On this week’s episode of The Cut, co-host B.A. Parker tries to pinpoint the line between stanning and creeping when it comes to celebrity and fandom. She spoke with Cut Instagram editor Taylor Roberts about the infamous couch guy, and with senior writer Katie Heaney, who first wrote about parasocial relationships in 2017. Parker also sat down with podcast host Sam Sanders and OG YouTuber Connor Franta to discuss what it’s like to be on the receiving end of these one-sided relationships.

The Cut

Subscribe on:

To hear more about unsettling fan mail Sam received and what influencers think about us being their fans, listen below, and subscribe for free on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen. You can also read the full transcript below.

TAYLOR ROBERTS: I think you have to reach a very specific height. There has to be a bar for entry, because I don’t have many followers on anything. I have like a K here and there.

B.A. PARKER: You have 34.6K followers on Instagram, 20.6K followers on TikTok, with 3.8 million likes.

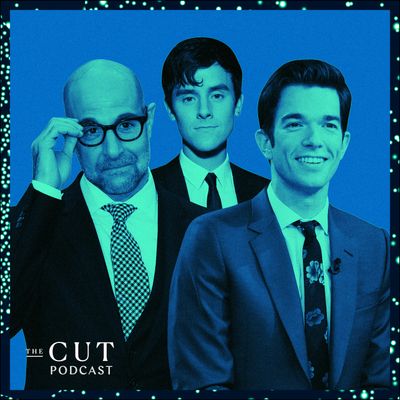

TAYLOR: Okay, that’s true. One of our best-performing posts was a picture of everyone’s favorite, Stanley Tucci, eating pasta. Incredibly hot. I think the caption is like, “POV: You’re in Italy and this man sits next to you eating pasta. What do you say to him?” That got a lot of comments and a lot of likes and a lot of shares because everyone loves Stanley Tucci, but everyone loves and no one actually knows him. We might like to think that we do, but you want to tap into this cultural “everyone wants to fuck Stanley Tucci moment,” or at least eat pasta with him, you tap into that for likes and engagement. At the end of the day, I’m like, What am I actually asking people right now?

The couch guy is insane. This young woman went to a college to visit her long-distance boyfriend and set it to music, I think it’s to an Ellie Goulding song, and I hope Ellie Goulding’s making a fat check from this.

PARKER: What happens in the video is this young woman walks into a room of other college students.

TAYLOR: She got a little like a rolly backpack. And on the couch, “hence the couch guy,” the proverbial couch guy, is her boyfriend. And three other young women. I think what most people picked up on was that the reaction wasn’t necessarily bells and whistles, ticker tape parade, screaming, running, hugging, kissing. He sort of just stood up and gave her a not-so-romantic embrace. I think the general consensus is that the vibes were off.

PARKER: It’s a fairly innocuous video on TikTok that currently has over 63 million views and over 100,000 comments that are mostly some variation of, “Hey bestie, your boyfriend’s most definitely cheating on you.” There have been re-creations, commentary, frame-by-frame analyses. Even Taylor herself went viral with her commentary on Couch Guy.

TAYLOR: The people who were commenting were upset when she disagreed with them. It was a relationship with two people, that’s not a relationship with millions of people. They go in with things like, “He’s gaslighting you, and now you’re gaslighting all of us” and it’s like, we’re not in a relationship with those people at all.

PARKER: The Couch Guy himself commented on this in his very last word on the matter. He said, quote: “You’re welcome for getting you off berries and cream TikTok, but remember: Not everything is true crime. Don’t be a parasocial creep. Go get some fresh air. Take care.”

-

KATIE HEANEY: I think that the way that I see fans defending or standing by an artist that maybe is getting criticism for doing something, oftentimes, that they deserve criticism for, yet the fans swarm and are like, “No, we’ve got her side. We know her, we know what she’s going through. You don’t know her like I do.” It’s like, Well, neither of you knows her at all. This is just in your head. It’s probably only intensified since I wrote about it first.

There are a lot of different ways that people form relationships with social-media personalities. People are maybe arriving at personalities in a less direct route. Now you could sort of stumble across a fight happening on Twitter or something, like the bad art friend from the other week, and get all of a sudden invested in that when you maybe wouldn’t have come across that material organically. One of the people that I was writing about as sort of a hate-follow, I’ve converted into a genuine fan. I don’t know what that says about the power of parasocial relationships.

PARKER: Wait, what was the shift?

KATIE: Maybe Stockholm syndrome. Even if you think you’re doing something ironically and you think you’re making fun of someone, if you are with them long enough, maybe they could just grow on you.

PARKER: And that shift can be surprising. But as weird as it is finding yourself suddenly texting friends about some college kids on a couch or the possible hidden meanings behind John Mulaney’s ex-wife showing her TikTok followers how to put on a duvet cover … it’s even more unsettling being on the receiving end. Now, Sam hosts the weekly radio show It’s Been a Minute With Sam Sanders, and he’s used to getting tons of emailed feedback — good and bad. But one stood out so much that he had to post parts of it on Twitter.

