Humans are exceptionally cooperative creatures — most of us, anyway. On the whole, we grudgingly, but largely peacefully, pack into crowded subway cars and airplanes. We leave celebrities alone when they’re ordering a latte. We go to therapy instead of murdering our exes.

And then there are those among us who take social rules as an invitation — or imperative — to break them in large and small ways. It’s usually the little stuff: not giving up your Q train seat for a visibly pregnant person, asking for a selfie at 7 a.m., locking your ex out of your Netflix account. But occasionally, these infractions rise to the level of defrauding investors for millions of dollars, blithely skipping out on a six-figure hotel bill, or following heartbreak with murder.

Those are, apparently, our favorites.

There are at least a dozen miniseries, documentaries, and feature films about Elizabeth Holmes, Bernie Madoff, and Anna Delvey and the crimes they’ve been accused or convicted of. There’s a whole canon of material about Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker, the televangelists turned fraudsters. Tonya Harding is her own brand. Add books, podcasts, and E! specials to the mix, and there’s a practically unlimited amount of real-life villain content out there.

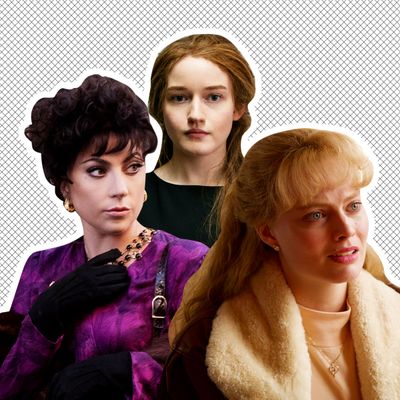

The latest entry to this canon is Patrizia Gucci, played by Lady Gaga in House of Gucci. “I don’t consider myself to be a particularly ethical person,” she says in the film. “But I am fair.” While the dominant narrative has cast her as a jilted lover who got revenge by having her ex murdered, the story is as much about money as it is about love. Patrizia (whose last name is now Reggiani) and Maurizio Gucci were literal jet-setters who socialized with Jackie Onassis and bought the world’s largest wooden yacht. When Reggiani had Gucci murdered in 1995, though, she was not the only suspect.

“Inherent in the challenge facing Prosecutor Nocerino in his arduous search for the killer is the fact that an amazing number of people had it in for the victim,” Judy Bachrach wrote in Vanity Fair reporting on Gucci’s murder, detailing the lavish life the Guccis led and the rage both Patrizia and the Gucci family, who had never much cared for Reggiani, felt when Maurizio lost the company. After the Guccis divorced, Maurizio ran the family-owned company into the ground so badly that in 1993 he sold it to a Bahrain-based company called Investcorp for $120 million. Gucci’s death, it seems, was more about being a failed rich person than a failed husband.

Still, Reggiani was too perfect a villain to overlook. Long before Bennifer and Brangelina, the Guccis gave themselves the celebrity-couple moniker “Mauizia,” which they sported on luxury-car vanity plates that ferried them from their Manhattan penthouse to their private jet to their island villa. She threw lavish “color parties” (her favorite was orange) and draped herself in diamonds and statement necklaces that reflected her most famous quote, “I would rather weep in a Rolls-Royce than be happy on a bicycle.” During her truly wild 1998 trial in Italy, when she was sentenced to 29 years in prison for paying to have Maurizio killed, Reggiani claimed that she had been blackmailed as part of the murder plot and forced to pay $365,000, but then said that it had been “worth every penny.” In 2002, she told the Italian crime show Storie Maledette, “I don’t think of myself as innocent, I think of myself as not guilty.” Today, she lives in Milan and is often seen around town with her pet macaw.

Watching these norm-breakers blow off the system, and then get caught, is a vital pressure release for our uglier emotions. They fascinate us because they allow us to explore what would happen if we stopped following the rules and, even better, reinforce why they exist in the first place. They help us sort the world into neat categories — hero and villain, good and evil. “It’s easier to hate or love a person than an abstract system of ideas,” James Jasper, a sociologist and author of Public Characters: The Politics of Reputation and Blame, explains during a video call. “So they come to symbolize all sorts of moral values.”

We’re especially drawn to characters who add a twist to the standard hero, villain, victim relationship. “We are pretty satisfied when somebody that we’re supposed to admire turns out to be not as good a person as we thought — we like the downfall narrative,” Jasper says, pointing to Elizabeth Holmes and Bernie Madoff. Villains who make victims out of people we’re secretly — or openly — happy to see punished also provide this pleasing element of narrative complexity.

