On the first day they were eligible, I rushed my kids to get their vaccines. My husband and I have four kids: Jack, who is 10, 5-year-old twins, and a toddler. Our family knew that a COVID-19 infection in our household would threaten Jack’s life. Finally getting Jack and the twins vaccinated felt like a golden ticket. It meant that we could actually start creeping toward rejoining life.

Jack is a kid full of joy who loves drawing, swimming, and science. He was also born with cystic fibrosis, a genetic disease that causes thick, sticky mucus to build up in his lungs and digestive tract, leading to chronic infections. Each time Jack gets an infection, his lungs can be damaged, and their function deteriorates. When there’s scarring of his lung tissue, it is irreversible. Before COVID-19, Jack endured six hospitalizations, most of them for more than two weeks at a time.

To manage his disease, Jack takes six pills every time he eats, wears a vest that beats on the lobes of his lungs to help move mucus out, and uses nebulizers of three different medications multiple times a day. Simply put, Jack works harder for every breath he takes than any person you’re likely to have met.

COVID-19 is particularly dangerous for Jack because it could lead to permanent scarring of his lungs, permanent loss of lung function, a need for lung transplant, or even death. As Jack’s mother, my job is to make sure our choices give him the best chance at a full and long life. I fully understand the gravity of how each of my choices affect my son’s longevity. But during the pandemic, it’s not just my choices that affect his health, it’s also the choices of the people who are physically near him.

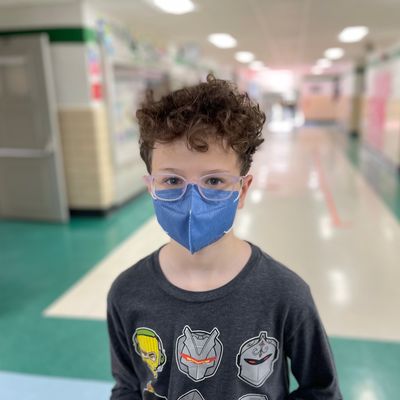

It seemed appropriate that November 3, 2021, was a sunny day because as we rode to the pharmacy in Haymarket Virginia, we were full of joy and relief. For the first time ever, my kids were excited to get a shot. They were strong as they got their injections and even smiled as I took a picture.

I told the kids we were going to celebrate by getting ice-cream cones to eat in the car. As the kids were chatting in the back seat, I turned a corner, and that’s when we saw it: A group of parents standing on the corner holding signs that read, “No Masks! No Vaccines! No Mandates!” They were chanting and yelling.

Jack was scared. He rolled up his window, and with a hitch in his voice said, “Mom, why don’t they want to keep kids like me safe?” My hope is that they have never met a kid like Jack and maybe just don’t know any better. But the truth is I don’t know.

Early in the pandemic we felt we must adopt the most extreme measures in order to keep our high-risk family safe. We pulled Jack from his second-grade class and our twins from their preschool immediately upon learning about Virginia’s first case. We adopted isolating and masking earlier than our community. We washed our groceries. Our children never left our house. When my husband had to go out, he changed clothes in the garage and immediately showered when he returned. We found fun things for the kids to do, like creating an ice-skating rink using dish soap on our kitchen floor. Because creating a “pod” wasn’t an option for us, our kids watched out the windows as the children on our street continued playing together. They missed their friends deeply.

Six months later, in the fall of 2020, school began again. Though Jack’s third-grade class would be learning from home, I hoped this would be a way to connect with his peers. But it was hard, made even harder by the fact that Jack has ADHD, which requires special education accommodations that are best provided in person. He struggled to focus and had a tough time navigating his assignments. Despite the fact that he had a fabulous teacher, there were many days that Jack’s frustration with virtual learning was so overwhelming he shut down entirely. I helped him the best I could, but I am not a trained educator. We all struggled.

Our school district transitioned to hybrid learning during the second semester of third grade. We were ecstatic. After consulting with Jack’s physician team at Johns Hopkins we made the decision to send Jack back into the classroom two days a week. Even though Jack is high risk, the layered mitigation strategies, like universal masking and strict social distancing, put in place at his school combined with a period of low transmission rates made going into the classroom possible for him. While hybrid schooling came with its own set of challenges, Jack was excited about school. He kept up with his assignments and engaged with his class.

But last fall, Jack began experiencing a “CF exacerbation.” His lungs were inflamed, he was coughing, and he needed medical care. When the first positive case of COVID-19 showed up at our school there was still no vaccine available in his age group. His lungs were compromised and he had to be switched to homebound schooling, a service provided to children during times of hospitalization or high medical-care needs. A special-education teacher travels to your home or hospital room for an hour a day to provide you lessons in hopes you can keep up with the rest of your class until you are able to return. It’s not designed to be a long-term equitable education resource.

This type of learning was very hard for Jack. He felt rushed, stressed, and inferior to his peers. After he received his second vaccine he was finally able to return to his classroom. Jack was learning in person full time and thriving. We saw a child blooming before our very eyes.

One short month later, on January 15, 2022, Virginia’s recently elected Republican governor Glenn Youngkin signed an executive order effectively banning mask mandates in school. When we heard the announcement on the radio in our car my heart sank and my mind raced. Did Jack hear it? I glanced to my right and there he was, looking at me with a question on his face and tears welled up in his eyes: “Does that mean I can’t go to school anymore?” He knew as well as I did that if universal masking at school went away, he would no longer be able to go. Jack has the same right to access his education as every other kid at school. His education should not suffer because he happened to be born with a disease. I reached out to the disability community to find help quickly.

Last week, I filed a federal lawsuit alongside 11 other families challenging Youngkin’s executive order. We asserted that it violates our children’s rights under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Rehabilitation Act (Section 504). Other states, including New Jersey, Connecticut, Delaware, and Oregon have announced plans to lift masking requirements in schools, but wouldn’t do so until March. Youngkin wants to make it possible for parents to opt out of masks immediately.

The order has been temporarily halted from going into effect pending legal action in seven school districts, but we don’t live in those districts and don’t know what will happen in ours. There’s also a bill making its way through the state legislature that unilaterally gives parents elective choice in masking their children at school. This sends a clear message to all families like mine: We aren’t being considered when these orders and laws are being written.

Are we asking for every school to universally mask in perpetuity? No. But each school needs to have the flexibility to reasonably accommodate the students with disabilities at their facility. What that looks like for one school may be different from another. Schools need to be able to look at local data and recommendations from the doctors of their students and implement the required mitigation strategies that will keep the most vulnerable children at their school safe and able to attend classes in person.

In Jack’s school, he needs universal masking indoors during periods of moderate to high transmission of COVID-19. There are other students whose disabilities may preclude them from being able to wear a mask at all; they need the children around them to be masked for their safety. The plain fact is that Jack and all children with disabilities are entitled to equal access to a public education. It is their schools’ responsibility to ensure there are no barriers preventing them from attending school. The governor cannot stand in the way.

I understand that there are many parents who don’t want their kids to wear masks at school because it’s inconvenient or uncomfortable. They believe masks should be a personal choice. But for children like mine, when their peers take their masks off, they make it impossible for kids like Jack to walk in the front door of their school. Jack and kids like him don’t have an equal personal choice — they must follow their doctors’ recommendations, and right now those recommendations include their peers masking. My son should not be told he must be willing to die to go to school. At its heart that is the horrible truth of the great mask debate.