In the world of Joss Lake’s queer, synesthetic, dystopian novel Future Feeling, avocados don’t have pits and an Illuminati-type trans council undercuts nefarious capitalist influences by teleporting sexy, stern angel-mentors to fix problems. Everyone’s spiritual state is highly surveilled and fantastically color-coded: “A Bio-meter would have beamed marigold with ‘social-justice-related awkwardness.’” Subway cars glow the amalgamated color of their passengers’ moods. Emotional frequencies are of the utmost importance. And all of this feels as accurately expressive of my own brain’s worldview (feelings! Colors! Queer stuff!) as anything else. I say this to Lake over a video call, and he nods like he’s giving himself and everyone else permission: “You don’t have to stay in the social-realist world.”

And why would we?

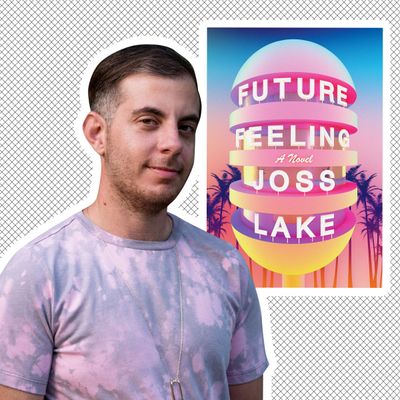

Future Feeling’s title announces the formidable force that emotions hold in this futuristic world. The novel triangulates among three trans men caught in a dangerous loop of ruining one another’s emotional landscapes. The sickeningly spiritually aligned Aiden Chase is so discriminating he has a pet goose; his posts on “the Gram” are idolized and reviled by disgruntled dog-walker Penfield R. Henderson, who tries to use his beloved aloe plant Alice to curse Aiden. Instead, the hex ricochets onto Blithe, a sensitive and apprehensive writer. The Illuminati-esque trans society rounds up the myopic troika to disentangle the mess they’ve made of one another. It’s a party: one grump, one Adonis, one introvert, each with another’s fate in their hands. There’s romance and sex in Future Feeling, but, boldly, its central relationships aren’t between lovers or really even friends. The book prioritizes relationships that aren’t categorized so easily.

“Transitioning is not moving through time in a linear way,” Lake says to me, from his apartment in Ridgewood, Queens, on a summery, stormy midday. “If you’re moving through these developmental stages in a non-linear way, what are the dangers of thinking someone else has it figured out?” Future Feeling sets out to answer this question, capsizing the very ideas of queer admiration, envy, and aspiration along the way. These tethers of connection to people we admire feel crucial — but because they can be tied to distant, idolized strangers, it can seem absurd to admit their importance. By bestowing slight moments with devastating fracas, the magical realism of Future Feeling makes these ties as ropy and strong as they feel. Like 94 percent of real life, it’s high stakes and big feelings about minor-seeming stuff.

With its glowing train cars of commuters and accursed social media posts, Future Feeling physicalizes the private projections, yearnings, and jealousies of people who are strangers to each other. A rogue coy brag sends one man into a nearly irrecoverable fixation; a petty, vengeful jinx dooms a bystander to psychic ruin. No interaction is safe from unintended consequences, and relentless positivity is a fair target. Goose owner Aiden posts constantly with outrageous self-actualization: “I am always replenished when I get to bathe in the hum of New York. Sending muscular love and light.” Pure, villainous self-assurance. But of course, Aiden’s not a villain. He has his own flaws and falters. The book leaves no idol uncomplicated.

Flamboyant surreality seems inextricable from Future Feeling’s thematic purpose, but Lake tells me that the first draft was fairly realist. “My aesthetics, before transitioning, were very much aligned with the imaginative,” Lake says. “When I was transitioning, all my attention narrowed to these everyday experiences.” Day-to-day activities felt newly fraught. “I felt really sucked in this confined way of looking at things: How are people judging me? How do I do X, Y, and Z now, in this new form I’m in?” Only after settling into his new form did he begin to regain access to creative surreality again. “Magic just returned to me, of course, to explain the complexities of our world and possibilities that may not be present at the surface.”

Maybe the largest fantasy in Future Feeling concerns the health-care system. Lake’s vision of a care-giving trans secret society soars: “In the recent past the queer child of a billionaire had started funding the Rhiz, and so the network could jet Operatrixes around and pay for surgeries and offer health insurance.” Rhiz’s Operatrixes are like divine, principled apparitions who come to solve problems. They take different forms; Penfield’s first Operatrix is tall, “a hybrid ghost of Kathy Acker and a 1920s ‘new’ femme.” I spent the book waiting for new ones to arrive and was never disappointed.

Lake, unsurprisingly, has dabbled in creative healing experiments himself. Since 2019, he’s run a literary sauna series called Trans at Rest, inspired by a trip to Spa Castle he took around the time he started transitioning in 2018. “I went there to relax,” he laughs bitterly, “but I was so tense because it was so gendered.” He tried to win a grant to bring other trans writers to Spa Castle, but the project was rejected over fears that the organization would fund something that might result in the participants being harassed. Cue a deus ex machina: “It just so happened that my friends had moved to the Rockaways. She and her partner and the people who own the space just happened to build a private sauna at the same time I was turned down. She’s Finnish, she’s very much about spa culture,” explains Lake. So the following spring after the trip to Spa Castle, Lake invited trans writers there. They soaked and steamed, wrote, and read their work. The series has continued — albeit on Zoom, with a virtual sound bath last year — but its power to decompress remains. “People did come away refreshed.”

We’re only a breath away from “Always replenished when I get to bathe in the hum of New York. Sending muscular love and light.” But despite Future Feeling’s slight polemic on seeming gorgeously admirable, it doesn’t doubt that some people are great to admire. Lake’s leadership positions — with Trans at Rest and also teaching writing for places like the School of the New York Times and Catapult — shifted his position on mentorship. “It’s definitely something that has evolved for me because, at my starting point, I was idealizing other people, whether it was the queer community when I was younger or in grad school,” he says. “Now I try to think a little more horizontally. How can different relationships support each person and co-evolve? It doesn’t have to be a hierarchical reproductive system where someone mentors you and you mentor someone.”

It’s great to have people to admire — people are cool! — but Future Feeling proposes that if there’s anyone you’re looking up to, they are occupying a magical, invented realm, to some extent. “If there are people I am looking to aspirationally, how can I also acknowledge their humanity? There will be certain things they don’t have figured out,” Lake says. “I find a lot of relief in puncturing the idealistic view.”