There’s evidence that our willingness to punish others tends to unite the rest of us, sometimes (emphasis: sometimes) for the best. “Humans cooperate with unrelated individuals on a much larger scale and in a wider variety of ways than do any other species,” wrote the authors of a 2012 study of third-party punishment among chimpanzees. Chimpanzees will punish each other directly — you take my food, I take yours — but they will not punish a third party observed to take another’s food. Humans, on the other hand, will. “Impersonal enforcement of violations is especially critical to the maintenance of cooperation in large-scale human societies,” said the study, “in which individuals rarely, if ever, encounter each other directly.” Making an example out of rule-breakers, whether in the village square, in a salacious made-for-TV movie, or on Twitter, loudly restates the rules we’ve, supposedly at least, agreed to live by. Paying attention to whose downfall we’re enjoying can also cue us in to what matters most to us.

In a culture simultaneously hamstrung by economic inequality and consumed by wealth and status, we especially love it when someone sticks it to the rich. Jasper points to Madoff as a prime example of a hero turned villain. “It was deeply satisfying for him to fall from grace and end up in prison,” he says. “In a way, the whole 2008 financial collapse … he became a symbol of it in a way that allowed the other villains, CEOs of major corporations, to get off the hook because all the blame could be focused on Bernie.”

When we watch, say, a Netflix miniseries about a villain like Anna Delvey, we get to see inside the secret world of the very rich, confirming our suspicions that the rules are entirely different when you have a seven-figure trust fund. Her scam plays to our innate sense of justice — it’s not fair that we have to have a working credit card to cover a charmless $179-a-night room at the Holiday Inn while the wealthy glide into suites with an air kiss and the promise of a wire transfer. Likewise, Holmes exposed the absolute lack of due diligence in Silicon Valley, confirming our suspicions that those guys on Sand Hill Road writing checks to their college roommates aren’t as smart as they claim to be.

It’s not just that these villains take us inside worlds we’re usually excluded from, or that it restores our faith in the social order to see rule-breakers caught and punished. Seeing a person or group we find odious — or we envy — being taken to task can also feel just as good.

Though it may feel wrong to enjoy watching people fail, there’s evidence that it’s actually useful. “Optimal human relations are hard to imagine without our sensitivity to norms of fairness, presumably inspired in part by moral emotions linked to judgments of fairness,” wrote Richard H. Smith and Wilco W. van Dijk in a 2018 meta-analysis of the concepts of Schadenfreude, pleasure at another’s misfortune, and gluckschmerz, pain in response to another’s success, and their effect on human behavior. “Schadenfreude in reaction to another’s deserved misfortune and gluckschmerz in reaction to another’s undeserved good fortune mean that we value ‘fair play.’ Here, perhaps, schadenfreude and gluckschmerz are not empathic failures as much as suitable reactions to a sense of justice (Schadenfreude) or injustice (gluckschmerz).”

What we consider fair, though, isn’t static. Tonya Harding’s staying power in the American imagination has to do with her journey from villain to victim to anti-hero. She’s gone through several of those satisfying narrative twists we so enjoy, which have been driven by shifting notions of class and fairness. Harding’s grand narrative has evolved as we look back at the egregiously sexist setup in the media that pitted Nancy Kerrigan, consistently personified as a refined and classy lady, against Harding, the working-class scrapper: misogynist class war on ice. During the same era, the Italian press delighted in casting Reggiani as a murderously batshit ex-wife obsessed with revenge because she had been cast aside. Long a tabloid figure, she transformed from Lady Gucci to the Black Widow overnight.

Sara Gay Forden, who wrote the book House of Gucci, the source material for the movie, has said that she believes Reggiani was far more concerned for the couple’s two daughters — though largely because she didn’t want them to end up poor. “The judge summed it up really well when he issued her sentence,” Forden told Harper’s Bazaar. “He described how invested Patrizia was in the name and being part of the Gucci empire; he said that Maurizio died not for who he was, but what he had.”

In many ways, Harding is the most similar of our favorite villains to Reggiani, who grew up rich but was considered vulgar and overly outspoken (i.e., not good enough) by the Gucci family. Of course Hollywood has embraced these stories, and of course we want to know every detail. Avenging villains with changing narrative arcs validates our suspicions that good and evil aren’t actually so simple and that sometimes — often, even — the wrong people have all the power. It also suggests that justice is inevitable, even when it’s ugly. The villain’s willingness to step outside social norms when wronged or in trouble speaks to just how satisfying it is to imagine dropping the veneer of cooperation that keeps the world in order, even if for a moment.

Or, in the case of Reggiani, for a lifetime. As Bachrach reported in Vanity Fair in 1995, “Upon learning of the tragedy, his former wife summed up her emotions with unbridled specificity: ‘On a human level, I’m sorry. But from a personal vantage point, I can’t really say the same thing.’” What would that kind of honesty feel like, practiced daily? Most of us can only imagine.