This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

What readerly experience matches the pleasure of a well-executed, well-deserved takedown? When the critic is sharp enough, the subject praise-glutted enough, the results are exquisite — succulent, tart, worth any mess.

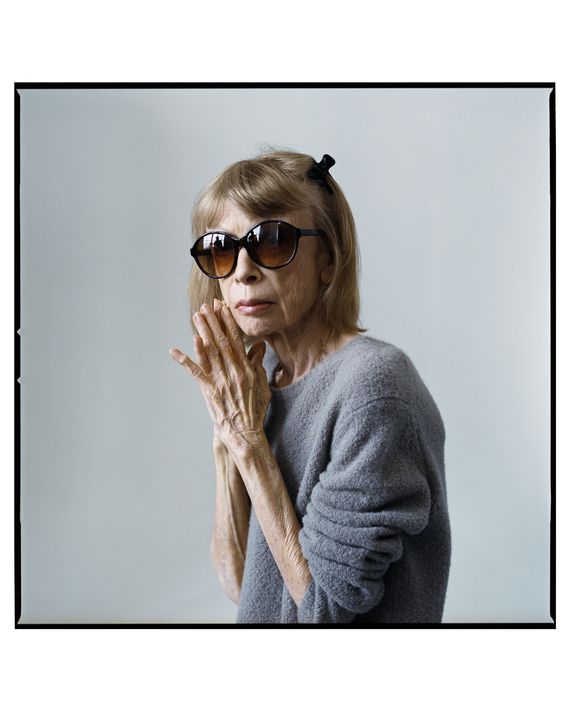

Forty-two years ago, Joan Didion — who died today at 87 — delivered one such delectable specimen. “Letter From ‘Manhattan’” was the restrained headline that appeared above her 1979 New York Review of Books essay on Woody Allen’s late-’70s oeuvre. And, if only in a certain sense, the essay that followed was restrained as well. Didion was not unleashing a tirade; tirades were not her style. Rather, she was describing — with exasperated precision — a body of work whose popularity she professed to find “interesting, and rather astonishing.” Allen’s characters possess “the false and desperate knowingness of the smartest kid in the class,” Didion wrote. In their preoccupations and pretensions, they were overgrown teenagers:

These faux adults of Woody Allen’s have dinner at Elaine’s, and argue art versus ethics. They share sodas, and wonder “what love is.” They have “interesting” occupations, none of which intrudes in any serious way on their dating. Many characters in these pictures “write,” usually on tape recorders. In Manhattan, Woody Allen quits his job as a television writer and is later seen dictating an “idea” for a short story, an idea which, I am afraid, is also the “idea” for the picture itself: “People in Manhattan are constantly creating these real unnecessary neurotic problems for themselves that keep them from dealing with more terrifying unsolvable problems about the universe.”

“What love is”: the scare quotes are chilling in their absolute disdain. This gives you the general flavor of the review, which is memorable — but the real coup de grâce, and the reason this essay most often comes to mind for me, was something that arrived only later. A few months after Didion’s review appeared, the NYRB published a selection of responses from readers. These readers were not pleased. Randolph D. Pope of Dartmouth College, no stranger to sarcasm, congratulated Didion on providing “a perfect example of how a mind too full with culture is unable to understand humor.” Roger Hurwitz (MIT) advised that she would “do better to be alarmed by than morally superior to the attitudes, concerns and mores Mr. Allen’s characters reflect.” John Romano (Columbia) spent 647 words chastising her for — among other offenses — treating Allen’s characters’ brand of self-absorption as tiresome and distinctly contemporary, rather than placing them in an intellectual lineage that stretched back centuries.

The NYRB also published Didion’s response to these letters. It reads, in its entirety, “Oh, wow.”

Reactions like Randolph D. Pope’s or John Romano’s are hardly what any writer hopes for when sending a piece of prose into the world. Nonetheless, such reactions do arrive, and with them the temptation to reply — that is, to defend one’s self somehow. This impulse is not always doomed, but it usually is.

Which is, at least in part, what makes Didion’s response impressive. I think about this (as the Cut’s column would have it) a lot. I think about it whenever I say “Wow.” And I think about it now, looking back over Joan Didion’s career, a career that gave rise to countless lines that in the years since I encountered them have “never been entirely absent from my inner eye” or ear, as Didion once wrote of the Hoover Dam.

