On March 29, 2015, the Oxygen network aired an episode of Snapped, a true-crime series about women who commit murder. This particular episode profiled Mindy Dodd, a five-foot-tall, soft-spoken Tennessee woman who worked graveyard shifts at Walmart before she was accused of orchestrating her husband’s death.

Snapped, as the name suggests, is interested in how average women turn into killers, and Mindy’s story was a juicy one. The episode opened by explaining that from the outside, Mindy and her husband, Henry Sherman Dodd, looked like a normal blue-collar couple. They lived in a nice house in a quiet neighborhood of Smyrna with their two children. Then a shocking reveal: Before Henry was Mindy’s husband, he was her stepfather, raising her from the age of 6. When she was 18, she gave birth to a baby girl. It was Henry’s child, though no one but Henry, then 33, and Mindy knew that at the time. About seven years later, Henry announced to Mindy’s mother that he wanted a divorce — and was planning to marry her daughter. Mindy gave birth to her second child with her stepfather, now husband, a month after their wedding.

In 1999, when Mindy was 32, Henry was discovered shot to death in his truck. Almost immediately, Henry’s nephew, James Smallwood, 23, admitted to the crime. He told police that his uncle had begun molesting him when he was 8 and, in recent months, had pressured him into having sex with Mindy for his viewing pleasure. The murder, he claimed, was Mindy’s idea. She told James that she was afraid of Henry, who often forced her to have sex with other men. She wanted her husband dead and asked James to do it for her.

It was a salacious story intended to shock viewers, and it did. “So the mom is the grandmother to her daughter’s kids and the mother-in-law to her ex-husband and Mindy’s brother is the uncle/brother to her sister’s kids and he is her brother/stepchild to Mindy?” wrote an incredulous Snapped fan online. “Sorry, I can’t process this shit. And I am only 11 minutes into this episode but I had to tell somebody.”

Around the same time as the episode bearing her name aired, Mindy was watching television inside her cell at Mark Luttrell Correctional Center (MLCC) in Memphis. By this point, she had been incarcerated for almost 14 years, serving a life sentence for first-degree murder. Mindy liked scary movies, but her cellmate Francine hated them, so they usually settled on lighter fare like the Golden Girls or The Simpsons or a football game if the Dallas Cowboys were playing. Mindy had never seen an episode of Snapped. To her recollection, she’d hadn’t even heard of the show.

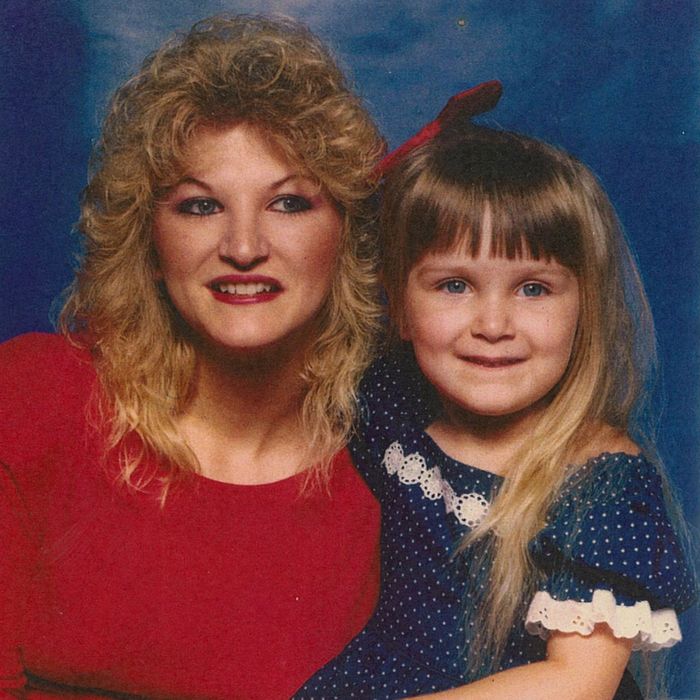

The next morning, Mindy learned she had been featured on Snapped from a correctional officer who happened to have caught the episode as it aired. Mindy then called her daughter, Angel, who was distraught. Months earlier, at her mother’s request, the 20-something had done a short taped interview for Jupiter Entertainment, a production company based in Knoxville. Angel wasn’t aware the interview was for the show Snapped, she later told me. If Jupiter had specified the name of the show in the release she signed, Angel hadn’t noticed.

“Mama,” Mindy recalled Angel saying, “they made you look like you are bad.”

When Oxygen, a cable-television channel aimed at women, first aired Snapped in 2004, it billed the series as a challenge to traditional assumptions about women and their capacity for violence. According to the original marketing material, the series would prove that there’s “something far more sinister to the fairer sex than ‘sugar and spice and everything nice.’” A gimmicky quiz on the show’s website urged fans to examine eight women’s faces and try to guess which one was a killer.

