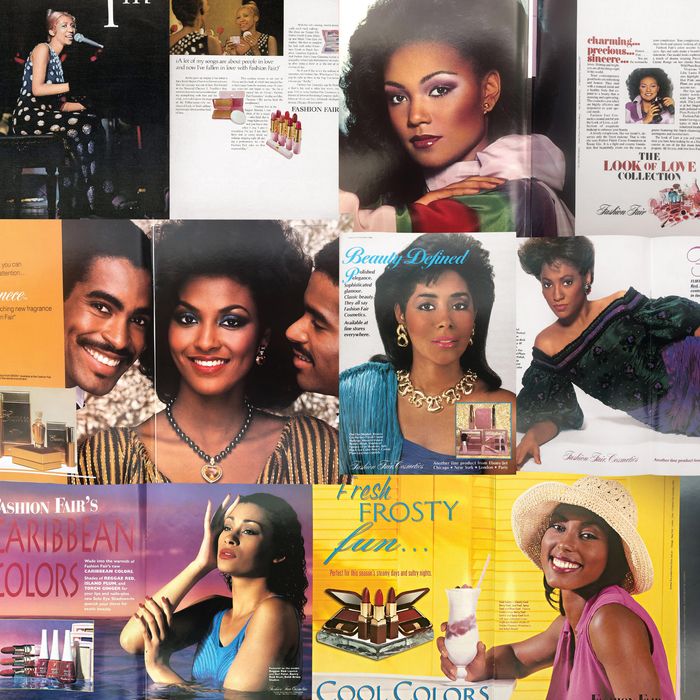

If you grew up in a Black household during the 1970s and 1980s, you might remember the ads: Leontyne Price, Judy Pace, Nancy Wilson, Natalie Cole, and others, shimmering across two-page spreads. They were often pictured gazing into a pink compact, gingerly adorning themselves, some grinning in approval and delight, others studied and focused on their application, taking care. As Aretha Franklin declared in hers, “A lot of my songs are about people in love, and now I’ve fallen in love with Fashion Fair.”

