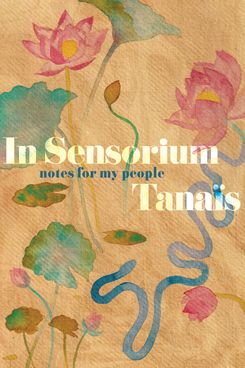

Scents, as ephemeral as they may be, are a type of knowledge system: When we smell something, it relays information to our neurons that triggers feelings, thoughts, and memories. “Whereas the body cannot escape circumstance … a perfume allows us to, if only for a moment,” writer, artist, and perfumer Tanäis writes in their newly released memoir In Sensorium: Notes for My People.

Through a series of investigations into the origin and capture of notable scents throughout history, In Sensorium takes us through the ambitious project of mapping scents to Tanäis’s own history and the histories and connections that come from their own embodied experience as an American Bangladeshi Muslim femme.

Can tracing scent give us a mapping to our most authentic self? Can it conjure longing and desire? Can it connect people across differences? Tanäis and I connected on a dance floor in the Lower East Side. We had actually met once before, but as they write, “Sometimes powerful femme energy intimidates, and you want to run from what arises in its presence.” That night, we didn’t run. Instead, we talked late into the night about where our experiences were shared and where they were fractured.

So when their new book came out, I knew I had to talk to them about their new project.

Let’s start at the beginning — I love the idea of scent as a way into storytelling.

I think we have this map that we’re creating of the world if we have sight, but our sense of smell is not one that we’re necessarily attuned with. So much of the sensory worlds that I explore in the book are coming from other olfactory milieus.

The South Asian scent scapes that I draw from as a perfumer and as a writer are things that are inhabiting my body and mark my body, but are not necessarily things that I grew up with in the places that I’ve lived. So I talk about my grandmother and my mother’s perfume, altars at our house growing up in these small apartments that would envelop me in this sensory identity separate from what I was growing up in, in the Midwest and in New York.

So when did you become a perfumer?

I really made my first foray into perfuming in 2014, starting with all-natural materials. I took a perfumery class with Indie Perfumer and I made a very unsuccessful perfume, but I was like, “This feels like another mode of expression and building an art object that is using disparate materials, disconnected materials.” As a perfumer, there’s a huge palette of aroma chemicals, and it’s sort of like where the synthetic and the natural meet is something hybrid that I really found to be more compelling. So I have been doing it for eight years, and as I’ve gone deeper into the practice of perfumery as a self-taught perfumer, I’ve found a huge range of olfactory materials to work with.

Has becoming a perfumer been a type of reclamation for you?

Absolutely. One of the things that you learn as you try to decolonize yourself is that you speak in a language that is not necessarily your mother tongue. You hold yourself and carry yourself and dress yourself and adorn yourself in clothes that are of the culture in which you are living, but then there are all these other modes of adornment that also belong to us. Reaching that place through smell and using materials that are very rarely used in western palettes — like the scent of Mati, using clay from the Ganges River steeped in sandalwood, turmeric, tobacco, things that are very strong and just this idea of a body being smelly and being ripe — it all influences how I want to reclaim and wrest back materials that were stolen and adorn them on our bodies.

In the book, you address the experience of being South Asian in the United States, but also push away the idea of this unified sense of being South Asian. Can you talk a little more about that?

Part of the narrative we need to deepen in our understanding of South Asian [identity] is knowing how acknowledging difference has really been a part of undoing domination and the way that you have a system of caste that divides people between those who are considered pure and those who are polluted. It’s a very violent system, and to reject that naming as other, or as unworthy, is very radical and I think that’s the place where I kept trying to go. I think what’s happening today with India and the rise of violent fascist forces trying to suppress the expression of Muslim culture and Muslim people’s livelihood and freedom is the continuation of something that was really calcified during colonization by the British, which is the separation of all of us by caste and religion as permanent divisions between all of us.

And I don’t believe anything is permanent.

Even Isabel Wilkerson’s groundbreaking book Caste, which looks at how racism is also a type of hierarchical system like caste, doesn’t address the ways that caste has actually been imported into the United States and reproduced in both minute and larger ways within the South Asian American community.

Absolutely. And now that we have people in the U.S. context, fighting caste discrimination, whether it’s in a university or a tech company, it’s very powerful because then that kind of veil that we have, that we are all brown people, we’re all the same, it sort of disintegrates. Because there are people of color who benefit from allegiance to whiteness and power and that is something that we need to unpack now, as we become more conscious and move towards liberation.

Tanäis and Samhita Mukhopadhyay will be in conversation at the Brooklyn Museum on March 10. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.