In the middle of the N train on the last Saturday night in June, someone in a crop top was shouting to the riders like a subterranean town crier: “Stay hydrated and carry Narcan! Check your shit!” Partying in New York was back for Pride weekend, but with an asterisk: Be careful with your drugs.

For every DJ set on offer, bars seemed to be holding training sessions on how to administer Narcan, the nasal spray that can reverse opioid overdoses. The host of a house party I went to in Chinatown dutifully informed her guests that the Narcan was located in the kitchen should anyone need it, as if she was pointing out the bathroom. At a daytime event at H0L0, a music venue in Queens, a harm-reductionist named Dave Justice gave out his last test strips, pieces of paper that can be used to check injectables, powders, and pills for the presence of fentanyl, the extremely potent synthetic opioid. Though illegal fentanyl is overwhelmingly responsible for accidental overdose deaths involving heroin, Justice explained that attendees were specifically worried about fentanyl and cocaine. “Someone overdosed on some fentanyl and cocaine out in Brooklyn a couple weeks ago,” he said. He had heard it was a person “core to a bunch of different friend groups across Brooklyn,” but knew nothing more.

That’s about all I — or anyone — seemed to know, even as the idea that “there is fentanyl in the cocaine right now” has crystallized into a kind of emergency common knowledge, shared confidently among a certain class of New Yorkers reemerging into the city’s nightlife.

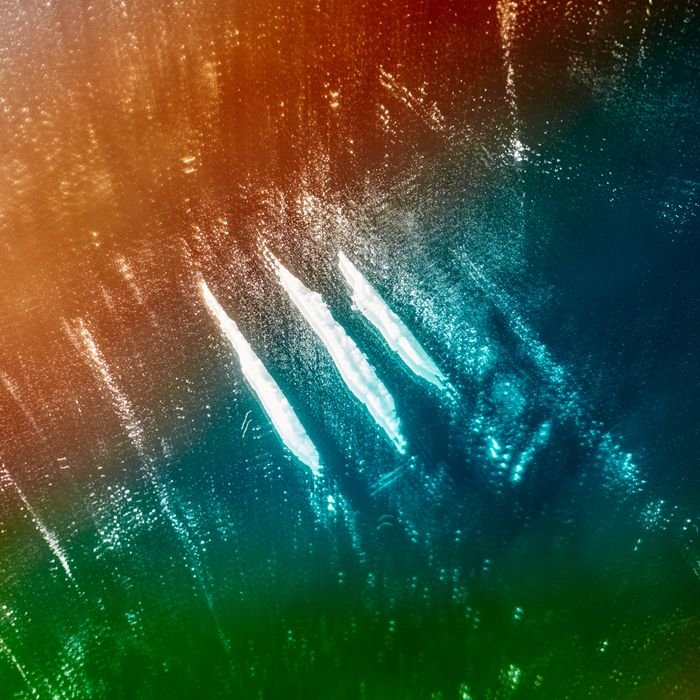

Reports of cocaine-overdose deaths in Brooklyn first circulated on social media in late May, though the word “reports” makes the information sound more official than it was. “Community posts” would be a more accurate description — announcements made by various sections of a Venn diagram of young, art- and media-adjacent social circles. “There’s fentanyl in the coke going around in Brooklyn and Queens,” a podcaster and comedian tweeted on June 25. “Someone died in Ridgewood. Please be safe out there.” He was retweeted 3,000 times. The same day, a writer shared that there “keep being reports of bad coke with fentanyl in it around nyc,” with more than 8,000 retweets. On Instagram, an account with the handle @hilovenewyork posted a screenshot of a disturbing text: “My friends died last night from bad coke, multiple people,” it read. “Please let your friends know.”

This same handful of tweets and screenshots quickly traveled to the blog Bushwick Daily and to Gothamist, which reported that it had tracked down the name of one of the people referenced in @hilovenewyork’s post. A friend told the outlet that “after doing cocaine, the person had been found dead by his partner in their home early last Sunday morning.” Though the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner said that a cause of death had not yet been determined, the incident was already ballooning into a scare. Panic reached the Daily Mail on June 3: “Cocaine laced with fentanyl ‘is wreaking havoc on the NYC club scene with at least two people dying from overdoses.” It referred to an oft-quoted NYPD stat regarding cocaine overdoses and fentanyl: 8 percent of cocaine in the city had allegedly tested positive for fentanyl in the month of April, or one out of ten bags. The paucity of information, rather than breeding restraint, fueled paranoia: “Police refuse to reveal how widespread the tainted supply is,” the Daily Mail read.

