When you talk to people about Jell-O, associations vary. One friend thought of hospitals: Why do they feed sick people a bowlful of sugar? My mom asked if Jell-O was making a comeback, citing Costco’s premade Jell-O shots. A lot of people mentioned the 1950s. No one said “yum.”

Nonetheless, I informed my mother that yes, Jell-O is indeed making a comeback. Today, Solid Wiggles — a business with a decidedly millennial aesthetic operating out of Kit in Brooklyn and online through Goldbelly — creates Jell-O cakes that are often boozy and always beautiful, selling for $100ish a pop. Popular food artist Jen Monroe perfected little gelatin sky cubes for a recent Timberland event. Chef Laila Gohar made berry-filled molds for a fahncy luncheon in Milan. Lexie Park makes jelly creations in Los Angeles, and the Jellyologist sells Jell-O kits out of New Zealand, including this Xmas Table Stunner. So why, more than a half-century past its heyday, is the retro treat having a resurgence? Like too many things today, it has a lot to do with Instagram.

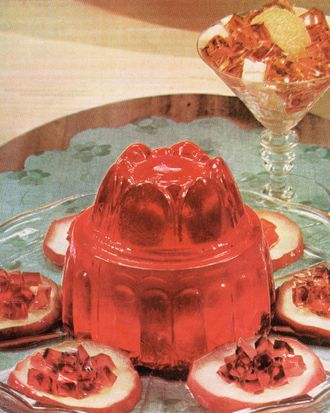

Gelatin, of course, predates Instagram by more than a century. Highly wrought gelatin centerpieces were popular as far back as medieval Europe, but instant gelatin, otherwise known as Jell-O, wasn’t packaged and sold until 1897, when a couple trademarked the brand name. The instant mixture was used to encase salads and leftovers and offered a clean, tidy look (along with an indication of wealth) — something lauded by both turn-of-the-century cooks and their Victorian counterparts. In the early 20th century, Jell-O sales picked up thanks to gendered and quick-pivoting marketing efforts — first positioning it as an affordable yet refined way to preserve wartime rations and then, as sweet iterations gained steam, as a light dinner-party dessert. In the ’50s, there was a shift toward intricate food presentation, and gelatin proved the ideal case study, melding the instant-food fad with domestic idealism. But by the ’70s, the buzz had quieted, and Jell-O was largely relegated to children’s lunch boxes and hospital trays. There was a brief uptick in sales in the ’90s, when Jell-O leveraged recognizable names to front its commercials, but the mass appeal was undoubtedly gone.

Lately, though, I’ve noticed a steady stream of jiggly treats in my feed, each one a feast for the eyes but, I’d wager, less so for the belly. “There’s this currency of food imagery that’s taken hold in the last couple of years that doesn’t have that much to do with the experience of eating,” explains Monroe of @badtaste.biz. It seems the distinction between food and art has worn thin, and as we near the end of 2021, the internet is rife with holiday-party documentation that toes this line.

It’s worth noting that queer and female artists have been working with Jell-O for years, toying with its historical ties to binary gender roles, among other more nuanced implications (straightness, sacrifice, sensuality). As the New York Times reported in 2018, Alison Kuo performed a piece in which she “caressed, slapped and shook a translucent blob of Jell-O.” Sharona Franklin’s gelatin sculptures, which garnered internet buzz the following year, addressed disability and living with chronic illness. And around the same time, creative duo Lazy Mom crafted gelatin molds that encased candy and money. Even today, Jell-O is a medium for artists like Leanne Rodriguez, who makes and sells lamps that resemble (mostly) savory gelatin molds. In a sense, the art world primed us for the resurgence of Jell-O, readying our palettes and our social feeds for the flavors and textures to come.

Perhaps some of this surge in food-posting is related to the pandemic. Last year, as the virus spread and we were forced inside, people took on new domestic habits like cooking. In this move toward home economics, many strayed from the hypercurated ethos of wellness and embraced food as a source of comfort or nostalgia. For some, it culminated in baking sourdough and indulging in whole milk. Others attempted to level up their Instagram feeds in a way that felt reminiscent of the mid-century proclivity for culinary extravagance (see this ornately carved butter). Over the past two years, things like beet-dyed deviled eggs and minimal tablescapes have replaced neat, pristine cakes and over-the-top fine dining. No matter how you slice it, carve it, or dye it, there’s a palpable return to Americana in the culinary world, maybe even a reclaiming — so it’s no wonder Jell-O has found a home.

But it is valid to wonder whether we’re prioritizing presentation over the sensory experience of eating. Monroe grapples with her relationship to Instagram — and understandably so (though she says she’s immensely grateful for the career it’s afforded her). Food existing on the internet inherently plays into some kind of capitalist agenda, living in a state divorced from tangible consumption or enjoyment. Lately, a slew of social-media campaigns have monetized this fetishization of food. Parade, the buzzy underwear brand, frequently commissions food artists in its marketing efforts. Independent fashion label Pearle Knits channeled ’50s cuisine for a recent campaign. And Park, the aforementioned Jell-O artist, just made a mold for Hendrick’s Gin. We’re using food to sell things rather than to satiate ourselves (or at best, to do both).

When Monroe is asked to use gelatin for events, which happens more and more as of late, she often pushes back because “a lot of it is probably going to end up in the trash.”

Jena Derman and Jack Schramm of Solid Wiggles have internalized the significance of presentation but also refuse to skimp on taste appeal. Plus things change when you add alcohol to the equation. “We’ve found that people who say ‘Oh, I’m not into Jell-O’ will still have a Jell-O shot,” says Derman. But that doesn’t mean they rely too heavily on the kitschiness baked into the idea of a gourmet Jell-O shot. “We spend a lot of time crafting the flavor combinations and figuring out how to make them as bright and pointed as possible,” Derman says.

The takeaway could be optimistic (“Wellness is over — food is fun again!”) or nihilistic (“Not even dessert is safe from the ever greedy clutches of capitalism”). Or perhaps both can be true. Either way, fans of the Jell-O shot can rejoice — Solid Wiggles has seen a fall boom, much of which can be attributed to winter parties and holiday gifting, and the duo looks forward to continuing to experiment with thematic flavors like its Boozy Showstopper. As for the next internet food craze? Monroe predicts it will be Victorian ices, which are highly ornate and sculptural ice-cream molds. Her reasoning is simple enough not to require an entire think piece: “People are generally enthusiastic about eating ice cream.”