When I was a little girl, I had a lot of Miss Piggy stuff. I remember most vividly a white sweater with her in a hot-air balloon shaped like a heart. I used to walk around the house, doing little karate chops, backhanding imaginary people, and yelling out “hiiiYAAAH!”—like Miss Piggy whenever she saved the day or needed to get rid of someone who was working her nerves. After I graduated from college, I took a karate class for the summer and my mother remarked, “Well, you finally get to be Miss Piggy, don’t you?”

I connected with that felt porcine femme. She was stubborn, bossy, and passionate. She loved Kermit, and Kermit loved her back. His frowns and exasperated sighs went along with all the other images of put-upon men in relationships, like Mr. Furley from Three’s Company or Archie Bunker on All in the Family. The world kept telling me that men, even as frogs, hated relationships, especially with women, and they tolerated both because they had no choice. The way to a man’s heart was to wear it down.

Kermit didn’t even have anyone else he was interested in. He had too much on his plate as the logical Muppet, the leader, the one who tried to keep all the other creatures from getting into shenanigans. Honestly, it doesn’t even matter why he didn’t want to be with Miss Piggy. She refused to take no for an answer, vacillating between high-pitched baby talk and snuggles to woo him and backhanding him through walls when he refused her. As a child, I laughed along. Miss Piggy’s mood swings and violence were supposed to be funny. If nothing else, they were familiar.

My father drank and did drugs. He couldn’t (or wouldn’t) hold a job, resentful that someone as intelligent as he, even without a college degree, would have to do manual labor to make a living. My mother was the breadwinner. After my mom had my brother, J, the last of her three children, she tried to be a stay-at-home mother, hoping that would force my father to get a job and provide for the family. It didn’t work. We remained in the projects, living on government assistance, until my mother went back to her old job as a dialysis nurse. Around the time my brother turned two, he was diagnosed on the autism spectrum. Mama knew she needed help to make sure my brother had the resources he would need; meanwhile, my father blamed her for making his son “retarded,” for ruining the legacy of his name.

My father would beat my mother. I don’t know when he started. It was long before my brother and I came along. My sister, Izzie, has a different father, and mine, in his drunken rages, would express all manner of jealousies about Mama’s previous relationships. If my sister tried to stop him, he’d sneer, “What’re you gonna do? You gonna call H? You think he can save you?” He never beat me or my sister, but he would be so mean with the belt to my brother when he misbehaved. I don’t know if he thought whooping J would make him “normal,” but it was terrible to see.

My mother’s hard work plus the help of a relative on my father’s side pulled us out of the projects and into a three-bedroom house in North Nashville, a working-class neighborhood. My father’s violence and addiction came along. One night, I watched him punch my mother so hard she flew backward across the room. Her fall broke the coffee table. I’d stubbed my pinky toe on that table once, leaping from chair to couch, and my toenail had fallen off. I hated that table, mad that it had ruined my flight. I used to wish I were magic so I could make it disappear. Watching my mother land on top of it, seeing it break beneath her weight, my father hovering over her, his face red and sweating, I was mad all over again. Why couldn’t I have made it disappear or even better, made a portal appear, a gateway to safety for all of us?

My father went to jail that night. When he got out and came back home, he pulled me into his lap and explained how much he loved my mother, even though sometimes she made him angry. So you see, I was used to seeing someone use love to send the object of their affection through walls.

I would eventually realize how abusive the relationship between Kermit and Miss Piggy was. In 2011, I went to see Jason Segel’s revival movie The Muppets and almost cried at how peaceful it felt seeing the pair appear on-screen. The Muppet characters made me remember what it was like when all I had to worry about was how many bowls of Toasted Oats (the Kroger store brand of Cheerios) I could eat. Then Miss Piggy began exhibiting her jealousies. As an adult woman, I saw her issues magnified. She craves attention and flirts wildly, but if Kermit even talks to a female Muppet, Miss Piggy flies off the handle. Kermit is sensitive and thoughtful but walks on eggshells. He is afraid of her. He gives in to her demands to avoid her anger and violence.

I think of Kermit when I find myself spiraling, wondering why an ex refuses to love me the way I love him. When I find myself thinking, I can make him love me, I see Kermit’s lips folded in frustration, his cute little Muppet face shaking as he tries to keep Miss Piggy’s anger from rising. It may be a little silly to think of a child’s puppet in the middle of a lovelorn breakdown, but it’s my way of remembering that forcing myself on someone is violence in and of itself. I’ve had enough of that.

I haven’t always calmed myself down. I’ve been stupid and petty, leaving high-pitched voicemails, hoping to coerce a response. No felt or cotton here, but I’ve offered the softness of my body to avoid rejection. I have relished the glint of fear in an ex’s eyes as he glances around, wondering if I will cause a scene if he doesn’t come home with me. I am not perfect. Unlearning this kind of manipulation is a process, but thank God for the magic of maturity and self-awareness, portals of safekeeping that finally did appear.

Miss Piggy still speaks to me—a passionate woman who knows her talents should be recognized—but Kermit is the totem I use when a broken heart tries to tell me I am my father’s child.

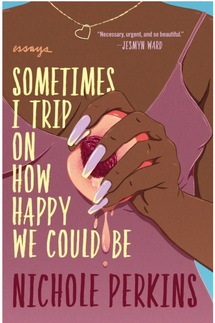

Excerpted from the book Sometimes I Trip on How Happy We Could Be by Nichole Perkins. Copyright © 2021 by Nichole Perkins. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Every product is independently selected by our editors. Things you buy through our links may earn us a commission.