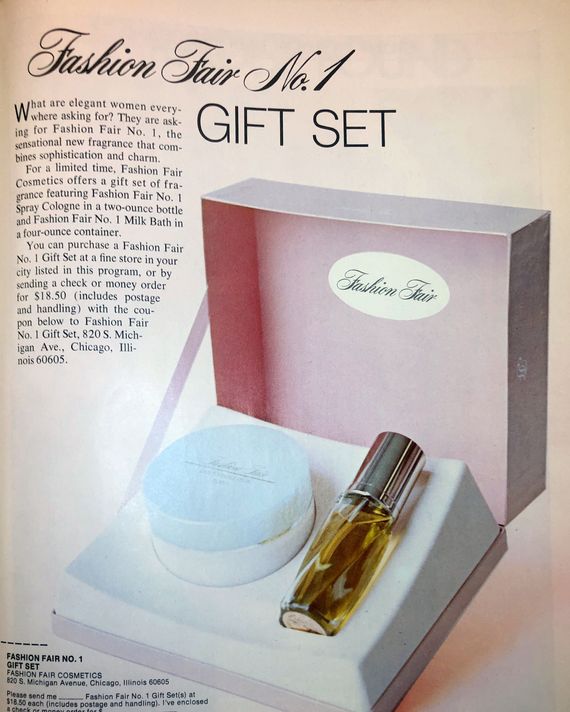

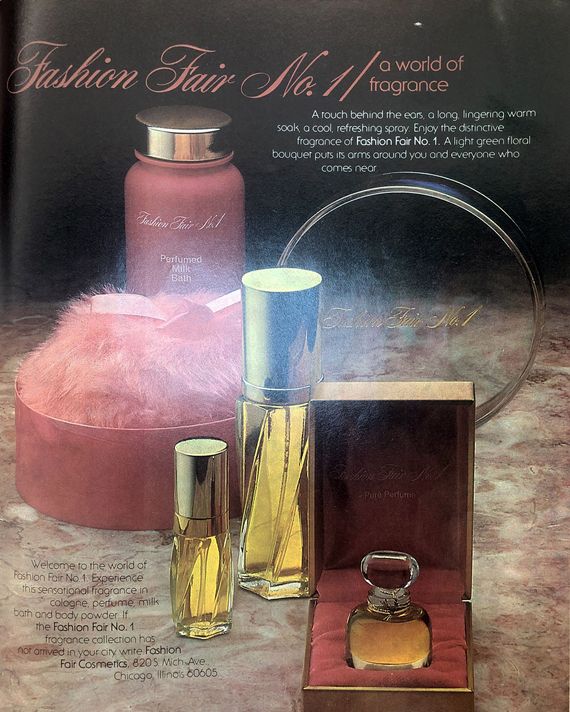

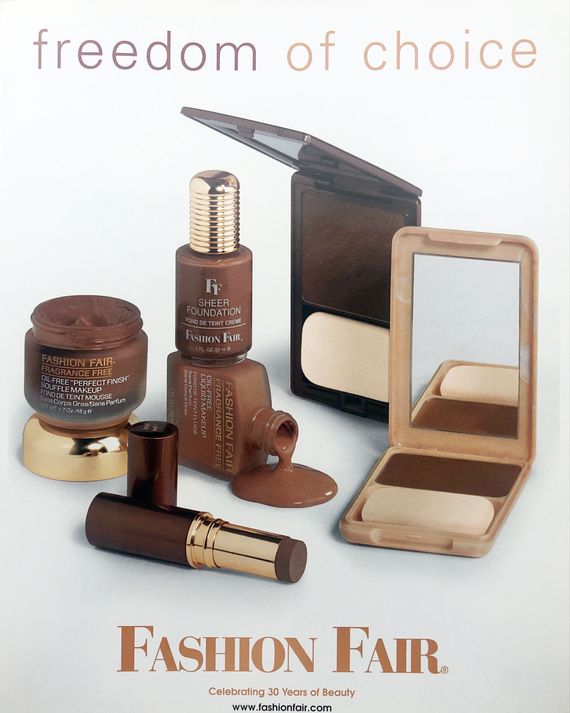

Fashion Fair was always more than just a brand of powder and lipstick. Started in 1973 by Black American media royalty — Eunice Walker Johnson, who, with her husband, John Johnson, owned the Johnson Publishing Company, home to Ebony and Jet — Fashion Fair was an extension of Eunice’s vision of bringing glamour to a Black audience underserved by the Eurocentric beauty industry. For decades, it was the go-to Black beauty brand. Then, in 2018, with no warning, no explanation, and no good-bye, Fashion Fair cosmetics disappeared. No more Moroccan Spice, Bordeaux, Cherry Wine, and Sweet Maple lipstick shades. No more Chocolate Raspberry.

Last fall, thanks to Desiree Rogers, the Obamas’ former White House social secretary — the first Black woman ever to hold that role, though she didn’t hold it for long — Fashion Fair officially relaunched in 225 Sephora stores with actress KiKi Layne as its celebrity ambassador. The new Fashion Fair is more of a reboot than a revival: vegan, fragrance free, and, with many products at $37, a premium brand fighting for relevance in an increasingly crowded marketplace. In other words, it’s not your auntie’s cosmetics line anymore.

The story of Fashion Fair starts with an empire. In 1958, the Johnson Publishing Company started an in-person brand extension and charity event called the Ebony Fashion Fair, which would travel from city to city with models of color wearing the latest looks. It was at these shows that Eunice Johnson witnessed models backstage concocting their own custom foundations to match their varying brown complexions and saw a business opportunity. Only Flori Roberts, a white-owned company launched in 1965, and the eponymous Barbara Walden, a Black-owned brand launched in 1968, made shades for brown and dark-skinned complexions. The darkest foundation mainstream cosmetics brands carried at the time were shades for olive skin, if that. In 1973, Johnson launched Fashion Fair cosmetics to fill that gap.

