There are two lines in Xochitl Gonzalez’s debut novel, Olga Dies Dreaming, that have not left me in days. The first is a simple observation that Olga Isabel Acevedo, Gonzalez’s protagonist, makes about a lover: “He was soothing. Like sweet fried plantains.” This, I thought, is how love feels to me, too. The second is machete-sharp and made my blood run cold. Her father says, “The United States made Puerto Rico’s handcuffs, but it was other Puerto Ricans who helped put them on.” This, I thought, is exactly why my people remain crushed under the weight of colonization after nearly 125 years.

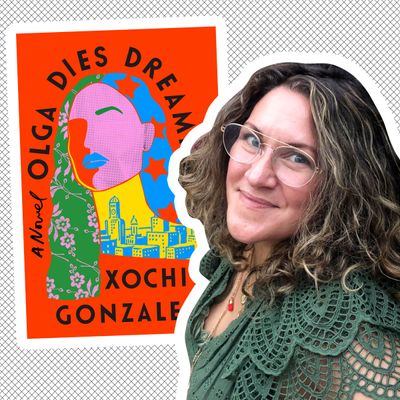

That a novel could marry such different facets and be everything at once —a rom-com, a political thriller, a family drama, and an unflinching look at Puerto Ricanness that tackles gentrification, colonialism, capitalism, corruption, machismo, ambition, and queerness — seems insane. And yet Gonzalez is triumphant (as even Hulu has recognized, ordering a pilot starring Aubrey Plaza before the novel even went to print). That’s because, once you start, Olga and her tribe don’t let you go.

She is an ambitious 40-year-old named after a Puerto Rican revolutionary who climbed from a working-class childhood in Sunset Park to being the wedding planner of choice for New York’s ultrarich. Her brother, Prieto, is a beloved and deeply closeted Brooklyn congressman trying, and failing, to do his best for his community and ancestral home. It’s not exactly the future that their mother, Blanca, a Young Lords alumna who walked out on her children to fight for liberation around the world, imagined for either of them. As Hurricane Maria approaches Puerto Rico with devastating force, Blanca returns, sending the siblings’ lives into chaos.

The ending, which Gonzalez and I discussed at length, is unlike anything I’ve read in recent years and the only way to explain my reaction is “eah puñeta.” Below, she tells us about how her novel is a love letter to Brooklyn and Puerto Rico, the dissonance that comes with becoming a writer at age 40, and the ways in which she tried to remind people that the United States still has a “fucking colony.”

You have said you came up with Olga Dies Dreaming while you were on a train reading Naomi Klein’s The Battle for Paradise and listening to Hurray for the Riff Raff. (I’ve listened to “Rican Beach” and “Pa’lante” on the N train more times than I can count.) Tell me more about how this book came to be.

I started out writing nonfiction because I didn’t think I could be a fiction writer. I wrote a 20-something-page essay that was about my experiences with my own mother, who had been an activist. But I did not live with her. I went to live with my grandparents when I was 3. We had this strange relationship where she would come in and out, and it was hovering and yet at the same time not really there. The original essay was about being at this wedding-planning convention and trying to see my mother and her not answering my calls. Everybody kept being like, “This is so complicated.” But I was intrigued by her going unionizing all over Latin America, fighting apartheid, and trying to get reparations for all the women who had been sterilized in Puerto Rico, while I’m talking at a wedding conference.

When I was in my 20s, novels were very broad. There were these big, crazy books, where lots of weird stuff happens and you’re going to many places. I wanted to write a book like that. When I decided to try and write fiction, I would write these stories about these different characters, but then I realized they were the same character: Single women who were around 40, living in gentrified Brooklyn, and not quite fitting in, even though this is their hometown. That day, I was on the train, and suddenly I had Olga in mind.

You’ve called this a love letter to Brooklyn, but it also feels like a love letter to the island. What parallels do you see between those places and how did they influence you?

Growing up Ricanness was so ingrained in Brooklyn and in New York, and it’s funny, because as gentrification has changed this place, it has created a second diaspora: So many Puerto Ricans who were entrenched in New York had to go to Pennsylvania, to New Jersey. That is being lost, too. Growing up, though, I think I was never good at being a good New York Puerto Rican. I was not a paradegoer, do you know what I mean? There was also this weird thing where I grew up feeling so Puerto Rican and then I’ve not spent enough time there — a very common New York thing, especially if you didn’t have a lot of money. The book was a love letter to my culture, if that makes sense. I was never going to be the person waving a big flag. That’s just not my personality. But it doesn’t mean that there wasn’t a flag waving in my heart.

When somebody asks me what the book is about, I always say resilience. My whole life, because I’ve had some biographical parallels to Olga, people would say, “Oh, you’re such a resilient person.” And when I was writing this book, I was like, Oh, that’s my genetic inheritance. I think what I see as a parallel in both places, though, is that it was a place that was utilitarian. They’re like, We’ll put a jail here; we’ll put a navy yard here. Nobody really cares about Brooklyn. Oh, we’ll put a military base in Puerto Rico. We’ll have some pharmaceutical companies, use it for a port.

