As if on cue, three of the most prominent designers — Miuccia Prada, Nicolas Ghesquière of Louis Vuitton, and Virginie Viard of Chanel — aligned their visions with the entertainment industries. With one move, all three seized on the buzziest notions of the day: inclusivity, the feeling of public space, and celebrity. But it didn’t make for great fashion in every case.

Prada’s digital Miu Miu show looked and sounded like a sports arena, albeit a compact arena on, say, the International Space Station. Elliptical in shape, with white rubber walls and a grid-patterned floor, it featured a bank of screens with an ever-changing group of young and not-so-young virtual guests, sort of the Brady Bunch meets the NBA’s digital audience. Among the 60-odd guests were Chloë Sevigny, Beanie Feldstein, the Fanning sisters, and Miranda July.

Ghesquière took over the domed top floor of La Samaritaine, the historic Parisian department store, which, like Vuitton, is owned by LVMH. Department stores were at the intersection of fashion and mass culture in the latter half of the nineteenth century, and while their status has certainly taken a nosedive, along with malls, they still constitute public space and one-for-all shopping.

Viard, meanwhile, appropriated the Hollywood sign, or, at any rate, its symbolism, staging a live show in front of giant white letters that spelled out Chanel. Her predecessor, Karl Lagerfeld, was one of the first designers to recognize that people had no problem seeing fashion houses as cultural landmarks, and their merch as treasures, so why not copy the Eiffel Tower for the runway (as they did for fall/winter 2017)? Chanel also has a long history with film stars. After making costumes for three movies in the early 1930s, Coco Chanel found she had no taste for Hollywood’s packaged glamour. Her total confidence in herself is probably why so many of her ideas have endured. (Of course, she dressed actresses in real life.) And Lagerfeld dressed many stars for the red carpet, and once built a show and TV spot around Nicole Kidman.

Viard’s gateway, per her press notes, was the red-carpet photo-call — you know, that moment when a young actress stands a little awkwardly in her borrowed designer gown and jewels. To an extent, Viard conveyed the in-betweenness of adolescence and adulthood, between winsome (mock tiaras, a bubble-gum-pink cardigan and matching mini, a red sweater with CHANEL in pearls worn with black sequined petal pushers, logos galore) and sophisticated (a gorgeous, bare-bones tuxedo gown, a black mousseline number with poufs of black feathers). Unfortunately, the overwhelming impression was one of clunkiness.

The proportions of bouclé suits — worn with the extra burden of a waistcoat — looked jarring, the jacket and skirt (or shorts) slicing the model in the middle, like a magic trick. To further complicate things, Viard gave some jackets a hefty retro shoulder. Lagerfeld, in his day, was certainly capable of a stinker. (I recall a cone-shaped and quilted wrap that was a cross between a space blanket and a nun’s cap.) But humor was always his saving grace. It’s not easy to be light and funny, and Viard avoids it. Nor does she seem to have the confidence — or is it curiosity? — to play beyond certain stereotypes of women and girls. Also, if a couturier can’t make a pair of Bermudas look flattering on a model, she best not bother.

When you think of how relevant film — and art, generally — has been to fashion, it’s dispiriting to see such thin treatments. Probably it is a reflective response to social media and a culture that engages with a lot of stuff, and very quickly. Still, I was underwhelmed by Ghesquière’s Vuitton collection, especially after last season’s spectacular show. He focussed on gender for spring 2021, defined in his press notes as masculine and feminine, “a territory that is still stylistically vague.”

I would have thought gender the most explored, analyzed, transgressed territory there is in fashion. Ghesquière surely knows that, but if there are new expressions of gender to be represented, and there are, this wasn’t the show in which to discover them. However, Ghesquière kept to the familiar dialogue between men and women — the masculine coat worn with a cute, clingy minidress; the oversize parka with a mini covered in large, tawny sequins; the conventional pair of pleat-front khakis turned into sloppy, big pants and cinched with a wide belt and worn by a model of indeterminate gender. If anything was vague, it was his intentions.

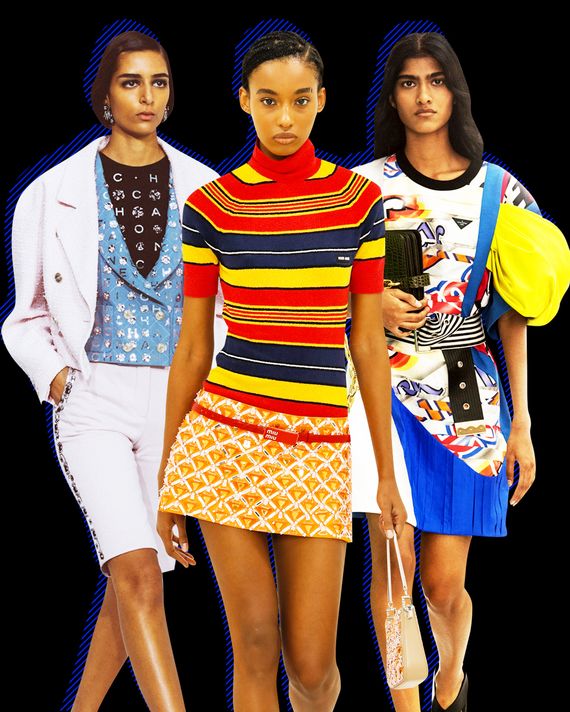

Oddly, Miu Miu also played with polarities. “These are polar times,” Prada said in a statement. Well, yes, but Prada had the good sense to confine herself to the crucial elements of fashion — cut, fit, newness. As a result, Miu Miu hasn’t looked this relevant in years. Although Prada did not work with Raf Simons on this collection — he only works with her on the main Prada line — Miu Miu has also set a new course. Gone is the tiresome kookiness of recent years. The label was originally known for its simplified silhouette, and a sweetness tempered by bad taste.

What really worked in the collection, what kept things clear and sharp, was the constant contrast in textures and patterns, from bold stripes to techno dots, and the electric colors ripped from cartoons, sports, and computer screens.

In short, a modern girl’s world. But what held it all together was the short, brisk silhouette.