Everyone always talks about how blue the skies were that day. As if the weather were a decoy.

I don’t remember the sky. The only memory I have is borrowed from my mom’s retelling, just a single moment from that morning. The two of us had been on our way out the door for my 9 a.m. swim lesson when she caught a glimpse of the TV and froze. I tried tugging on her arm, but a grainy image of dark, thick smoke pouring into the cloudless sky had her full attention. My pop-pop turned up the volume to hear news anchors reporting the tragedy. Later that night, my aunt took my sister and me to get ice cream and ran into a teacher from my school. I don’t remember that encounter, either, but as ice cream dripped down our hands, my aunt later said, she stepped away to whisper to her, “Their dad is one of the missing.”

In the days that followed, I spent time playing make-believe in my basement with cousins whose parents told them to be especially nice to me. Above us, a new world was unfolding, one filled with phone calls to hospitals and photocopying missing-person posters plastered with a cropped close-up of my dad smiling in a polo shirt. In the original photo, my mother stood behind him on her tiptoes with her hands on his shoulders, both of them showing sincere smiles, likely listening to the giggles of my sister and me in the background. We could never have imagined that this photo would be the one the world would remember my dad by for decades to come.

By the end of that September, the posters were mostly taken down, and our hope that my dad was missing had given way to the cruel reality that he was gone. One thing I do remember from this time is my sister and me in our New Jersey backyard at dusk, each of us holding on to a balloon by a string as lightning bugs grazed our ankles. “Count down from ten, then let go and look up,” my mother told us, and we did, following the balloons as far as we could see. “That’s where Daddy’s sleeping in Heaven tonight,” she said.

Since then, I have spent more time than I’m willing to admit trying to figure out who my dad was and how our worlds intertwined despite existing in different dimensions. And while I know what to say when someone new asks about my family, I always dread the questions — the way people’s faces fall when I share that my dad passed away on 9/11, how they recoil with a mix of sadness and discomfort when I repeat the well-rehearsed lines: “He worked on the 99th floor of the South Tower. I was 5 years old when it happened, just a few days after I started kindergarten.”

Sometimes they’ll exclaim at how young I was and assume I don’t remember him, almost as if my youth had let me bypass the trauma and suffering. I hate to admit it, but in some ways they’re right. The truth is I remember the aftermath of the event more than I do the time before it. The days when our house filled up with toys and teddy bears and our evenings were occupied with bereavement groups and art-therapy classes. The hours spent sitting in front of a therapist who asked probing questions about my feelings as we played Chutes and Ladders. The well-intentioned attempts to help me trudge through the seasons of suffering, to move forward, to move on.

In my father’s absence, we remembered him in the ways we could, through his love of music and his collection of classic-rock records and cassettes. In the car, my mom let my sister and me sing along to the lyrics of Pink Floyd, belting, “We don’t need no education,” knowing it would have made him laugh. I vaguely recall my mother buying him an electric guitar for his 40th birthday, a sleek red-and-white Gibson, though she says he only ever knew how to play air guitar, and his passionately strumming along to solos as he listened to records by Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers and Roger Waters. I imagine this gift symbolized both the passing of time and the youthfulness still within him, the chance to learn a new skill, to become some amateur version of the rock stars he idolized. I’m sure he picked it up a few times, anticipating that he would learn how to play it once life calmed down a bit. After all, he assumed he had nothing but time.

It’s strange to lose a parent in a tragic event that is so publicly known but so privately grieved. On September 11, 2002, the one-year anniversary, my godmother drove up from Virginia and helped my sister and me bake a cake with a Barbie doll stuck in the middle. We decorated her cakey skirt in patriotic red, white, and blue sprinkles and icing. Other days, we would visit local memorials as they cropped up, snapping photos of my dad’s name carved in stone and dropping off trinkets as a way to remember.

