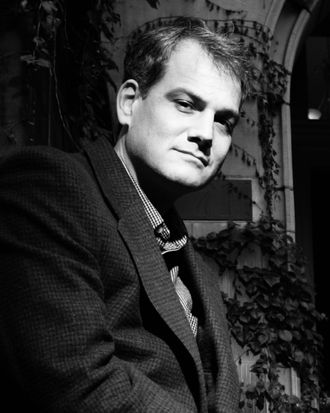

On Thursday, Eve Crawford Peyton, a former middle-school student of Philip Roth biographer Blake Bailey, published a gutting account of how Bailey, her favorite teacher and mentor, began grooming her when she was 12, then raped her when she was 22, in 2003. The article, which appeared in Slate, is a wrenching document: the chronicle of a man who gained power over vulnerable girls by behaving as if he were the only one who saw them as full human beings, but whose bone-chillingly coercive long game was in fact their dehumanization and objectification.

Among the most powerful moments in Peyton’s story is when she reads the account of another woman’s experiences with Bailey in a New York Times article published earlier this month. In it, publishing executive Valentina Rice claims to have been raped by Bailey on a night that the two stayed, separately, as guests at the home of Times book critic and former editor Dwight Garner in 2015. Peyton notes the horror she felt reading of an assault by the same man who had assaulted her, described by a woman she’d never previously heard of. “I put my head down on the table and cried,” Peyton writes. “I felt such agony for her. What if I’d said something back in 2003? Could I have spared her this experience?”

This self-recrimination, from a woman whose life was shaped both by Bailey’s mentorship and manipulation, feels unduly cruel because, in a way, that same Times story answered Peyton’s question: It is unlikely that speaking out would have spared other women, because 15 years after Peyton’s experience of assault, and three years after her own, Rice herself had said something. And no one had cared enough to actively pursue her allegations.

As the Times reported, in 2018, Rice sent an anonymous email to Julia Reidhead, the president of W.W. Norton & Company, which was publishing Bailey’s hotly anticipated Roth biography, telling them that Bailey had raped her and noting, “I understand that you would need to confirm this allegation which I am prepared to do.” According to reports, Norton not only did not respond to Rice or ask any follow-up questions but forwarded her email to Bailey, who recognized her and wrote her directly, promising that he would deny her allegations and begging her to stay quiet, invoking the harm her claims might do his wife and daughter, “who adore and depend on me.”

What has been on such gruesome display in the Bailey story (and so many others) is not the failure of individuals who have been harmed to speak up to protect others; it’s the broader failure of anyone in power to care when they do.

After receiving Rice’s email about having been raped by Bailey, Norton would go on to publish Bailey’s big Roth biography to great fanfare this month; it received mostly glowing reviews and quickly landed on the best-seller list; Bailey was profiled at length in The New York Times Magazine. Only a few critics — notably Laura Marsh in The New Republic — were bothered not simply by Bailey’s failures to interrogate Roth’s misogyny (long understood as central to his fiction) but by the eagerness with which his biographer defended it in his account of the author’s personal life. In the book, Marsh contended, Bailey sympathizes with Roth’s noxious view of his wives and girlfriends as objects for his enjoyment, women who become noisome when they do anything — argue with him, challenge him, ask him to buy a half a pound of Parmesan cheese for dinner — other than adore and depend on him. (Now, in the wake of multiple publicly reported assault allegations, Norton has halted publication. Bailey denies any wrongdoing).

Here are the confusions between cruelty and genius, the web of impunity and profit that conspire to not only let abusers off the hook but encourage them to benefit from their bias and ill-treatment of others. Roth’s attitudes toward women, on and off the page, have long been interesting to his fans and critics, an important element of his special genius; in turn, Bailey’s easy acceptance of those attitudes is what earned him his place as Roth’s biographer. As the Times critic Parul Sehgal pointed out in her review, Bailey has told the story of how he got the job: by bonding with Roth over a shared objectification of the actress Ali MacGraw. An important qualification for Roth’s biographer, Bailey had publicly acknowledged with this anecdote, was “not taking too prim or judgmental a view of a man who had this florid love life.” So it was Bailey’s willingness not only to not judge Roth’s leering but to engage in it in himself that made him the author’s chosen chronicler. And as such, he gained access: to the man, to his papers, to his memories. With that access and power came dependency: Norton needed Bailey, who had what the publisher needed to profit further from Roth, who of course had himself profited both despite and because of the retrograde attitudes that informed his work.

There was a blockbuster biography to be published, and in ignoring the rape claim made against Bailey, in letting him know that the publisher knew and would not be following up on it, Norton reaffirmed what a lifetime on this planet tells many men: that they will likely derive more benefit from mistreatment of women than face any repercussions for it.