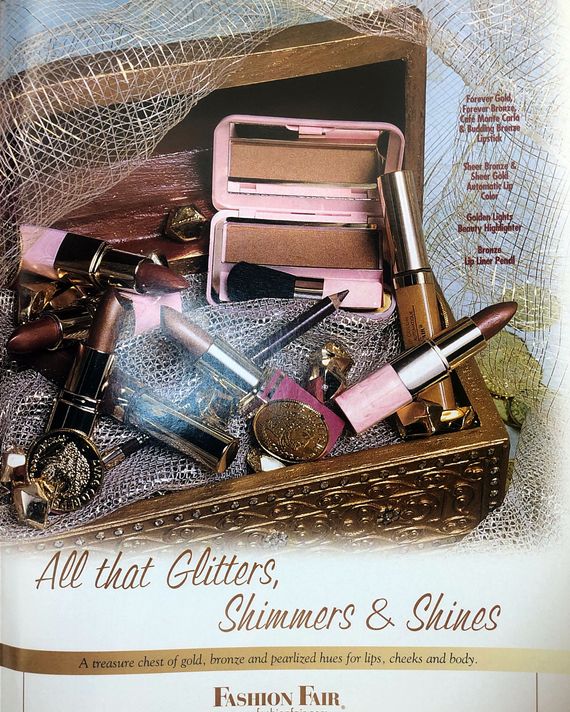

The company’s facial powders had bases in yellow, ocher, and gold, and they didn’t leave a chalky, ashen residue like other makeup. Its lipsticks included colors with warm, deep, rich undertones, introducing a wide variety of shades to department stores for the first time. Finally, women with darker complexions could pick out a foundation that matched their skin tones without having to mix. By the ’80s, other companies would follow suit. But for many years, the association with Ebony set Fashion Fair apart.

“If you said Ebony magazine, that was just sorta the endorsement for the Fashion Fair cosmetics line,” says author and image consultant Alfred Fornay, 78, who worked for JPC for 20 years, including as beauty editor of Ebony and editor-in-chief of Ebony Man. “The two were inseparable.” For many years, Fashion Fair could draw on the deep pockets of its parent company to stay competitive with the bigger, white-oriented (and -owned) cosmetics companies. It had direct access to its target audience and not just a clear understanding of its needs and culture but a hand in shaping them. Fashion Fair makeup was exclusively used for Ebony fashion and beauty photo shoots.

Those Fashion Fair ads were in every issue too, reinforcing the mission the line shared with the magazine. “Today, I feel like I’ve come full circle,” read actress and singer Diahann Carroll’s ad. “Ebony gave me my first paycheck, I’ve made the cover of three JPC magazines, and now Fashion Fair has come into my life.” In editorials and advertisements, Ebony readers saw images of women like themselves sitting in luxurious living rooms and working as professionals. The connection was clear.

Meanwhile, the Ebony Fashion Fair traveled to as many as 30 cities every year, earning more than $60 million for African American charities and funding college scholarships over its 51-year run. The day before each show, makeup artists and models would hold promotions and live tutorials at a local department store’s Fashion Fair makeup counter, and during the show itself, the announcers would remind the audience that the couture-draped models used Fashion Fair. Customers living in cities where the tour stopped would carry the Ebony Fashion Fair advertisements into the store so they could buy exactly what the models were wearing.

“We were kind of famous,” says Pamela Fernandez, 61, a model and commentator with the show for nearly 12 years, beginning in 1982. “We had all different skin tones onstage, and we would get those same different skin tones around the counter. We really connected with each other and just felt our Blackness and loved it.”

Rogers, the brand’s new co-owner (with Cheryl Mayberry McKissack, another former JPC executive), remembers the shows from her New Orleans youth. Her mother, Joyce, won a contest to model in the first show in her hometown, a fund-raiser for a local hospital, but, Rogers recalls, she “chickened out” at the last minute. For Rogers, born in 1959, her generation of young Black people came of age when Ebony Fashion Fair cosmetics were the standard of glamour. That’s what most interested her about reviving the line: the rare opportunity to build on its legacy. “I don’t want to be greedy,” Rogers says. “But I want to create a company of scale that lives on well past my lifetime where we’re the best of the best.”

A well-connected corporate executive with a Harvard M.B.A. and a background in utilities, insurance, tourism, politics, and publishing, Rogers has often been drawn to ambitious, and sometimes contentious, makeovers of stagnant institutions. During her time in the White House, she opened up the social life of the presidency in unprecedented ways. In the process, she became well known herself, appearing on best-dressed lists and in glossy magazines. Her high profile was a departure from the social secretaries before her, and sometimes she had to be asked to tone it down. On one occasion, Michelle Obama — her friend of many years — reportedly asked Rogers not to go to a splashy MTV event even though she was already on her way there. Her time in office lasted only 13 months; an abrupt resignation came after two party crashers breached security at a state dinner in 2009. As she observed to the New York Times in 2010, Washington “is an environment where someone is always looking for someone to make an error.”

The following year, Rogers’s longtime friend Linda Rice Johnson, daughter of John Johnson, recruited her to become chief executive of Johnson Publishing Company. Rogers hadn’t worked in the industry before, but the family figured what she lacked in experience she made up for with marketing and leadership ability.