By now, at the height of summer, Instagram infographics about naloxone — the chemical name for Narcan — are pinging around Brooklyn the way posts about the merits of double-masking were six months ago. I have heard from at least three friends that some of their friends have recently died of accidental overdoses but have heard no details; I’ve passed along the warnings anyway. One person who lost a friend in New York within the past several months to an overdose told me that members of his social circle have all started carrying Narcan and test strips, “because of all the bad news.” He was laying off cocaine for the time being — as best as he realistically could. “I’m not a Puritan,” he hedged. “Sometimes, if it’s available …” But even this person doesn’t know how much truth there is to rumors of a widespread “bad batch” or something “going around.” He’s not sure how worried he should really be. “I don’t know if it’s just a few anecdotes in a similar social group,” he said. “Better safe than sorry, right?”

Reporting on drug use, as a frustrated peer of mine put it (another person who lost a loved one to an overdose in the past two months), is almost purely anecdotal. Even in 2021, with more attention than ever on the overdose crisis, all you can do is ask around. And the people who will talk don’t want to go into specifics — out of fear of prosecution or of offending the family of the dead. Most often they don’t know exactly what someone was taking or what killed them.

Even the city officials most equipped to know what is going on are in the dark. Data on overdoses, tracked and disseminated by the New York Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (or DOHMH), is collected from the DOHMH Bureau of Vital Statistics, emergency room visit information, and the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME). These sources can be problematic in a few ways. OCME data, for example, comes after lengthy toxicology reports are undertaken and can have a lag of up to a full year, according to a spokesperson from the Health Department. And that was before the medical examiner’s office was inundated with bodies of New Yorkers who died from COVID-19. Though 2020 is expected to be the worst year on record for overdose deaths — more than deaths from suicides, homicides, and car accidents combined — officials say they are still waiting to finalize numbers.

From the information it does have, DOHMH confirms that accidental cocaine deaths involving fentanyl have been steadily on the rise, in line with national trends — with some important caveats. Though fentanyl had been intermittently present in the New York drug supply, the Health Department noticed an increase in fentanyl-related overdoses in 2015. Within two years, fentanyl had become the most common substance in accidental drug overdose deaths in the city. Overwhelmingly, fentanyl is present in accidental overdose deaths involving heroin, because it is often sold as or with heroin. Drug suppliers cut fentanyl into heroin in order to make more product at a lower cost. But because people frequently consume cocaine and heroin together on purpose, separately or combined in the form of a speedball, it can be difficult to figure out exactly what caused an accidental overdose death and therefore to disaggregate overdose data along substance lines.

According to DOHMH data, overdose deaths involving fentanyl and cocaine (but not heroin) began to spike in 2016. “When it was first identified it was relatively infrequent,” Michelle Nolan, a senior epidemiologist at the Department of Health told me, but DOHMH data for 2016 shows a jump of over 100 deaths from previous years. Advocates and harm-reductionists with street-outreach operations report the same increase, with users recounting more fentanyl-related overdoses involving stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamines in the past three or four years. Rachel, an artist, writer, and sex worker who withheld her last name, began buying Narcan and test strips in New York around that time, after she had seen people testing their own drugs in European clubs and bars. The more her friends tested, the more they found positives for fentanyl. “They’re just always floating around my purses,” Rachel says, of Narcan doses. Justice, the harm reductionist, who also works on the Lower East Side, said dealers of all kinds started coming in for test strips — to check their own product themselves — last summer.

As for this summer’s alleged spike, Nolan (from DOHMH) couldn’t conclusively say. The Health Department monitors emergency-room overdoses, but they don’t release that information to the public. Regarding the 8 percent of cocaine that tested positive for fentanyl in April, I asked her what the numbers showed for the preceding months. She said they hovered within “2 to 4 percentage points,” but she wouldn’t go much farther beyond that estimate. The April number was “higher than previous months,” and “a bit of a jump,” she said. But “to the extent that this represents a spike or a continuation of trends, that’s something we’ll know in hindsight.” The NYPD, which investigates all drug overdoses after they are reported, declined to comment.