Then suddenly, one day, somebody decides that it has value, and it becomes a systemic decimation of a people. Like, Well, let’s literally just make it unlivable. There’s a true exploitation and a devaluing of people.

Olga and Pietro captured very beautifully the impossibility of being born in the diaspora. You have this very special connection to Puerto Rico, but it’s a painful connection, because maybe you don’t visit, or maybe you don’t speak Spanish. You feel very Puerto Rican, then you go down there, and you don’t belong. But then there’s also the pain of being in the U.S., and in many ways, you are never fully accepted as an American.

When I’ve been doing interviews, people will talk about them as an immigrant family, and I’m like, “But no.” I get the sentiment, but it is neither here nor there. My dad’s side of the family was from the Mexican border, and literally a border was placed. Nobody on either side of my family chose to be American. It was thrust upon them. That also gives you a very different sentiment of being here. In New York, so often, you were grouped into the shittiest areas. You’re given second-class citizenship on the island, and you’re actually given second-class citizenship on the mainland too. What the Young Lords were doing was because they weren’t picking up their fucking trash. They had lead poisoning in their apartment buildings in these neighborhoods.

I think that is why I wanted Blanca, their mom, there. I wanted to reconnect us to this idea of a legacy of fighting. I started the book before the protests in the summer of 2019, and I got to write about it in the end. I wanted all that history there because we don’t get taught our history. Then we forget, and we’re learning together. That disconnect is a way of disempowering us.

The ousting of Puerto Rico’s governor Ricardo Rosselló in 2019 was deeply connected to what happened with Hurricane Maria, which is a main part of the book. Those chapters brought back a lot of feelings of pain and helplessness. I felt I was again at home in Queens desperately trying to contact my parents while watching all those terrifying Facebook Lives, seeing the devastation in real time before the feed cuts out, wondering if that person was still alive.

I remember the videos and feeling terrified. I write Maria as an angry lover, and she parallels Blanca. She is this woman who has a power that you are powerless against, who can come to you. What I tried to call attention to is that, yes, it’s a natural phenomenon, but it’s not like a tornado that comes out of nowhere. There was so much that could have been done by the government to prepare better. In terms of the lived experience, there was this feeling like you are at a violent person’s will, and it has no rhyme or reason. It’s also something that people were watching but other people were living. We glimpse the horror, but somebody is living it. It’s this thing that is just gawked at.

The existences of Olga, Prieto, and Blanca are so tightly linked to colonization and imperialism. You can’t erase that perspective. One thing that I found interesting is that even with that awareness, the book doesn’t have really explanatory commas. You’re not saying, “Olga’s cousin Mabel was drunk on coquito, comma, the Puerto Rican eggnog.” The first one I found was like 70 pages in, when Matteo and Olga are at Sylvia’s. Matteo goes, “How did you become a wedding planner when your mom was part of the Young Lords, comma, the revolutionary group?” And even then, this says more about him as a character.

I love him because he’s such a know-it-all. It’s sort of obnoxious, but he’s so Brooklyn that way: Oh, I’ll tell you a fun fact. It was a big decision of mine: I’m writing this for other women and men like me, and so I don’t need to explain anything. Then there was another part of me that was like, If I make her a wedding planner, I might be able to make people give a shit about Puerto Rico and the fact that we have a fucking colony. I was not going to write for that audience, even though I had hoped that I could lure them in. Do you know how many times I’ve had to learn somebody else’s cultural language?

One of my favorite books is The Sellout. It’s about gentrification in Los Angeles, and it’s written from a Black man’s perspective. It’s a deep, deep satire. And he does not give a shit! There are so many jokes within jokes within jokes that I don’t even get because they’re so inside baseball. Still, you can get so much out of it. In her documentary, Toni Morrison says, “I had to write to get the little white guy off my shoulder and not care that he was there.” This was Olga and Prieto’s world, and I just felt that if you’re of their world, and if I do a good enough job, you’ll figure it out. The person that it’s written for, they don’t need the explanation. I wanted you, if you were on the inside, to feel seen. It was really liberating.

You decided to become a writer at 40, so how do you process the past few years — getting into the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, the book, the Hulu pilot based on the book — compared to your previous life?

My life is so different, not just from my old life, but it’s so different from any life that I knew as an adult growing up. Sometimes I have some panic attacks. I do weird shit. I was going to have a book party, but then because of Omicron I couldn’t. And so I was like, Well, I’m going to make these little boxes for Three Kings Day to send to some of the people that would’ve been invited. It has the book and coquito. I stuffed my own gift boxes for 17 hours. I had to do the manual labor because it almost feels too luxurious to just be able to write all day.

But I think my grandparents would be very proud. It has been so much change in just a couple of years — I’m definitely still adjusting. Somebody asked me when I was doing the show, “Did you always dream of a career in film and television?” And I was like, “I dreamed of a door in my bedroom.” Literally. I was like, I’ll go to college, I’ll get a job, I’ll get an apartment — there’ll be a door in my bedroom. I always was very determined, but honestly, we had such a modest worldview that this feels a little above and beyond. But it’s a dream.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.