. From her first cookbook to her 12th, Garten has stayed in her own hedgerowed lane. “I don’t think the concepts changed that much,” she said, and she cooks from what she admits is a “very limited palate.” She prefers to cook in part based on her own memories. She gave the example of working on a recipe based on a charlotte russe, a kind of push-pop of sponge cake and whipped cream topped with a cherry, which was a New York sweetshop speciality in the early decades of the 20th century; she could remember having it with her grandfather in Brooklyn. “Those are classic American flavors — vanilla, cherry,” she said.

That’s a sentiment most younger food writers might be hesitant to say. Modern cookbooking is feasting on global perspectives: On Eater’s and Epicurious’s lists of fall’s most anticipated cookbooks, Modern Comfort Food is an anomaly, wedged between restaurant books and those dedicated to Afghani, Indian, Indonesian, Israeli, and African food. But Garten still makes the cut, year after year. I asked Perelman of Smitten Kitchen whether she saw Garten, whom she clearly reveres, as a benchmark to measure herself against. “A little bit,” she said. “Not in everything — I’m younger, and I think that my flavors, my interests are a little more diverse.” But what you can’t discount about Garten, she said, is that “the very center of what she does is write really good recipes that work for people.”

This is the practical essence of Garten’s appeal. “I have customers who say that all her recipes work,” said Bonnie Slotnick, the proprietress of one of New York’s best cookbook stores. “You don’t hear that about everybody, and certainly not all the Food Network frou-frou people.” Much of Garten’s effort is expended ironing out any possible kink from every recipe, down to how to slice every carrot or parsnip. She follows her own compass to the recipes she wants, and then tests and retests with her own team, rotating through two testing assistants, one who is a seasoned cook and one who isn’t. Behind the bangs and the telegenic chuckle glints the steel of perfectionism.

My own cooking falls somewhat short of this high bar, so I took the opportunity of this story to ask Garten to walk me through one of her recipes. She chose a mocha-chocolate icebox cake. I had gathered all the ingredients, which were Ina-ishly indulgent — two tubs of mascarpone, a pint of heavy cream, three bags of Tate’s chocolate chip cookies, and Kahlúa. At the appointed time, there she was on the computer screen, as seen on TV, in that familiar spotless kitchen. Together, we whipped cream and cheese into a thick, sleek icing and laid down alternating tiers of cookies and cream. The recipe had been inspired by an icebox cake, a mid-century staple with Nilla wafers, but Garten jazzed it up with cocoa, coffee, and cheese, Americana detoured by way of tiramisu.

Garten’s recipes are little fortresses, all but impregnable by error, which is of course the kind of challenge I like to rise to. I had made some assumptions that I assumed were harmless but turned out to be hapless: One does not substitute coffee for instant coffee, or chocolate-chip cookies with walnuts for chocolate-chip cookies without, and I caught a flash of the impatient steel beneath the cashmere of Garten’s mettle. “It’s funny,” she said, in a way that did not indicate it was all that funny, “I always say that people say, ‘Well, you know, your chocolate cake didn’t come out right. And what’s wrong with the recipe?’ And I go through the recipe with them and I find out that they didn’t have any chocolate so they used sardines instead.” She assured me that the recipe would still work, but not as she had created it. The Contessa’s life seemed very far away as I stood in my humble Brooklyn kitchen. The road to hell, paved with walnuts.

Nevertheless, we dolloped, and our cakes rose higher and higher in their springform tins until they were ready for an overnight hibernation in the fridge, from where it would emerge the next day plush and gooey and hanging together even when it seemed impossible that it could. I had not quite achieved the cheerful nirvana that Garten so effortlessly beamed, but it was heartening to think that my cookie-cake would be a little bit of joy and ease I could bring to a burning world, or at least my small corner of it. From her own kitchen, Garten pulled a chilled, rested cake out of the fridge — it magically appeared a moment after she put the one she’d assembled in, just like on TV — and showed me how to heat a knife under the hot tap to free it from its pan.

Our time was up; the program was ending, and there was plenty more Garten had to attend to. Soon, she would start her first virtual tour for Modern Comfort Food, doing Q&As with fans like Katie Couric and Jennifer Garner. Then it would be back to the kitchen in the barn, to keep testing and trying and finding the next recipe for the next book. But before any of that, there was Instagram to work on, and lunch to make, and a chicken to roast for dinner with Jeffrey, just as she does every Friday night. Labor Day weekend was about to begin, but Garten was still going, going, going. Comfort is hard work and big business, and while it won’t save us, we need it all the same: the cozy soup and sandwich, the cocktail hour. And she’ll do whatever it takes to give it to us, from safely above the fray. “I never leave the house so I have no idea,” Garten said, “but it must be crazy out there.”