My 7-year-old goddaughter missed her friends a lot over the past year. Like most kids, she spent the pandemic indoors and, as an only child, mostly without the presence of other children. A deeply inventive and wildly creative child, my goddaughter had tons of fun inside, largely due to the fact that her parents have the patience of saints and gave her space to explore her interests, some of which include: experimenting with outfits, making tiny people out of rocks and sticks, doing an intense inventory of the world of Pokémon, participating in her first school play via Zoom after the kids did everything from creating the characters to writing the script, and smearing her face with lipstick while demanding to be told the history of strawberries.

But she still missed her friends. Like the majority of children — and a healthy percentage of adults — I know, for her, Zoom dates quickly turned to tears as she realized it was a withering replacement for the fun and excitement of shouting with your best friend in the same room.

When my goddaughter finally got to see one of her friends in person, her mother — my oldest friend — drew chalk circles in the driveway for them to stand in, far enough apart to avert risk but so painfully close it made each child cry to not be able to hug each other. When she texted me photos of their reunion later that evening, we thought about how our own parents would handle the situation and laughed, deciding that they would have left us outside to fend for ourselves, pandemic be damned — they had a baked ziti in the oven and long, cord-stretched phone calls to make to each other.

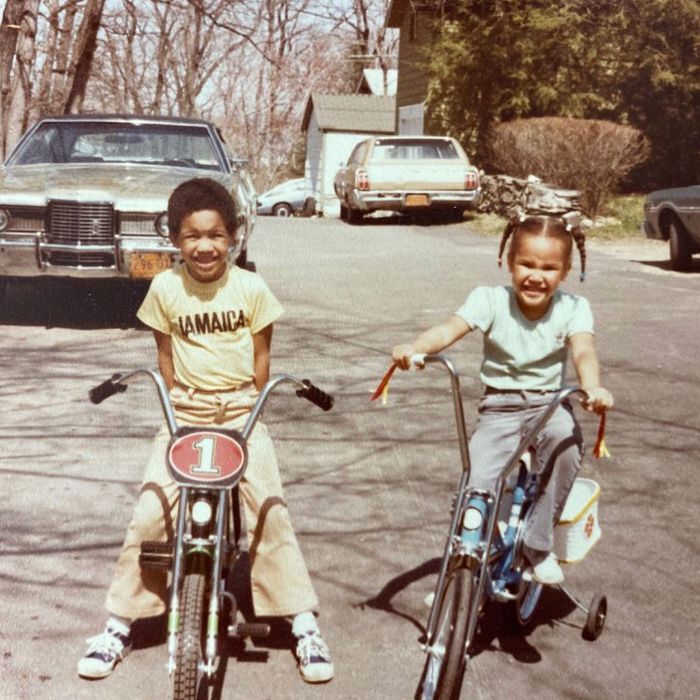

The hardest thing to convey to the children in my life about my childhood is the concept of unadulterated freedom. As people who have been scheduled and monitored down to the second for most of their lives, they truly cannot conceive of life outside of the panopticon of their own experience. When I was a child, a successful day was one where I saw my mother for two hours total, split evenly before and after she went to work.

Helicopter parents were born in the 1980s, a direct response to their personal experience of being roundly ignored by their own parents. Children were not to be seen nor heard, and we were definitely not supposed to complain about any injuries sustained during the 15 hours a day we roamed the streets. We saved popsicle sticks from the Fat Frogs, Rocket Pops, and assorted ice cream purchased at the Good Humor truck to fix our sprained and broken digits, taping them to our misshapen fingers and toes with contraband masking tape snuck out of a kitchen drawer while someone’s mom watched Days of Our Lives in the living room. Mosquito bites were relieved by using our fingernail to press a cross shape into the swelling skin, bee stings were only an emergency if they caused our throats to swell so much we could no longer call out “Marco!” or “Polo!,” and the only antiseptic liquid used on cuts and scrapes was our own spit.

The 1980s were a decade of neglect, and I haven’t felt freedom or terror like it since.

As an indoor kid at heart, it took me a while to warm up to being outside all day every summer. I could easily fill an entire day reading library books, creating new outfits for my Barbie out of candy wrappers, or practicing crochet chains with the giant ball of yarn my grandma gave me. Inside was full of wonder, mystery, and the life of the mind. Outside was a hellscape of insects, rusty nails, and scraped knees.

But the outdoors offered something that was hard to find inside the two-bedroom apartment I shared with my mom and brother: freedom. I craved the freedom that came with extended summertime parental neglect. Parents worked all day or had household chores we were never privy to while we were in school. The further out of the way we were, the better. We formed friendships out of necessity, banding together for survival. With my only company being other children, I quickly became accustomed to a more feral way of life.