But it wasn’t an easy time for legacy print magazines, which never really recovered from the advertising drop-off after the Great Recession, when readers and advertisers fled to digital. By 2016, JPC sold Ebony and Jet to a private-equity firm, which resold them to former NBA player Junior Bridgeman in December 2020. (Ebony continues online.) At the time, Rogers said the magazines had been sold so the company could reduce its debt and focus on the growth of the cosmetics business. Rogers left JPC in 2017, and the next year, Fashion Fair faltered and disappeared from store shelves.

Rogers’s time at JPC left her intrigued by the possibilities of the cosmetics industry. In 2019, she and Mayberry McKissack teamed up and, backed by hedge-fund executive Alec Litowitz, bought the cosmetics line Black Opal. That same year, JPC went into bankruptcy; a few months later, the pair picked up Fashion Fair as part of the Chapter 7 liquidation for $1.85 million. “Fashion Fair is just too valuable for our community to lose,” Rogers told the Chicago Sun-Times. “We plan to modernize the brand and products but will remain true to the company’s roots, which was to create prestige products focused on women of color.”

Unlike when Fashion Fair launched in 1973, it’s reentering the market in what is arguably the golden age of Black beauty products. Fenty Beauty and its skin-tone and gender-inclusive products kick-started a major reckoning in the beauty world, while e-commerce and social media lowered the barriers to entry and success for independent Black cosmetics businesses like the Crayon Case and Beauty Bakerie. To modernize the brand, Rogers and McKissack brought on dermatologist Dr. Caroline Robinson to incorporate clean, innovative skin-care ingredients. The new line is vegan and fragrance free, to the dismay of many original fans who can still recall the cherry smell of their go-to lipstick. The packaging has been updated too, changed from the pink and, later, metallic-bronze shells to minimalist white with gold trim.

Former Fashion Fair makeup artist Sam Fine joined as the brand’s global makeup artist, overseeing the new line of products and shades. Fine’s goal is not only to add new shades but to meet the nuanced color needs of Fashion Fair’s customers. “Just because you tout 40 and 50 shades doesn’t mean you’re going to have my color,” he says, pointing out the wide range of undertones. The foundation sticks are more buildable and versatile for contouring and spot covering, and the company has added its first primer and four new nude lipstick shades alongside the ten original colors. There are plans to release new blushes, another erstwhile fan favorite.

Today’s Fashion Fair is also more mindful of inclusivity beyond race. “We have to make certain that we are open and that we realize this is a new day and time,” says Rogers.

While it benefits from nostalgia and name recognition, Fashion Fair still has a way to go to reclaim its former relevance. The company’s YouTube video count is currently six. Some of the older vloggers who were buying makeup when Fashion Fair 1.0 was around expressed disappointment that the relaunch wasn’t better publicized. Even some former Ebony Fashion Fair models and stans I spoke with hadn’t known the products were now available at Sephora.

Allana Smith, 45, of Brooklyn, discovered Fashion Fair cosmetics when she spotted the advertisements in her parents’ copies of Ebony and Jet growing up, and she began buying the makeup at Macy’s. All the counter artists knew her. One day, she went to Macy’s to re-up her Mocha Mocha foundation only to be told it was out of stock. “Then the weeks turned into months, the months turned into years,” she recalls.

Despite saving her products for special occasions and using cotton swabs to excavate drops of precious foundation from their bottles, Smith’s personal stock finally dried up while Fashion Fair was unavailable. Exasperated, she decided to give newer brands that touted a wide range of shades a shot. She settled on Fenty, and her usual backup is Flori Roberts, which she found on Amazon and considers the closest to Fashion Fair.

Now that Fashion Fair is back, she’s excited — but apprehensive. “It’s kind of like being in a relationship with someone, and you don’t want to have them get up and leave again and then you’ll be heartbroken again,” she says.

Rogers acknowledges that some customers have moved on to other brands in Fashion Fair’s absence. “Look, you can’t change history,” she says. “You know, you can say, ‘I wished, I hoped,’ but the history is what the history is.”

Instead, Rogers is looking to the future. This past fall, designer Anifa Mvuemba marked the tenth anniversary of her luxury womenswear brand, Hanifa, with a debut runway show at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Fashion Fair was the official makeup partner. “It’s full circle, right, in terms of how we’re thinking about the community,” says Rogers. “We’re just trying to stick to where we came from but freshen it up, you know? Take it to that next level, create this new microcosm of celebration for our wonderful Black designers and at the same time bring them the best that we have.”