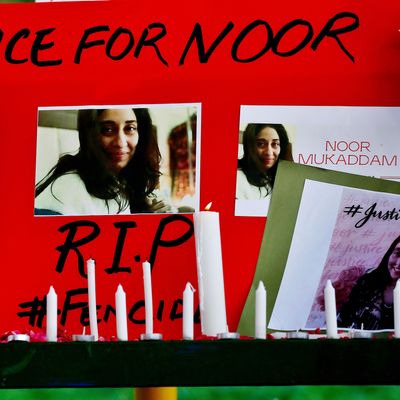

Noor Mukadam was a charismatic and graceful woman, her father Shaukat Mukadam told the crowd. The late-September vigil was being held for his 27-year-old daughter who was allegedly beheaded by Zahir Jaffer, an acquaintance of hers and scion of one of Pakistan’s richest families. “My daughter is gone,” Mukadam, a former diplomat and ambassador, told the group gathered before him, “but I want that all the daughters of Pakistan should remain safe.” As he broke into tears, his one demand for the upcoming trial, which was set to begin this week, was that there be justice for Noor.

Noor’s murder took place among an especially horrific spate of crimes against women in Pakistan. It has captured the country’s attention not only because it’s especially gruesome but also because Pakistani women are utterly fed up with rich and powerful men committing crimes against them and getting away with it. Noor’s case has become a rallying point against the hypocrisy of a society where women are present in all sectors of the economy and public life but where there are few places for them to turn to when they face abuse at the hands of men. As Pakistan watches, feminists are wondering: Could this time finally be different?

The murder took place just over two months ago, on July 20. At around dusk, Zahir Jaffer, who had held Noor captive for the past two days, allegedly raped, tortured, and killed her. In the days following the crime, Zahir Jaffer’s parents, who phone records show were in contact with their son and household staff before and after the murder, were also arrested and placed in police custody, as were the household’s guards, cook, and gardener, all of whom were present at the time of the murder at the Jaffers’ sprawling home in the most exclusive enclave in Islamabad.

According to the police investigation and CCTV footage, Noor attempted to escape, but Zahir’s armed security guard did not let her leave. Later that evening, she jumped down from a balcony. This time, it was the gardener who locked the gate and refused to let her run. Zahir Jaffer emerged from the house and dragged her back inside by her hair. She was never seen alive again.

Zahir Jaffer’s multimillionaire parents then tried to orchestrate a cover-up, according to Islamabad police, calling a therapy center where Zahir had once been in treatment and asking them to send a team to their house, allegedly to dispose of Noor’s body. Had a neighbor not called the police, they may have been successful in doing so. Later that day, Shaukat Mukadam was asked to come to their home, where he identified the body and the severed head as Noor’s.

It would appear to be an open-and-shut case, but things are not simple in Pakistan. At the outset, there are laws that favor the powerful. These include ordinances that essentially permit any accused to be “pardoned” by the victim’s family. When the perpetrator is rich and the dead woman is poor, her family faces a lot of pressure to capitulate and grant the pardon. There are also unofficial ways to interfere: Police and even judges of the lower courts are poorly paid and often amenable to bribes. And since there is no jury trial in Pakistan, trial outcomes are decided by the judge alone. Powerful families can buy off witnesses or even pay armed thugs to intimidate or blackmail those refusing to do the bidding of the powerful. Pakistan’s confusing mess of parallel court systems also presents its own morass.

And despite the inordinate amount of violence Pakistani women face, they do not often see their perpetrators punished. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan recorded 363 honor killings of female victims in 2020, and according to a recent study from Pakistan’s Ministry of Human Rights, about 28 percent of women and girls between the ages of 15 and 49 have suffered violence during their lifetimes. Even when they make it in front of a judge, less than 3 percent of sexual-assault cases result in a conviction. A new bill that would criminalize domestic violence has spent months stalled in Parliament after some members from Islamist parties opposed it.

One reason Noor’s case has been able to evade the usual traps is because of the intense pressure from social media, where the hashtag #JusticeForNoor trends every time there are new developments. And while her case has certainly received more attention because of her upper-class background, it also aligns with growing anti-elitist sentiment in Pakistan; people who are not part of the multimillionaire elite have had it with the impunity with which men (and sometimes women as well) heap abuses on the less powerful. At his first press conference, Shaukat Mukadam alluded to the ruling Pakistan Justice Party, which vowed to hold the country’s corrupt elite class accountable: “The government belongs to the ‘justice’ party, and it should ensure that this justice is actually done.”

Feminists and anti-elitists are now speaking up in any way they can. YouTubers like Mahreen Sibtain and Maria Ali have been providing daily updates on the case, dedicating video segments to everything from how Zahir isn’t allowed to have a toothbrush in his cell to how his mother is spending her time in jail. Ali never once uses Zahir’s actual name, referring to him as “the beast” instead. Her anti-elitism is popular, particularly with middle-class women used to working hard for even the smallest privileges. It may not seem like a nascent feminist revolution, but this push for gender justice is supported by rapid urbanization and a critical mass of women entering the workforce. Increasingly unwilling to accept a dependent status, they are becoming more outspoken in their criticism of men.

But Noor’s killing has yet to be avenged. The trial was scheduled to begin on Wednesday, with the indictment of 12 people in connection with the murder. But before that could happen, lawyers representing Zahir’s parents introduced motions claiming they never received evidence from the prosecution, including the CCTV footage. Another motion alleged that Zahir has been unable to communicate with his lawyer. The start of the trial was delayed to October 14. This is not a good sign, but bringing the wealthy and powerful to task has never been easy anywhere. When it does begin, Pakistan’s women will be watching and waiting to see if the system will work, if there will be justice for Noor Mukadam and thus hope for them.