Over the years, memes have evolved from their broad relatability and humble top/bottom text origins to become absurd, esoteric, and often dark. They’ve been used since around the mid-aughts to convey feelings around mental illness, particularly anxiety and depression, but fears that memes may “romanticize” mental-health issues still abound. For many, though, having painful or shameful feelings validated can be a form of cognitive reappraisal.

The memeification of serious mental-health issues like addiction and trauma can be even more controversial. We understand memes to be jokes, but culturally we perceive some things, like trauma, as too serious to joke about. Of course, trauma is serious, and its effects on the brain and body are extensive and unpredictable. For many meme creators and trauma survivors, however, that doesn’t mean it’s off-limits for humor.

Instagram accounts like @69possums420 and @binchcity that deal with trauma, therapy, and healing through memes may be confusing for those who either haven’t experienced trauma or are earlier in their process. But healing, like all things, takes different forms for different people, and creating memes is not mutually exclusive to therapy.

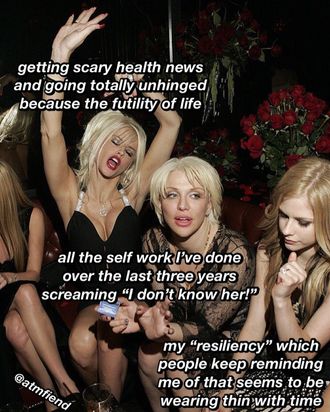

Erin Taylor, a writer and artist whose upcoming book of poetry is titled Bimboland, is a trauma-meme trailblazer. She started @atmfiend as a way to explore topics like sex, kink, and vulnerability while working at a sex dungeon, but it has developed into an artistic practice and “interactive trauma diary,” she tells the Cut. True to form, the account feels at once voyeuristic and reassuring. Images of everything from celebrities to Sopranos screenshots to Taylor’s own selfies are overlaid with text that can feel jarring. In one, teddy bears hug beneath bold pink text that reads, “I was raped this summer and all I got to show for it is an inability to have healthy relationships.” In another, a family holds a baby’s stroller on the rail of a bridge, and the overlaid text references the complexities of familial abuse. Recently, Taylor has been grappling with a serious medical diagnosis through the art of memes.

It’s that hyperspecificity and candor that makes @atmfiend and similar accounts unique, even exclusionary, but it’s also what makes them communal. The format is an invitation to relate, destigmatizing topics that people find untouchable. Taylor tells me that when she started making memes about child sexual abuse, she rarely saw anyone else doing it but that she soon found solace in the practice. “Certain trauma carries a lot of taboo, and this kills people because it’s so easy to internalize the stigma,” she says. “The more you talk about these things openly, it becomes clear that you’re not alone and decreases the overall shame. But even more so, it allows survivors agency over their own narratives.”

Trauma memes work in the way that all memes do — they communicate something instantly recognizable or relatable — but there’s an extra level of understanding for both creators and audiences. Clinical psychiatrist Vincent McDarby believes trauma memes can aid in healing and help people learn to encounter their triggers without being overwhelmed by them. “Processing is about being able to experience these emotions at a level we can tolerate. If the trauma evokes such a strong emotional negative reaction that we’re overwhelmed, we’re not able to heal,” he tells me. “Memes can be one way of trying to process the emotion.”

Several trauma-meme creators agreed that processing traumatic experiences is complex but that you can really begin to do so only by confronting them. Artist and writer Aiden Arata (who is in a “meme group chat” with Taylor) creates and posts memes about topics relating to mental health. While some are more absurd and some more relatable, many deal with the process of healing. “I started making memes because I was unwell,” Arata jokes over email. “Metabolizing difficult experiences through art has always felt natural and healing to me; you can exorcise that part of yourself and examine it from a safe distance, give it a purpose to get some sense of agency and meaning back.”

For Arata, the joy lies in using humor to reclaim experiences that once felt shameful. “Remember when it was okay for dudes to tell rape jokes? That was not that long ago!” she says. “Reframing trauma, taking the predator out, revisiting the experience with support, and exploring the perspective of someone who wants to heal is appealing because it makes this terrible, giant thing feel valid and real and also like something you can actually get over.”

Many people are squeamish about the idea of joking about trauma, including consultant psychiatrist Dr. Chi-Chi Obuaya, who believes humor is a “defense mechanism,” a way of deflecting a triggering situation. “There’s definitely a rationale to using humor,” he says, but it’s “potentially unhelpful” because “there’s a degree of sensitivity around traumatic incidents.” He worries that they may trigger others.

But McDarby disagrees and believes that humor is a valid way to seize control. “To be able to laugh gives us a sense of agency and control over our emotional reaction. Especially if it’s something that has always given us a negative reaction. If talking about a trauma or addressing it in any way makes you angry or upset or scared, it’s controlling you.” Perhaps, too, demarcating certain topics as nothing to be laughed at can be harmful and add to a culture of stigma and silence. The power of trauma memes lies in subverting that, in refusing to be silent and instead laying bare and laughing at the most painful parts of human existence.

Validation, now an online buzzword, is still a powerful tool in healing, and on meme accounts, it works both ways; creators share their experiences and affirm those of their followers. “It’s incredible to have weird or shameful experiences or parts of myself validated by thousands of people,” says Arata. The format also isn’t as unlikely as it at first appears: “Trauma resists narrative; our brains literally don’t create traumatic memories the same way as ‘normal’ ones, and we store a lot of that information in the body in ways that feel irrational,” says Arata. “There’s something about the image-text relationship, the immediacy, and the non-definability of memes that reflects some of the ways traumatic experiences play out on our subconscious.”

Some people struggle to parse darker humor in all its forms, but in the case of trauma memes, this seems like a fundamental distrust of a modern form. Nik Slackman, a priority research scientist at the Bard College Meme Lab, tells me, “As a Zoomer, I cannot remember a time when digital content was not being used as a coping mechanism. I think these pages are vital for destigmatizing scarcely discussed topics, not only by publicly speaking about traumas but by directly influencing the ways in which people joke about and discuss these topics in private. These pages provide material for casual but crucial discussions within established IRL communities.”

The coronavirus pandemic has left people worldwide without access to their usual support systems. Demand for therapy has gone up, but access to formal support can be hard to come by in many countries and people are left finding new ways to cope. “Over the past year, due to the stress of the pandemic and all that came with it, combined with a forced loneliness and reflection, many people have started accepting and recognizing that they actually have a lot to heal from,” says Taylor. Memes can offer a genuine space for healing, from both trauma and just the chaos of being alive. As Arata puts it, “In 2021, everyone has a deeper personal understanding of physical fear, of hopelessness, of grief, etc. We need memes to deal with that.”