“I don’t think that we can say for sure what’s happening right now,” says Dr. Tarlise Townsend, a postdoctoral fellow and researcher with the Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy at NYU Langone Health. If more people are indeed dying in the city from accidental fentanyl overdoses involving only cocaine, it is likely the result of cross-contamination—rather than intentional “cutting” of fentanyl into the cocaine supply. The amount of fentanyl in any given city’s cocaine, since fentanyl came on the scene, has very likely never been absolutely zero. Fentanyl often shows up in cocaine because suppliers or dealers who are sorting and selling it are also selling products containing fentanyl, and even tiny amounts can taint the supply. (Street drugs should probably come with a warning about other substances, the same way food gets labeled “Made in a facility that processes nuts.”)

Cocaine users who aren’t used to opioids can be susceptible to an extremely small amount of fentanyl, and they often aren’t as familiar with recovery methods like Narcan to combat an overdose. The pandemic could have exacerbated cross-contamination in numerous ways: It very likely destabilized supply chains, shaking up dealers and their sources; we know it changed habits, with people using drugs more often to combat depression or alienation, and using them alone, and it likely even changed people’s bodies. If someone stopped using for a certain amount of time when the city was shut down, their tolerance could have decreased significantly. Researchers, including some at the Health Department, say they will be studying these trends for years before they fully understand them.

For years, decriminalization advocates have been raising the alarm on the profound knowledge gap on drug use in New York City. They are the ones working with users in the hardest-hit neighborhoods, primarily East Harlem and the South Bronx (which, in 2017, had the second-highest overdose rate in the United States). Here, fentanyl is not the cause of a sudden panic that trends on Twitter. It’s a raging epidemic. Harm-reduction proponents say efforts like Overdose Prevention Centers, where people can safely do drugs in the presence of trained staff, and drug-checking materials and equipment would go a long way toward collecting better data and saving lives. But they don’t have the resources or the legislative backing. “We’ve come to expect or accept that certain communities are going to continue to die of overdose deaths,” says Sheila P. Vakharia of the Drug Policy Alliance. Cocaine-involved overdose deaths in New York overall have seen a huge spike since 2014, more than doubling by 2018, when they accounted for over half of accidental overdoses in the city. A third of those occurred in the Bronx. But people who might have died of an overdose involving cocaine and something else, like heroin, or those who even sought out fentanyl, don’t make headlines the way that people who supposedly died after taking only cocaine (which happened to be laced with fentanyl) in a club do. “The profile of the user matters,” Dr. Vakharia says, along lines of race, class, and geography. When it’s young people in a gentrified neighborhood, “there’s an element of shock value,” which is demonstrated by the fact that I was assigned this story, for this magazine, at this moment.

There is almost certainly not one or even more than one “bad batch” of cocaine going around Brooklyn right now, for which we should all carry Narcan for a time until it’s safe. Two worse things are probably true instead. The first is that, on the whole, no one really knows exactly who is dying in this city or from what. The other is that the incursion of fentanyl and all other kinds of historically powerful synthetics into the illicit drug supply may have reached a tipping point, at which no drug bought off the street is truly safe for consumption. In 2019, NYPD laboratory testing found more fentanyl in both heroin and cocaine — and ketamine, meth, and benzos. Fentanyl was found in 75 percent of overdoses. An oncoming wave of deaths among drug users is a lot harder to acknowledge than the short-term, siloed panic that “there is fentanyl in the cocaine.”

Because that sentiment was shared with such speed and specificity among members of the media class, it has already become a dark, callous joke online. The rush to carry Narcan, or at least to say you’re carrying it, is the new virtue-signaling. Accordingly, many users report that — despite all the tweets, infographics, and demos at DJ sets — little has changed in the way of behavior. With the pandemic barely over, there is a creeping feeling of “here we go again,” a woefully inadequate public-health response to an epidemic will get filled in, however misinformed and desperate, by us, the people whose friends die, the friends of their friends, the people who post about it, the people who take no heed.

“At a party a couple weeks ago,” a friend said, “I watched some people who are very cautious about coke right now just throw their hands into a baggy of Molly and rub it all over their gums. I was like, What!?”

“I mean,” they added, “I did it too.”

This story has been updated with changes to a statement previously attributed to Dr. Tarlise Townsend.