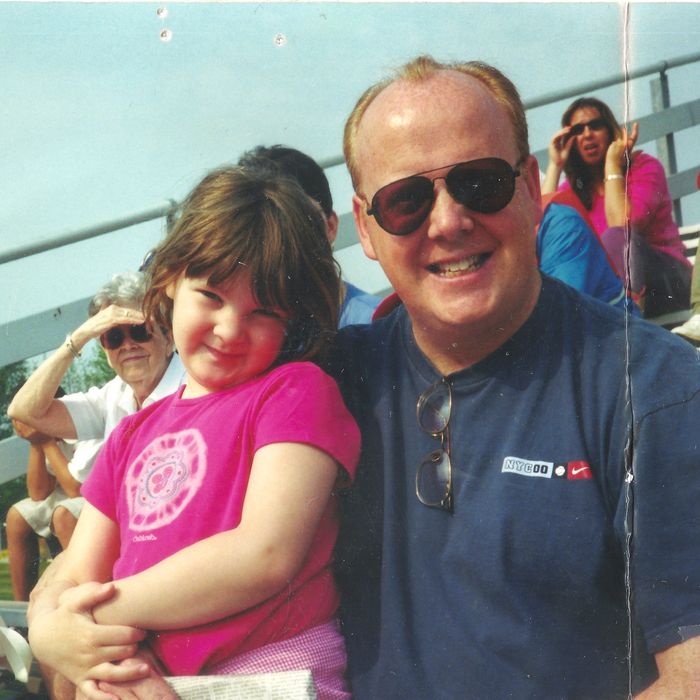

Sometime after the cleanup at ground zero, a bell tower made with steel from the World Trade Center was erected in Sterling, New Jersey, near our home. Beneath it we buried a Foster’s beer tap. Anticipating one of our visits, I decorated a small wooden box with glitter and gemstones and placed my favorite photo of us on the very top — a toddler version of myself winking as I “cheesed” with my dad, his wide blue eyes twinkling. Inside it, I wrote a note just for him. But over time, these outings didn’t bring my dad to mind, only the way he was taken from us.

I spent hours of my childhood rummaging through boxes of photographs and home videos that were never enough to revive my memories of him. Later, I would Google his name and read legacy pages filled with heartbroken messages from his co-workers and friends, sifting through the digital debris in search of the remains of a life I didn’t get to know.

As I grew older, the lines between who he was and how he died continued to blur. In a corner of my childhood home, there was a tall glass curio cabinet — our very own memorial. On one shelf was a drawing of an airplane approaching the towers that I had made soon after the attacks. In the sky was an image of God with open angel wings next to a quote bubble that said, in my shaky 5-year-old’s handwriting, “Noel, it’s your time.” Thinking back, I don’t know who chose these words. Now, at 25, I find they still don’t compute.

On the lower shelves of our memorial cabinet were a few model cars he had collected, including a miniature version of the red Camaro he drove to work that day. I have held tight to the fuzzy memory of the real-life model and how he managed to squeeze a two-in-one TV and VCR player in the back seat so my sister and I could watch Barney & Friends on our trips along the Garden State Parkway to visit family down the shore.

I now live in that same little beach town on the Jersey Shore, surrounded by my Mom’s many relatives from our extended Irish Catholic family. There’s no memorial for him here, but whenever my dad’s name comes up among family members, they invariably recount the last time they saw him. It was Labor Day weekend 2001, and my aunts, uncles, and a dozen or so cousins all brought their kids to see the fireworks, parking their beach chairs side by side in the sand. While the other kids delighted at the sparkling sky, I was terrified of the pyrotechnics, eventually finding my way into my father’s arms, hiding my head beneath a beach towel until I heard the audience’s applause. I think this is my last memory of him, too, holding me tight and reassuring me I would be okay.

In spite of everything, I still believe my father is protecting me somehow. Ten years ago, when I was diagnosed with leukemia just before my 15th birthday, a string of synchronicities followed. I was cared for by a nurse whose husband had worked with my dad and by another nurse who lost her brother, a firefighter, that day. Around the same time, I learned that my dad had frequently visited a friend’s sister who had leukemia in a New York City hospital decades earlier. As I worried about my fate, these signs comforted me. It seemed that, unlike my dad, I was in the right place at the right time.

But in some ways, being a 9/11 kid has felt like a standard to live up to or a label I must wear, marking me as a kind of poster child for 21st-century grit. I’ve always felt this pressure. After surviving cancer, I went on to complete college and a master’s degree, started a career as a wellness coach, and will soon co-author a book. With each accomplishment, I am reminded that my dad would be proud of me, his baby girl who now resembles him with our oval faces, rosy cheeks, and above-average height. But I also wonder who I would have been if I hadn’t had to be as resilient.

I’m still learning to embrace the few pieces of him I’ve claimed that exist outside the tragedy that took his life. I haven’t entirely let go of my bitterness, but it’s clear to me now that he wouldn’t want his existence to be defined by a single day in September. And I won’t let mine be defined by it, either.