Today, Snapped is Oxygen’s longest-running show with more than 500 episodes and counting. Tune in on a Sunday, when reruns play for most of the day, and you’ll find women of all ages and races and backgrounds planning murder, committing murder, or begging other men to murder for them. What motivates them? On the show, they usually fall into one of three buckets: crazy, money hungry, or scorned. But a closer examination of the series reveals another common factor: traumatic experiences of domestic violence and sexual abuse.

While not every woman on Snapped is a victim of gendered violence, many are. Take Gail Bennett, episode No. 39, who was raped by a sheriff in the hours after she killed her husband in self-defense; Michelle Byrom, episode No. 305, a woman with mental illness who was convicted of killing her abusive husband and put on death row despite a confession from her son; Kelly Forbes, episode No. 110, who says her husband was attempting to strangle her with an electrical cord when she killed him, and Sarah Gonzales-McLinn, episode No. 307, who killed her alleged rapist.

When Snapped first aired, Zak Weisfeld, a supervising producer at the time, stated that the show would not focus on domestic-violence victims. “These are not the old stereotypes of battered women who are trying to defend themselves,” he said. “This is the dark side of female empowerment. This is not syrupy, and these women are not sympathetic.” But a show about women who kill was always going to be a show about domestic violence. Murder is mostly the domain of men; they commit more than 90 percent of all homicides and compose 80 percent of all victims. Only around 5 percent of male murder victims are killed by an intimate partner. And while there are no reliable statistics on the number of women who are in prison for killing an abusive spouse, studies have consistently found that most women who use violence in intimate heterosexual relationships are themselves victimized by their partners. To summarize: Women don’t kill their partners very often, and when they do, it’s not surprising to find that the woman was abused prior to the murder.

Recognizing that Snapped would undoubtedly narrow its lens on domestic-violence victims in its search for cases, feminist activists tried to get the show canceled when it first aired. At the time, Andrea Yacka-Bible worked to educate the public and policy-makers on the link between violence in women’s lives and their involvement in crimes as part of Free Battered Women, an organization fighting to free incarcerated domestic-violence victims in California. (The group ultimately secured the release of 27 survivors serving life sentences). “To say that someone has ‘snapped’ is just not an accurate description of what we know about trauma,” Yacka-Bible said. So her group, along with the National Clearinghouse for the Defense of Battered Women, began a campaign against the show. The group wrote a letter of protest and faxed it to groups working to end domestic violence across the country, urging advocates to send it to Oxygen, as well as directly to Oprah Winfrey, who co-founded the channel. “People were not pleased with the idea that Oprah, who folks look to as a survivor of child-sex abuse,” was “connected to a series that so sensationalizes the experience of domestic violence,” said Lisalyn R. Jacobs, a member of the National Task Force to End Sexual and Domestic Violence.

Today, domestic-violence advocates continue to have objections to the show, namely, that Snapped perpetuates myths about women who kill their partners and exploits their pain for gain. “In every situation I’ve known where a survivor of domestic violence has killed their abusive partner, they had a sense that there was no choice,” said Karen Tronsgard-Scott, executive director of the Vermont Network Against Domestic and Sexual Violence. “I’ve known people who were killed, and I know people who killed. And there’s no joy in either side of it.”

Sometime in 2012 or 2013 — she isn’t sure of the exact date — Mindy received a typed letter in the mail from Jupiter Entertainment informing her that the production company was making a documentary about her case. She doesn’t recall being notified that the show was for the series Snapped, although I could not verify this, as she did not keep the correspondence. Jupiter Entertainment and NBCUniversal, the parent company of Oxygen, declined to make anyone available for an interview. While Snapped doesn’t pay subjects for interviews and doesn’t need permission to make an episode about an incarcerated woman, the producers asked Mindy for an interview and requested that her friends and family participate too. Mindy wanted to talk on-camera, she said, but the warden at MLCC rejected the request. Still, Mindy convinced her mother and her daughter, Angel, to sit down with producers.

Her initial reaction to the letter was hope, she told me on a recent phone call from prison. “I felt like finally that I would get to tell my side of the story,” she said. “It was my opportunity to have a voice.” She didn’t testify at her criminal trial, a decision born of fear that she’d fall to pieces on the stand. Still, she was shocked when her defense attorney rested his case without calling a single witness on her behalf. By the time she was contacted by Jupiter Entertainment, she had spent years in anguish over the fact that she didn’t have the opportunity to speak out about the circumstances surrounding her husband’s death. Mindy was also out of appeals and desperate for someone, anyone, to care about her situation. A TV show seemed like the perfect opportunity. “I was led to believe that they were doing a positive story about my case,” she said.