SAM SANDERS: I read every letter. I read every one. This is a letter that I got on August 19, 2021, at 3:06 p.m.

“Dear Sam, I’m writing to tell you that I will be taking a break from your podcast and all podcasts in general. I’m a little sad about this because I have been listening to you for years and you have been my favorite for a long time. Just have to take a break because it’s just not a treat for me anymore. Take your latest show, for example. I don’t think you would have done the discussion about soap if you were still living in Texas. I think it was just served to you by some lazy L.A. producer. I know you. Even though you consider yourself a private person, you have revealed yourself a lot over the years.”

Isn’t that creepy?

PARKER: Yeah.

SAM: “P.S. I live in Camarillo, or Camar-EE-llo. So if you ever want to eat a burrito with me, come on down. Smiley face.”

PARKER: When you read that for the first time, what were you thinking?

SAM: I think what I was surprised by were the parts where she’s just like, “I know you.” That felt creepy. Also, “Come and eat a burrito with me.” Like, oh no, no, no, I eat burritos solitarily.

She could do a better job of understanding boundaries, but I also think that during this pandemic year, we all have drawn close to voices and people and things that we don’t actually know. If there was any time for parasocial relationships to flourish and perhaps grow in some unhealthy ways, of course it had to be this past year and a half of pandemic when we all were dealing with extreme isolation. I need to offer some grace to this woman writing me out of pocket. It was a really weird, shitty, strange year.

PARKER: I didn’t realize that the person was a woman.

SAM: That’s so weird. When I shared it, everyone thought it was a guy. It was a woman.

PARKER: Do you think part of the way that parasocial relationships are being viewed right now is because women and girls are often the ones ascribing to having that relationship towards celebrities, so it’s now considered kind of icky or something to judge?

SAM: Yeah. We think less of it or think it’s weird because women like it. We can never embrace it because we think that a thing that women like could never be worthwhile and worth discussion.

PARKER: So much of my childhood was spent memorizing facts about Leonardo DiCaprio that if I had known like 15 years later, (a) I’d be considered too old for him to want to date me, and (b) it would be considered something to look down upon, but it’s just part of the job of being a fan, I wouldn’t have invested so much time.

SAM: This is my whole theory about hard news versus soft news. I think that hard news is just what prototypical straight white guys think is interesting and soft news is what everyone else thinks is interesting. And soft news is more likely to have stuff that speaks to people of color and women and queer people. We subjectively think that the most important stuff is the things that Chad thinks are important.

KATIE: It can help people feel less lonely in some ways. If people have a role model or someone that they genuinely like, and they keep up with that person’s life, and maybe that person likes some of their comments once in a while or something, that can feel good. Who doesn’t want to feel like they’re getting attention? But it’s so easy to go overboard.

If you want to follow a relationship online, try and put clues together yourself. Maybe have a group text about it, piece things together. That’s one thing. But if you are going to that person that you don’t know and demanding answers, I think that’s where the line is for me. I’m mystified when I see someone comment on a post about a breakup and be like, “Well, what happened?” Do you think that this person is going to respond to you directly? Where does that entitlement come from? There is some role that the influencer, or whoever it is, plays in creating that idea because they are making you think that you have a window into their life and that you’re really a part of it.

PARKER: A parasocial relationship is by definition one-sided. But what about when an influencer is creating the illusion of a friendship? When does that relationship stop being an illusion, and what happens when even real friendships start to feel parasocial?

CONNOR FRANTA: It’s kind of the age-old question for social-media personalities. Are they acting, are they a fake version of themselves, a heightened version of themselves? You’re like, I don’t know at what point it is me and it isn’t me.

PARKER: So you have close to like 8 million followers on Twitter. You have like 4 million followers on Instagram. You have 5 million followers on YouTube. Why? Why would you want that?

CONNOR: I began to question the same thing the older I get and the more I get into it. This was a choice, wasn’t it? It was a permanent choice that I didn’t realize would be permanent at the time.

PARKER: What number felt like enough and what number felt like too much?

CONNOR: I remember hitting milestones, like 1,000 subscribers. I’m like, “Who are these thousand people?” That’s an unfathomable amount of people. I grew up in a town of 4,500 people. I started my YouTube channel in Minnesota where I grew up — it has like 5, 6 million people in the entire state. So sometimes, perspectives like that throw me for a loop where I’m like, Wow, I have almost double the population of Minnesota on Twitter? Ugh.

I was one of the first on YouTube, which is a really weird thing to say. It doesn’t feel real. I was trying to explain to a couple of younger people on TikTok I was talking to the other day at an interview, saying, “It’s hard to imagine, but imagine uploading a video titled ‘How to wear pants ten ways.’ That would be the only video on YouTube titled that. And that was when you could be uploading anything to YouTube. That’s how long I’ve been on the platform.”

