During my Gen-X childhood it was totally normal for my friends’ parents to smoke cigarettes while driving a car full of kids home from swim team or soccer practice. Today, especially in my white, middle-class social circles, that would be a scandal, albeit an incredibly boring and judgy one.

Now, can you imagine if it was weed?

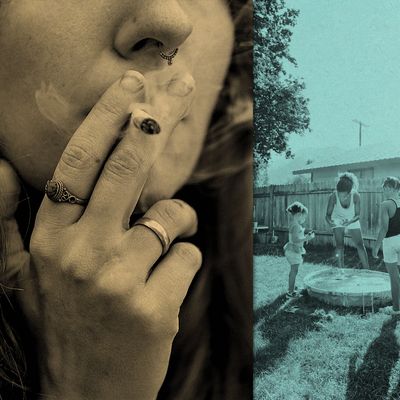

Most of the parents I know are happy to take a gummy to help with sleep or occasionally smoke a bowl or joint for fun and relaxation. But only if no children are present. At a barbecue at my house last summer, a friend discreetly handed out small Mason jars full of homegrown cannabis (mellow and relaxing, with giggly undertones), excess from a backyard experiment that left him with far more than he could use himself. The other parents thanked him; secured their stashes in their canvas totes, glove compartments, and cargo shorts; and continued to sip on their IPAs and margaritas. Cannabis is perfectly legal in Vermont, where we live, so if we wanted to sample it, we could have. No one dared suggest it, myself included.

The reason: the kids bouncing on the trampoline and running through the sprinkler. Instead, we kept downing our for some reason much more socially acceptable alcoholic beverages.

In the 18 states (plus the District of Columbia) where cannabis has been fully okayed for recreational use, consuming it is legally no different than drinking a glass of wine. Culturally, though, we’re still working out what casual, legal marijuana use looks like, especially when it comes to how we use it around our children. Popping a gummy after the kids go to bed? Almost no one is going to raise an eyebrow at that. Smoking a joint at a family barbecue? Depending on your social circle, that might get you uninvited from the next one.

As we move closer to what now seems like the inevitable legalization of marijuana on the federal level, or at the very least full legalization in most states, the social rules around cannabis are also bound to evolve. Specific laws governing cannabis possession and use vary by state, but parents can be charged with child neglect or endangerment if substance use puts children at risk of harm.

The problem with this, of course, is that harm is subjective — what a parent might consider equivalent to consuming a glass of wine, or taking a medication for high blood pressure or chronic pain, might be seen as drug use through more conservative eyes. In New York State, parents and guardians cannot be accused of neglect or abuse simply for using cannabis. However, legal marijuana use, even medical use, has often been held against families involved in the child-welfare system, especially Black and brown parents, and families living in poverty seeking government assistance.

And then there’s the casual shade. “Some parents who are not pot smokers would give me a hard time that there was still pot in my house,” Alix, a Bay Area mom who asked that I only identify her by her first name to protect her family’s privacy, tells me. “And this is like, we were getting toward the point where at least medical marijuana was being decriminalized.”

Jamilah Mapp describes this sort of side-eye over cannabis use as part of the general bullshit of parenting comparisons, no different than shaming other moms for relying on screen time or allowing soda. “If you’re not ready for your kids to see Mommy smoke a joint, then don’t bring them over to my house,” she says. “Stop judging each other; whatever the fuck you do over there is great. And whatever I’m doing over here is favorable.”

Speaking openly about subjects that are often seen as off-limits, like sex, money, and cannabis, is part of Mapp’s identity. She lives in Southern California and legally and openly enjoys cannabis around her 6-year-old daughter in a way that is different from, and also rooted in, the way she grew up. “Both of us came from families that smoked weed but hid it,” she explains, referring to Erica Dickerson, her co-host on the podcast Good Moms, Bad Choices. “I’m normalizing it and not making it a secret for my kids, just like any mom would pour a glass of wine in front of their kid.”

Alcohol isn’t just accepted in parenting culture, it’s ubiquitous, and, in the case of the “wine mom,” even celebrated — not that this is necessarily a good thing. There’s a paradox here, a deep kind of weed hypocrisy that I admit to perpetuating. Personally, I believe cannabis to be less harmful to the human body and spirit than alcohol, and I believe it can be therapeutic, for sleep, for anxiety, for pain, in a way that alcohol just isn’t. And yet I’m far more comfortable drinking a glass of wine in front of my kids than vaping or taking a gummy. I blame Nancy Reagan — it’s vestigial stigma left over from just saying no.