“Oh, wow”: unimpressed, unperturbed, over- but also underwhelmed. A “wow” delivered in the same spirit as Didion’s claim to find it “astonishing” that anybody actually liked the characters in Manhattan — as if bearing witness to behavior so pathetic as to be stunning. Roger Hurwitz of MIT is getting himself all worked up about “objective decadence cum subjective meaninglessness.” Didion is watching like he’s a particularly large beetle rolled on its back.

It is a response that distills the Didion persona down to five letters. She was ever the observer, surveying human folly from a deliberate distance, amazed and not amazed by what she saw. This was the posture she adopted when meeting a Haight-Ashbury 5-year-old on acid. “The five-year-old’s name is Susan, and she tells me she is in High Kindergarten,” Didion wrote in the title essay of Slouching Towards Bethlehem. “I start to ask if any of the other children in High Kindergarten get stoned, but I falter at the key words.” Years later, in an interview for his documentary on her life, Griffin Dunne asked his aunt what that moment was like. “Well, it was—” Didion said, and paused. “Let me tell you, it was gold.” (Oh, wow.)

Her mode was cool scrutiny even when the object was herself. She catalogued her assorted frailties, physical and otherwise, her habits, her predilections — and her marriage to John Gregory Dunne, a subject that in The Year of Magical Thinking drew a tide of late-career popularity and acclaim. In 1969, at the Royal Hawaiian, she’d told the reader as if offhand that she was in Honolulu “in lieu of filing for divorce.” In 2005, she brought the same combination of disclosure and distance to a grief memoir, and the effect was wrenching, rather than chilly or detached: the gulf between the mute immensity of loss and the painstaking precision of her voice gave the book its power. After Dunne’s fatal heart attack, at the hospital, a social-worker doctor called Didion “a cool customer,” she wrote in the book. Maybe so, but she also observed her own inability to clear her husband’s closet, harboring the irrational conviction that he’d return and need his shoes.

The pose was always self-aware. And while it was her essence as a writer and her great asset as a public figure, Didion’s aloofness was also what drove her critics nuts. It lent itself to caricature, as if she were her packing list personified: style and nothing more. Her finely tuned taste (and skill in crafting her own image) encouraged those inclined to see her in this way. In “Letter from ‘Manhattan,’” Didion described Allen’s collection of “modishly eclectic” cultural references as “the ultimate consumer report,” a litany of proper nouns standing in for an identity. An irony of her career was that she became the exact sort of figure fans used in this way — as an emblem of good taste, a fixture of the cultural consumer reports that proliferated via social media.

Shortly after the Allen piece came out, Didion herself was the subject of a scalding takedown. In the essay “Joan Didion: Only Disconnect,” Barbara Grizzuti Harrison took her to task for a tendency to traffic in what Allen had called “unnecessary neurotic problems.” Didion had written that, in the ’60s, “no one at all seemed to have any memory or mooring,” Harrison notes — “but to what is she moored? What she is moored to, of course, is her angst. And her angst is not the still point of the turning world.” Harrison indicted Didion as a reactionary and a snob, one whose “art of deflation is never put to use against those in power.” This was not an unreasonable critique of the onetime Goldwater girl who’d written The White Album and Slouching Towards Bethlehem (and, for the Didion-giddy college freshman I was on first encountering Harrison’s essay, it was a necessary corrective). But it also arrived at a moment that can be understood as a “hinge” in Didion’s career, the moment when she was moving from the personal writing that had made her famous to the political commentary and international reporting she’d go on to contribute to the New York Review of Books. There she turned her eye from addled hippies and tacky housewives to subjects like American political interference overseas, the media spectacle that surrounded the Central Park Jogger, and post-9/11 jingoism. The mode she’d honed in the ’60s and ’70s — merciless, precise, deliberately distant — could also take down larger game.

Thanks to her embrace of the first-person, Didion has long offered something of a model for the generation of writers who have come of age writing online. She, too, wrote prose yoked to a public persona; she, too, took her subjectivity as a starting point. What’s changed, of course, is the sense of remove — Didion’s commitment to the posture of an observer, in contrast to many of her heirs’ sense of themselves as directly engaged advocates.

But I hope part of her legacy can be a renewed appreciation for distance as a critical and rhetorical tool. The power of an ice-cold, unflinching gaze on antagonists? Oh, wow.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the January 3, 2021, issue of New York Magazine.