We learned how to read a clock in school only for it to immediately become completely irrelevant; we rose with the sun, like farmers, and came in for the night when the streetlights turned on. The more ambitious among us laid out their play clothes the night before so they could jump into their outfits like firefighters ready to tackle a blaze. The truly epic slept in their filthy clothes after a night of arguing with their parents about when it was time to come inside in the first place.

Summers in Greenwood Lake were wild. I lived in a part of upstate New York that was more country than suburb, a town with one stoplight and no signs indicating “Children at Play.” Not only did Mom avoid scheduling any day camps or babysitting, but she also had no earthly idea how my brother and I spent our time once she left for work. She once came home to a pile of burnt matches on the doorstep where my brother and his friends used a significant portion of the afternoon trying to light the side yard on fire, and she was only angry that they didn’t clean up after themselves. The one true rule of summertime was that we were not allowed in our own house until she came home.

“Do not run in and out of this house all day with your friends,” Mom said sternly. “I don’t want you in here ruining everything.” It was never clear to me what we might ruin or how we could ruin it since we had to ask her for permission to play with our own toys, but in Mom’s mind, any child left alone in a house for more than three minutes was looking for an excuse to rip couch cushions apart with their bare teeth.

My internal clock was never keener. Without arranging to meet, all the kids in a two-mile radius managed to wander out to the yards and streets of our neighborhoods around the same time each morning like Raisin Bran–fueled zombies. Sometimes you would hear a kid outside playing before anyone else, and that would be the clarion call to the rest of us to hustle. A cacophony of banging screen doors signaled our mass exodus. We were wild. We were free.

Mostly, we were heathens who urinated outside for months.

Staying outside all day meant we had to find ways to be resourceful about the lack of a toilet almost immediately, and the biggest daily grift was trying to weasel your way into a bathroom. Any bathroom. Stay‑at‑home moms everywhere lived by the same credo: No Child Left Inside. Sometimes someone would summon the courage to knock on a door and ask. The mom would answer and narrow her eyes suspiciously. “Number one or number two?” If it was number one, she’d just shake her head. “Outside,” she’d say, pointing into the distance. “Can’t have you kids running in here all day.” If it was number two, she asked the cruelest question of all: “Can’t you just hold it until you go home?” Even if your guts felt like a freshly wrung T‑shirt, you instinctively knew that the answer was yes. It took a real psychopath to ask that question, and a real sociopath to say no.

Wildness can exist indoors, but it’s not as fun. As latchkey kids, my brother and I had to entertain ourselves for hours before my mom got home from work, which generally resulted in some form of shoulder-high mayhem. The crowning example of this would be the creation of Spiderweb City, which we achieved by ransacking Mom’s yarn basket, tying a loose end to a piece of furniture, and running around the room looping the yarn to furniture, shelving, and window latches until the entire space looked like that parkour theft scene from Ocean’s Twelve. Once she was able to slice and hack her way inside, Mom was furious. I spent the cumulative equivalent of entire days pressing my nose into various corners of our apartment as punishment, but I was never grounded for anything I did outside of the house, where, for example, I routinely lit things on fire. Indoor creativity pushes the boundaries of parental patience far quicker than outdoor wildness.

In the past year, as we received the indoor-kid dream directive to stay inside, I’ve never felt lonelier, less focused, or more anxious. I daydreamed about feeling soft grass on my bare feet, walking down the street with another person, or, if I really let myself go, cracking open one more bottle of wine on someone’s porch while the moon clocked in for its regular shift. I’ve started to look back on those childhood summers with more fondness, making promises to my future self that I would recapture those fleeting moments of freedom whenever possible. I haven’t examined it closely, but this is surely part of the reason I recently purchased my first home, a farm, and immediately set up an archery range on the back acre of my property. I want enough space to roam with my friends. I want the night sky. I want to get poison ivy, I want to get sprayed by a skunk, I want a thin film of dirt winding toward the shower drain at the end of a long day of nothing.

I’ve watched enough true-crime documentaries to want to keep my goddaughter heavily chaperoned until she turns 50, but after the year we’ve all had, I hope there’s some room for kids to take a cue from the 1980s and explore this summer. To break free of their chalk circles and find a place in the yard to squat, just out of view, and mark their return to the world.

Excerpt is adapted from Danielle Henderson’s The Ugly Cry: A Memoir

Every product is independently selected by our editors. Things you buy through our links may earn us a commission.