“We grew up in the DARE era, when drugs were this very bad thing but drinking was socially acceptable because it’s legal,” Emily Farris, writer and host of the podcast Mother Mother and self-identified “geriatric millennial,” tells me. Farris, who lives in Kansas City, Missouri, where marijuana has been decriminalized, uses it as a medically prescribed sleep aid and tells me she treats it like any other medicine. “I use the term ‘THC’ in front of the kids,” she explains. (Her sons are 6 and 2.) ”I don’t use fake terms for genitals, so I feel like when it comes to other things that society finds taboo, the more I can be scientific and straightforward about it, the better.”

Farris echoed my cannabis paradox. She writes about and develops cocktail recipes, and her husband works at a brewery. She’s comfortable drinking in front of her children, and while she’s open about the fact that cannabis exists and that it’s something adults enjoy, it’s not something anyone openly does in her home when the kids are present. “Which is so weird because I know that there have been times that alcohol has turned me into a monster,” she says. “Weed turns me into the Cookie Monster, but that’s about as bad as it gets.”

As she is quick to point out, for white moms, like Farris and me, frank discussion and use of cannabis is evidence of a certain kind of privilege. Marijuana use is often stigmatized, especially for brown and Black parents, even in states where it is legal. Mapp says that whether it’s cannabis or talking openly about sex as a podcaster, there’s always an extra layer of complexity for Black women. “Things that white moms do and get away with and it’s funny and quirky and hahaha, people are a little bit more judgmental,” she says.

When I ask other parents to share their current cannabis philosophies with me, a few nearly universal concerns emerge, some of them grounded in lessons we’ve learned as a society since my ’80s childhood. Driving while high is dangerous. Secondhand smoke is not good for young lungs. Edibles that look like candy need to be handled with care. Getting so high you can’t form a coherent sentence is not compatible with parenting — though almost every parent I chat with mentions that Legos, blocks, Barbies, and fingerpainting are all improved by being a little high.

The topic that inspires the most worry, though, and which seems far more intractable than the others, is teenagers and cannabis.

Nicole Eisenberg and Marina Epstein, two researchers at the University of Washington who have studied how the legalization of marijuana affects parenting, say that in their work they have found that many of the parents they talk to, many of whom enjoy cannabis themselves, want help talking to their children about it.

When I ask them whether modeling responsible cannabis consumption could be helpful, they dismantle one of my long-held beliefs, one I know many of my parent friends also hold: Americans binge drink because we lack a healthy drinking culture compared to Europeans, and parents who enjoy a moderate glass of wine with dinner are showing their children what drinking should look like. Research does not bear this out. According to Eisenberg and Epstein, not only do Europeans and Australians have very high rates of binge drinking and alcohol abuse, children who are exposed to substances, including alcohol and cannabis, at an early age are more likely to abuse those substances later.

“It’s called the harm-reduction model, this idea that if you just introduce alcohol to kids in a non-hyped way, not a forbidden-apple way, you show them that you can have one beer or one glass of wine with dinner, then that is going to turn them into responsible drinkers,” Epstein explains. “It turns out that introducing kids to alcohol at a young age is a terrible idea. Because all you’re actually doing is introducing an addictive substance. It’s not the same thing as teaching them how to drive or how to save money or spend money responsibly.”

It isn’t so much that modeling moderate use is bad, Eisenberg clarifies, as that a laissez-faire approach comes with the risk of early exposure and can take the place of strategies that have been shown to reduce marijuana use by teens — like minimum age requirements, clear labeling, and lockboxes in the home for cannabis products. Transparent communication around cannabis laws and boundaries at home are crucial, she says: “Marijuana might be legal and okay for adults, but it’s definitely not okay for young kids or for developing brains.”