It’s all such a revolting circle that it is a wonder that anyone ever bothers to speak up at all. The feminist critic Katha Pollitt recently wrote about a Zoom discussion hosted by the New York Institute for the Humanities at which Bailey spoke about his Roth book. Despite the group’s conversation having touched on the MacGraw story and Bailey’s amusement about the time Roth made an ex-girlfriend listen to him masturbate over the phone while she was at work, Pollitt writes, “No one asked a question that got within a hundred miles of women. I didn’t either. Sometimes I am tired of always being That Woman.”

But often, after the light changes and a whole pattern of cruelty and abuse begins to look different — bad in a way that it never has appeared before — women are told that they were not enough of That Woman: that they should have said something earlier, raised an alarm. I know how it feels to be sent this message after decades of hearing buzzing, screaming, hammering alarms go unheeded.

On the day that the Times published its first batch of reporting on Harvey Weinstein’s sexual predation in 2017, I wrote a piece describing how the movie producer had once publicly berated me, then a 25-year-old reporter asking him a question for a story I was reporting about his company. He had screamed vulgarities at me in the middle of a fancy book party filled with reporters; he’d tried to take my tape recorder away, his publicists trying to pull him away as he called me “cunt” and a cocktail party’s worth of people watched in horror. Ultimately, though the incident was public, reported in the Times, no one thought differently of Weinstein because of it. If anything, it bolstered his image as a tough-guy eccentric in the vein of the old Hollywood studio bosses.

History, even recent history, offers little promise that speaking up, making abuse public, will necessarily provoke censure or a rethinking of an abuser’s reputation. It offers a lot of evidence that instead, the abuser will continue to be lionized, until some ineffable moment at which their public history and track record of horrible behavior suddenly, and often only briefly, gets understood as a legitimately damning mark against them. The recent past also offers plenty of examples of how, for many, that ineffable moment of perspective shift will never arrive, no matter how many people tell their stories, no matter how public the bad behavior is.

A 1993 book about Donald Trump included his ex-wife Ivana’s sworn divorce deposition in which she claimed that he had once yanked out a handful of her hair and forcibly raped her; those public allegations (which Ivana would later walk back) did not interfere with Trump’s ascension in real estate, television, or politics. Sexual-assault allegations against Bill Cosby had been made public — in Philadelphia magazine, in People, on the Today show — for years before some switch flipped. In those intervening years, when the accusations were public but went largely unheeded, Cosby was fêted, celebrated, won an NAACP Image Award and a Kennedy Center Mark Twain Award, and got a deal to make a new television show.

In recent Vulture reporting on producer Scott Rudin’s violent mistreatment of his employees, one former executive described the comedian Chris Rock coming out of a meeting and joking to Rudin’s assistants, “You can relax. I know he beats the shit out of you.” Rudin’s behavior was never a secret, as the writer Michael Chabon, whose books Rudin adapted for film, wrote at Medium. “I regularly … heard him treat his staff … with what I would call a careful, even surgical contempt, like a torturer trained to cause injuries that leave no visible marks,” Chabon recalled, stating that he’d once seen Rudin throw a pencil at an assistant, hitting the assistant and then calling Chabon in for a meeting: “We started talking, as if nothing untoward had happened, about whatever script we were working on at the time,” Chabon writes, noting that “in those five words” — as if nothing had happened — is “the recipe for a culture of abuse, in families, in the workplace, and in the world.”

Two women have also gone on record accusing Virginia’s Lieutenant Governor Justin Fairfax of raping them, but it has not stopped his campaign, this year, for governor, a campaign during which he has felt comfortable describing himself as the inconvenienced and victimized party, comparing his experience of being publicly accused of rape to those of George Floyd’s, murdered by police in 2020, and Emmett Till’s, lynched in Mississippi in 1955. Despite a decades-long reputation as a vindictive and abusive brute who has made crude jokes about women in front of cameras, Andrew Cuomo remains the popular governor of New York; he has recently been accused by Charlotte Bennett and other women of sexual harassment and assault.

The world that treats power abuse, harassment, bullying, racism, and assault as if nothing had happened, especially when weighed against remunerative work, adoration, and the further accumulation of authority — the making of a movie, publication of a best seller, the election of a politician — is a world that confirms over and over and over again that bad behavior is imaginatively linked to power and profit.

The post-Weinstein years should disabuse us of the fantasy that we can make systemic correction simply via individual testimony and individual repercussions — the bravery of a few truth-tellers, the punishment of a few bad apples. Because for all the Me Too era promises that the systemic rot would never again go unseen, recent events confirm that this goes on unabated, all the time. Institutions and individuals were supposed to know better, but they do not. Or they do. They just still don’t care enough to let it interfere with their profits and their power. None of this has ever been about individual responsibility or culpability. It’s about our decision to keep living as we have been, to keep associating genius with abuse, status with merit, authority with impunity. It’s about the collective decision we make, again and again, not to care enough to act, not to care enough to change.