I think my channel got a lot of attention because I was one of the first people to come out after already having a large platform. The video got 10 million views overnight. It had a million comments and a million likes. It had so much interaction, it was in the top-five trending topics on Twitter. I remember just feeling so small in something so big because I didn’t expect it to be that big of news.

PARKER: How do you process being a trending topic on Twitter?

CONNOR: With grace. It was terrifying. You do things without having fully processed them yourself. I had come to terms with being gay. I didn’t know what it meant to be gay. And yet, I told the whole world I was that. And then I was being bombarded with questions about it that I didn’t have answers to and attention around the topic that I didn’t necessarily want. I wanted people to know and to stop asking me about it, but I guess I didn’t think far enough ahead in that sense.

PARKER: Twice the population of Minnesota knows your business.

CONNOR: I know.

PARKER: Did you feel pressure to maintain that level of intimacy throughout all of your videos?

CONNOR: I’ve been thinking about this a lot more in recent years, how interesting it is that the internet, and I guess just art in general, rewards you for your pain and your trauma. The more you’re willing to share, the more rewards you’re going to reap. So a video that says, “I’m happy” is going to get ten views, a video that says, “Revealing my trauma” is going to get a million views. Anything that I upload that reveals some sort of inner personal struggle does better and people feel more invested in me for it, so there’s this kind of sick cycle of knowing that, but not allowing yourself to take advantage of it, but then also being aware of it. It is strangely tempting.

PARKER: So is your book called House Fires because you low-key just want to burn it all down?

CONNOR: Kind of. [laughs] I guess I called it House Fires more so because I see all the little struggles and all the little traumas that we go through as a form of a house fire. You build up this safety net, and then you have to eventually burn it down for better or for worse.

PARKER: So much of being a vlogger feels like you’re just promoting a parasocial relationship. Do you feel that?

CONNOR: I could see how people think that way, but I know tons of vloggers who call their followers their friends or have some sort of nickname for their followers or whatever to make it seem more like a family. I fully get that. A lot of these people, they’re uploading daily vlogs, streaming daily, responding to comments, recognizing names. So who’s to say it isn’t a real relationship to a certain extent? Especially if the person who is fostering the relationship is the creator? If they have good intentions behind it and they’re not just truly some maniacal little demon profiting off of these unsuspecting souls. I guess it’s kind of a modern relationship that needs to be studied. I do feel like I have a personal connection with the people that follow my content because I’ve been doing it for so long and people have been around the whole time. I can’t help but feel close to those people.

PARKER: When I think of how many followers you have, I immediately think of it like a megachurch.

CONNOR: Ma’am!

PARKER: I’m sorry! But there’s a point to this, I promise.

CONNOR: This is a gays-only event.

PARKER: There are so many people at that church. How can you have a one-on-one connection? So when you have like 20 million followers, how do you have any kind of intimate connection with that many people?

CONNOR: Yeah. That’s an answer I don’t have. There are a lot of individuals who I know their Twitter username, I’ll know their first name, if it’s a Twitch chat, I can learn information and remember information about individuals, but clearly, I can’t remember personal information about 9 million people.

I have tons of friends in the social space, so I’ll listen to my friend’s podcast while I’m doing laundry. Then I’ll realize later on, Oh, I now know this thing about my friend that they didn’t tell me personally but that they told the world personally. Now I’m like, If this were to come up in conversation, do I tell them I already know because I heard it on their podcast? Which really shouldn’t be weird because I’m just supporting my friend. But now I feel weird that I know information about my friend that they haven’t told me.

PARKER: Do you have a parasocial relationship with your physical friends?

CONNOR: Yes, exactly. That is so unique because most people don’t have people in the social space as their friends so it’s a really weird phenomenon I’m a part of.

PARKER: There’s something I call the pentagram of “white people that TikTok loves.” It’s like John Mulaney, Bo Burnham, and Phoebe Bridgers. People are like “sweet cinnamon roll, I love you. You’re never going to hurt me.” Do you feel like because you’ve placed yourself in this world, there are instances of that happening to you? They’re like “sweet baby Connor. It’s okay. You’ll be all right.”

CONNOR: It’s my own fault because I feed into it to a certain extent without even realizing I’m feeding into it. Sometimes I’ll get mad and be like, “I’m not a baby, I’m a man. I’m an adult. Stop treating me like a cute cinnamon roll.” Then the next day I’ll be like, “I’m a cinnamon roll today.”

It is the strangest thing to have been a part of from the beginning until the present. I have the luxury of knowing what it was like in the very beginning before viral videos, like “leave Britney alone” or the shoes song. All of those things where it was before anything was even viral or whatever that meant to now. I know nothing else. I know nothing, but this weird reality that we’re in.