To date, there has not been good data showing how cannabis use affects adolescent brains, and there are no nuanced studies that could provide guidelines indicating how the age of the user, the amount of THC, and how it’s delivered might lead to different outcomes. (Science agrees that smoking marijuana is bad for lungs, but not on whether it causes lung cancer, like tobacco.) Eisenberg and Epstein are clear that their work focuses on attitudes and behaviors around cannabis use — they don’t have an MRI machine in their lab and don’t track changes to brain anatomy. “The bottom line seems to be that the most deleterious effects are of early and consistent use by young people,” Eisenberg says. “That is where you get … effects on cognitive functioning, school achievement, there’s some links to mental health.”

Alix tells me that her sons, who are now almost 18 and 20, had never seen her use cannabis until very recently, when she shared a joint with them at a concert. “It’s only within the last year that they have seen me smoke pot,” she says. “And that’s because they’re adults.”

Adolescent brain development was top of mind for Alix as she was feeling her way through parenting two teenagers. On a family trip to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, she was struck by an exhibit on brains that highlighted the way that neural pathways are formed and how repeated behavior, or substance use, can shape the brain. “These pathways that you develop at adolescence can really get burned in really deep, deep grooves,” she says. “I didn’t want my kids’ pathways to be so deeply grouped in alcohol and marijuana.” Epstein and Eisenberg also pointed to early, regular, and heavy marijuana use as being the most problematic pattern for adolescents.

Alix, who has been consuming cannabis fairly regularly since college, made sure that her children did not see their parents smoking pot, while keeping open the lines of communication and speaking frankly about her and her husband’s experiences with it, both good and bad, something Mapp also identifies as important. “The first time I smoked weed was with a bunch of, like, 12-year-olds, and they were giving me education on shit they didn’t know anything about — same with sex,” Mapp tells me. “Because we don’t feel comfortable talking about sex with our parents, we’re getting sex advice from teenagers. That’s crazy.” She and Dickerson are so committed to helping modern parents talk about cannabis in a smarter way than our parents did that they recorded a whole show about it.

My kids are just barely in elementary school, so I have some years still to establish an ongoing conversation around cannabis (and I’m really thinking about how I want to consume my old frenemy alcohol in front of them). My husband and I tend to be more frank with our kids than average. Just as Farris doesn’t use made-up, cutesy words for marijuana or human anatomy, we try to explain simply, but honestly and clearly, any questions our children pose to us, whether they’re about racism, Ukraine, or our friends who, through a complicated mix of open adoption, divorce, and re-partnering, have four moms and two dads, all with very different roles.

My son has registered the idea that smoking cigarettes is bad, and while I’m wary of some of the class-based implications around that, nicotine is so addictive, and tobacco companies are so unscrupulous, that I’m comfortable with a blunter than usual conversation as far as that goes. Neither my husband nor I have even been passionate cannabis users in any format, so I’ve been trying to hone our conversation around alcohol, which is regularly consumed in our house, to be the scaffolding for talking about pot. When my kids ask to taste my glass of wine, I tell them it’s for adults only because our bodies are different — their brains are growing very quickly, and alcohol can affect that. I say that grownups aren’t just kids with bigger bodies, that we have different abilities to deal with things that might be enjoyable or useful, like wine or driving, but are also risky. And I tell them that my biggest job is to keep them safe and that alcohol use isn’t safe for them, and that when they are adults they can make their own decisions about it. But not until then.

And when they are teenagers? “Having clear guidelines, monitoring behavior, and having consistent and moderate consequences can also be useful in preventing problematic substance use,” Eisenberg wrote in an email.

I also want my children to understand that whether it’s a Manhattan or a bong hit, healthy use of any substance requires honesty about why you’re using it. I really enjoy my coffee in the morning, but I’m also clear that I’m dependent on it, which, at this point in my life, is fine by me. I worry that today’s cannabis is both far more powerful than the dusty baggies of ditch weed I smoked in high school and a little too efficient, making it impossible to ignore the core truth: We use cannabis to feel different. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it does beg self-examination.

I’m cognizant of Eisenberg and Epstein’s warning about casual use turning into early exposure and access, but I’m equally aware that in every other aspect of my parenting, I’m offering my children a clearer window into adult behavior than the one I grew up with. And I’m not the only one. “When I was a kid, it seemed like they were insulting my intelligence when they would come back from the garage smelling specific and not saying anything,” Mapp tells me. “And I just encourage moms especially to reparent themselves and reconsider the things that we’ve inherited.” Because, as she points out, “Was that even productive?”