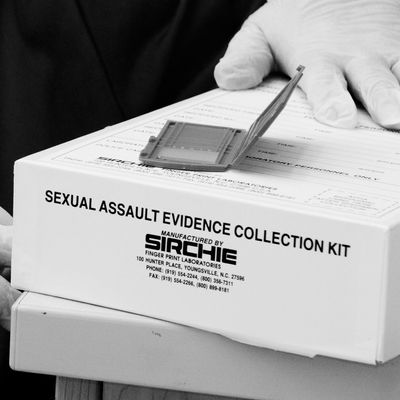

It recently came to light that the San Francisco police department may have used a database of sexual-assault survivors’ DNA to search for suspects in unrelated crimes, arresting a woman for a felony property offense after identifying her through her 2016 rape kit. The charges have since been dropped, but the woman is reportedly considering suing the city, filing a notice of a potential federal lawsuit on March 10.

“This is the ultimate betrayal and re-victimization at the hands of authorities and people that she sought help and protection from,” her attorney, Adante Pointer, said of the suit, according to the Associated Press.

On February 14, District Attorney Chesa Boudin said he had learned of the case the previous week: At the time, the San Francisco Chronicle reported, he could not say whether or not it aligned with police protocol or represented a one-off incident. But Boudin reportedly read the department’s lab to the Washington Post, which emphasized the word choice: “During a routine search of the SFPD Crime Lab Forensic Biology Unit Internal Quality Database, a match was detected and verified.” The head of that lab reportedly confirmed to Boudin that these types of searches occurred regularly. The DA told the Post the admission left him “horrified,” from both an ethical and a legal perspective.

“The primary concern that I and my office have … is with detecting and preventing future crime,” Boudin said, according to the Chronicle. “We want San Francisco to be as safe as possible, [and] we want survivors of sexual assault to feel comfortable and safe reporting and cooperating with law enforcement.”

It stands to reason that survivors would feel less safe bringing a rape or an assault to the police if they knew the DNA collected in a forensic exam — itself an invasive process that involves hours of extensive questioning, blood samples, and swabbing — might eventually be used against them. The underlying suggestion of suspicion could conceivably undercut the notion of comfort, too, particularly given that so many survivors already report uphill battles when it comes to getting law enforcement on their side. Then there is the California Victims Bill of Rights, which is supposed to protect the survivor’s privacy, at least in regard to their attacker. That law also states that survivors are to “be treated with fairness and respect for his or her privacy and dignity, and to be free from intimidation, harassment, and abuse, throughout the criminal or juvenile justice process.”

Speaking to the Post last month, Boudin also noted that the state constitution mandates that this kind of evidence should be destroyed or returned if it’s no longer being used to prosecute a sexual-assault or rape case. But across the country, huge backlogs of rape kits have piled up, many of them sitting untested for years. Boudin told the Chronicle that his office is trying to determine just how frequently police resort to this kind of evidence while investigating unrelated crimes, but said they had potentially accumulated thousands of survivors’ DNA over the course of “many, many years.”

In a statement from February, San Francisco Chief of Police William Scott said that, as far as he knew, “our existing DNA collection policies have been legally vetted and conform with state and national forensic standards.” Still, he acknowledged the matter was “sufficiently concerning” and said the department “will immediately begin reviewing our DNA collection practices and policies,” in cooperation with the city and district attorneys’ offices. Per the AP, Scott has since identified 11 cases in which rape kits in the crime victims’ database led to matches in other investigations. He also said that the woman planning to sue is the only person he knows of who wound up arrested.

This article has been updated.