In the making of each Snapped episode, researchers track down court documents and police reports and approach key players, such as law enforcement, defense attorneys, prosecutors, and friends and family of both the incarcerated woman and the deceased person, to give firsthand accounts. According to a source close to the show, the goal of every episode is to examine how the investigation moved forward, how the women ended up being convicted, and the psychological and emotional journeys of those directly involved. The show only focuses on adjudicated cases, the source said, and strives for as much balance as possible.

Still, most episodes rely heavily on interviews with police and prosecutors, who are treated as trusted, reliable, and objective primary sources. “Police and prosecutors lie all the time, they withhold evidence all the time, they shift and they shape narratives to fit their intended outcome,” said Scott Hechinger, a former public defender who now directs Zealous, a national initiative working to change the conversation around safety and justice. “True-crime shows depict the prosecutor’s narrative as the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth — but it is just one version of the events.”

While Mindy was eager for the attention, not all women approached by Snapped are equally excited. One incarcerated woman, who asked to use the pseudonym Kaiya to protect her privacy, recalled the fear she felt when she got a letter from Jupiter Entertainment telling her that she would be the subject of a Snapped episode. She found the tone of the correspondence intimidating and felt it included a subtle threat to participate or else. “We do not aim to make anyone out to be monsters or demonize them; our goal is to have viewers relate to them,” the researcher wrote to her. Still, if “we can only interview people who are pro-prosecution, the emotional tone of the show may seem unsympathetic.”

Kaiya, who was convicted of second-degree murder for killing her abusive husband and sentenced to ten years in prison, wondered how a short television program, designed to entertain, could possibly grapple with the totality of her and her husband’s life. “My husband was my lover, my friend, comforter — he was also my captor, my abuser, my rapist — the giver and taker of all things,” she wrote. “I never meant to hurt anyone, I’m sure my husband never meant to hurt me or my [child]. He needed help, we needed help, and we just didn’t know how or where to get it.” She also worried about the show’s ripple effect, stirring up old wounds and turning her family’s pain into a source of gossip for their co-workers and neighbors. While to her knowledge, Snapped did not ultimately pursue her case, for months she worried about how the potential episode would affect her children and her husband’s family, as well as her own chances of parole down the line.

I corresponded with another incarcerated woman, Nancy Seaman, who declined to participate in the making of the Snapped episode about her. Nancy is currently serving a life sentence in Michigan for the murder of her husband, who she says physically abused her throughout their 31-year marriage. At the time of the incident, Nancy was attempting to leave the relationship and had bought a condominium in secret. She maintains that she killed him in self-defense after he found out about her plans to leave him and violently attacked her. At trial, friends and family testified to having seen her with bruises and other injuries. But the jurors dismissed her claims, believing that she didn’t fit the profile of a typical domestic-violence victim. In an astonishing turn of events, the judge who presided over her trial is currently fighting for her release, arguing that jurors didn’t get the whole story.

Nancy chastised Snapped, which aired the episode about her on February 19, 2012, for focusing on the salacious and titillating details of her crime, instead of using its platform to address damaging myths about how domestic-violence victims should act. “They didn’t tell a story of a woman who was a kind, loyal, gentle person, a devoted and faithful wife, loving mother, and award-winning teacher. No … they portrayed me as some ax-wielding crazy who ‘snapped’ and killed her husband. That’s not what happened,” she wrote. “These vultures preyed on the wounded and vulnerable victims of my personal tragedy. They picked at the carcass of our shattered lives and feasted on our pain and misery — solely for their own personal profit.”

Mindy, 54, is now 20 years into a life sentence at the West Tennessee State Penitentiary. Most days, she works on the yard crew — riding a lawn mower, running a weed-eater, and gardening in the flower bed. “I like all of it,” she said. She also takes group-therapy classes, often centering around childhood trauma, grief management, and domestic violence.

I learned her story piecemeal over a series of phone calls, emails, and letters sent during the pandemic. I was also able to review a psychiatric evaluation conducted after Mindy’s arrest, affidavits from her family attesting to her claims, her parole application, and over a dozen letters from correctional officers describing her behavior while incarcerated.

Henry, the man whose death she is in prison for, began molesting her when she was 6, she said. “I can remember being told that that’s what all little girls did with their daddies.” When she became old enough to say no because it didn’t feel right, she told me, Henry would threaten to kill her as well as her mother and younger brother. By 14, Henry would rape her every time they were alone. Mindy’s mother, in an affidavit, said that she worked at night and wasn’t aware of the sexual abuse. “I regret that I didn’t pay closer attention to the situation when she was growing up,” she wrote. “I know that this is no excuse but back then abuse like that wasn’t talked about like it is today.”

