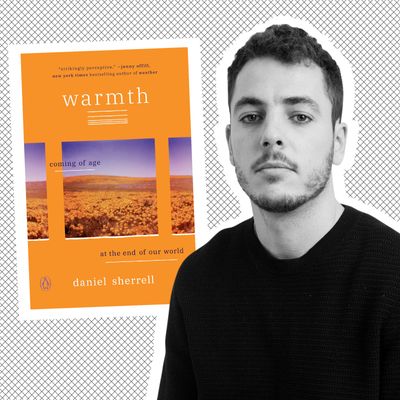

How do you live in a world that is ending? This is the central question of Daniel Sherrell’s debut book Warmth: Coming of Age at the End of Our World. Half-memoir and half-love letter to a future child, Sherrell’s book provides insight on how to navigate a world threatened by climate change — from the overwhelming anxiety it conjures to the existential quandary it wreaks.

When faced with the collapse of society, it feels increasingly pointless to accomplish all the things we are meant to do in life, including planning for a future and taking care of our mental health. Discussing, processing, and responding to these emotions often feels as insurmountable as halting carbon emissions itself.

Sherrell, an activist who helped lead the passing of green bills like the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, struggled with these same ontological plights. In a narrative that spans Sherrell’s up to his 30s, Warmth captures moments in his life as he fought to overcome global warming (which he dubs “The Problem”) and his own questions about building a future and family. The Cut spoke with him about dealing with climate anxiety, remaining hopeful, and the benefits of writing to fictitious people.

How do you navigate the anxiety and grief related to climate change?

Every now and then — literally once every few months — there would be a morning when I would wake up and feel the full weight of the climate crisis settle on my chest, and I wouldn’t get out of bed. It was a feeling similar to depression. And, as I say in the book, as hard as those moments were, they felt kind of precious because it was the only time I was living in reality. Of course, that was difficult. But also, it felt cathartic, like I wasn’t sleepwalking. So I started writing. I wanted to write into those moments and unfold them and see what they contained. My intuition was that if I never unpacked that Pandora’s Box, I was going to be truly fucked up in the decades ahead and wouldn’t be able to keep doing the climate organizing work that I intend to be my life’s work.

I think climate change feels overwhelming for a lot of people. The thing that I tried to do in this book was to make it so people don’t turn away from these feelings, but to hold them as real, valuable, and worthy of examination, like other strong emotions in life. This book is trying to do justice to that set of emotions by sitting with them and not shutting them into some avenue of easy despair or optimism.

In the chapter “Loss,” you describe the onslaught of bad news you receive about climate change, from politicians undermining green bills to Hurricane Sandy. Where do you find the hope to keep pushing on despite worsening conditions?

When the latest IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] report was released, a lot of people who don’t engage with the climate crisis woke up to it and became doom-and-gloom bros on Twitter. My feeling was the opposite. What the IPCC report made clear to me was that there’s still a huge swath of outcomes that can happen between 1.5 degrees Celsius, where there are still hurricanes and flooding but we’re able to take care of most of society, and four or five degrees Celsius, where we can’t feed or hydrate huge portions of the population. And for every hundredth of a degree that that thermometer moves between those two poles, we save or consign millions of people to life or death.

For me, there are still extreme moral stakes here. How am I going to give that up? How can I give that up when people — who are much more exposed to the problem than I — haven’t given up. We’re in this together, and there’s still a lot of uncertainty. In that uncertainty is where I locate hope, which is basically the will to keep holding hands with the people you love and step forward into the future rather than cower from it or put blinders on.

You wrote this book as a self-described “young person” — basically, at a time in your life when finding purpose was at the forefront of your mind. How did you manage to do this while contemplating the end of our world?

It is a terrifying and sad time to be alive, but I don’t think it’s without meaning. If I was living in what the ’90s purported themselves to be, which was an undying shopping-mall culture where we all consume and die, that would feel meaningless. Living in this time, where the fate of the entire human world is at stake and there’s actual physical work we can do to change that fate … I can’t think of a more meaningful thing. I found meaning by getting involved in the climate movement — one of the most beautiful and consequential social movements in the history of our country, maybe the world. Greta Thurnberg has that adage, which is a little cheesy and also totally true: “Hope doesn’t produce action, action produces hope.” Joining forces with people who share my values to not only salvage the world, but also create the world we want, that’s been the most meaningful component in my life.

Can you talk about how “The Problem” impacted your sense of time and how you choose to spend it?

It has really fucked up my sense of time. Growing up in the ’90s, you could live in biographical time. It was the end of history, Francis Fukuyama had declared. So history would keep plodding along, and you could just live your life and forget entirely about geological time. The climate crisis jumbles all those categories together. The dynamism of the Earth seems to be now outpacing the dynamism of human life. Now, it feels like everything’s constant. We have our foot on the pedal, and the pedal is on the floor. I hate that feeling of being dragged into the future against my will, meanwhile the passage of time brings you deeper and deeper into ecological catastrophe.

On the other hand, this has made me cling even harder to the present, to still find joy and meaning in small observations and little pockets of time that don’t feel measurable. I’ve gotten much more serious about mediation, taking a walk every day and leaving my phone at home. Also, the climate crisis forces us to think way out past the bounds of our lifetime to take into ethical and political consideration people who are not born yet, and how the choices we make now have material impact on the lives of seven, eight generations from now. The human lifespan has created a myopia of self interest around itself — its circumscribed the boundaries of our attention — and the climate crisis explodes that and good riddance, frankly.

What advice would you give to others who are struggling with coming of age during these times?

I felt many times, this sense of What’s the use? Why am I going to work every day if the world’s going up in flames? Honestly, I think it’s a valid question. As climate change gets deeper, many of the institutions that we’ve gotten used to as structures in our lives are going to seem more and more arbitrary, strange, and out of date when juxtaposed against increasing wildfires and superstorms. If people are asking, “Why am I going to work?” that’s a productive question to be asking yourself. Don’t do it alone. Do it in community, and find your way to the climate movement. There are many ways to join it — you can join your local sunrise hub or get involved in Justice Democrat campaigns. I know when I tell people this they think, That’s another chore on top of everything I’m trying to do to make my life work. But this is the single best antidote to crushing climate overwhelm. Getting together with other people who are struggling with the same questions can be immensely healing.