After Mindy got pregnant with Henry’s child, Mindy said, she internalized the belief that she would never be free of him. I asked her why she married him, given the years of sexual abuse and threats of physical harm. To her, she explained, it seemed the safest option. “I felt that I had nowhere to turn and no one that I felt that I could trust,” she said. “Not only did I have my mother and brother to protect, but I had my own daughter to protect as well.”

Two factors coalesced in the months leading up to Henry’s death. James, Henry’s nephew, was temporarily living with the couple and observed their fights. As a child, James had been molested by Henry. Now an adult, Henry still seemed to have some sort of power over him. According to Mindy, Henry forced his nephew and Mindy to have sex in front of him. This wasn’t a new occurrence for Mindy. Henry had forced her to have sex with her own mother, as well as other men. Mindy’s half-brother recalled an incident where Henry tried to make him have sex with Mindy, saying that “pu**y was pu**y.” He cried and begged his father not to make him. Eventually, his father left the room.

The other factor was that Mindy’s daughter, Angel, was almost the same age that Mindy was when Henry first started raping her. Mindy was convinced that Henry was going to start sexually abusing her daughter and didn’t feel she could protect her, she said. She was afraid of Henry, who would take out his gun during fights and threaten to kill her. She admits talking to James about her fears and recalls James telling her that he was going to take care of it. She says she didn’t think he was serious. “I can honestly say that I should have told someone of authority what James was planning to do,” she wrote in her application for clemency. “Instead, I stood by and let a man’s life be taken.”

I sent her a copy of the transcript of the Snapped episode to hear her thoughts on how she had been portrayed; she’s still never watched the episode. Mindy sat with the transcript for a week or so before we were able to speak; a new coronavirus lockdown had drastically reduced how much time she was allowed out of her cell. When I finally reached her, she said she was disappointed and hurt. “They made it out like it was just some big sex scandal,” she said. The narrator kept emphasizing how unemotional she was after the death, she said, like it was evidence that she was a cold-blooded killer. After Henry died, Mindy told me, she went through a range of emotions — fear, anger, sadness, relief, but most immediately shock. “I hated that a mother’s son was taken away, a brother was taken away, an uncle, a daddy, a grandpa,” Mindy said. “But at the same time, I didn’t deserve to be treated like that. I was a child, an innocent child, my innocence was taken from me. So, I mean, how was I supposed to feel? I wasn’t necessarily happy. But I was, I guess, relieved in a sense that I didn’t have to go through that anymore.”

It seemed to her that Snapped had simply repeated the story told by the prosecution without probing deeper. The episode included the abuse allegations, but they were treated as incidental instead of at the heart of the issue. While the district attorney and various police officers spoke 60 times in the episode, a psychologist brought in to help explain Mindy’s behavior spoke only three times.

Angel, Mindy’s daughter, was disheartened by the episode as well, and it had made her suspicious of the media in general. “I didn’t know it was for Snapped until after everything was all said and done, because otherwise I probably wouldn’t have done that,” she said. “Nobody wants to be on that show.” She was in her 20s at the time and not particularly media savvy. “They actually made it more enticing because … they actually offered to pay for pictures,” she said. At the time, she thought she was helping get the truth about her mom out, and the prospect of getting some extra cash for dredging up a few old photos was hard to pass up.

In recent years, the public has begun to look at cases like Mindy’s with fresh eyes. Cyntoia Brown, who was sentenced to life in prison for killing a man while she was a teenage sex-trafficking victim, received clemency in 2019 after celebrities and advocates rallied for her release. Bresha Meadows, who killed her abusive father when she was 14, narrowly escaped decades in prison after her case sparked a national outcry and even inspired a Talib Kweli song. It is not hard to imagine how Snapped might have memorialized their stories, or how many women like them could be found in the Snapped archives.

The tide is changing for Mindy too. On December 2, Republican governor Bill Lee granted her executive clemency — reducing her life sentence to make her immediately eligible for parole. She expects to have a parole hearing in the next few months.

“I’m still trying to process everything,” she said when I reached her on the phone. She learned of Lee’s decision from the warden, who wished her well. She burst into tears, then went to tell her roommate. “We jumped and hollered and squealed,” she said. Mindy is hopeful that she will be released soon and can finally rejoin her children.

I asked Mindy what a television docudrama on her life would include if she was in charge of it. It would start when she was a child, she said, lingering in those early years so that the audience could understand what it was like, in that house, being abused by a man she could not escape, and the horror and resignation she felt when she realized she would never be free of him. It would have asked critical questions about her treatment by the criminal-justice system, showing how she was interrogated by police without counsel and how lost she was at trial. It would have shown how she still cried at night and asked God’s forgiveness. Wasn’t that a story worth telling?