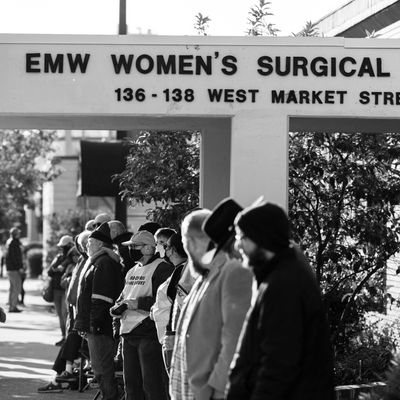

Kentucky lawmakers effectively ended abortion throughout the state earlier this week, overriding their governor’s veto to enact a singularly aggressive omnibus ban. The legislation, known as House Bill 3, outlaws abortion after 15 weeks. It also includes a tangle of wild extras that the state’s two remaining clinics — a Planned Parenthood and the EMW Women’s Surgical Center, both located in Louisville — say make it untenable for them to continue abortion services, at least for now. The state house and senate, both controlled by Republican supermajorities, voted 68-21 and 31-6 to push the measure through on Wednesday night, meaning that Kentuckians with upcoming abortions scheduled saw their plans disintegrate by Thursday morning.

“People who had appointments at the clinic have had calls from their provider to let them know that they can’t receive care,” says Meg Sasse Stern, director of the Kentucky Health Justice Network’s abortion-support fund. KHJN is now doing damage control, trying to help panicked patients reroute their plans on an ever-tightening timeline. “Our callers are highly aware that they’re working against the clock with pregnancy care,” Stern adds. KHJN expected HB 3’s passage and prepared for it, but nonetheless, Stern says the fund now finds itself in “crisis mode.”

The terms of the law are shocking in their volume, as if lawmakers simply threw “the entire pot of spaghetti at the wall,” Stern says, rather than going “one piece at a time.” The 15-week provision mirrors the Mississippi law currently under consideration by the Supreme Court, in that it makes no exception for rape or incest. If Kentucky lawmakers had stopped there, HB 3 wouldn’t be groundbreaking — conservative states are scrambling to enact new restrictions, anticipating sweeping revisions to Roe v. Wade when the Court rules this summer. But instead, Kentucky legislators piled on provisions that (among other things) obligate providers to register through a special system that doesn’t actually exist in order to offer medication abortion services. The law requires providers to report each abortion they perform to the state, handing over biographical details on their patients — such as information on previous pregnancies and even STI histories — if they want to keep their medical licenses. The finished product reads like a supercut of the anti-abortion movement’s most extreme legal hits, and while Planned Parenthood and the ACLU have sued to block the law, it’s not immediately clear if they’ll succeed. For now, the combined weight of so many regulations has plunged Kentucky’s patients into confusion and its abortion funds into overdrive.

Abortion funds exist to help patients cover not only the cost of the procedure, but also the fees that barriers to access add to the bill. “Before the ban hit, abortions in Kentucky cost between $700 and $2,050,” Stern says, and “the more care is delayed, the more costly it becomes.” Dwindling clinic numbers obligate patients to travel longer distances, and often over state lines, to obtain an abortion. Waiting periods — which range between 24 and 72 hours, depending on the state — may mean paying for accommodations and meals in between appointments. Most patients already have at least one kid, and may have to account for child care during the process. Having to take time off work means that many will also lose wages while their tab grows.

Each person who contacts KHJN is paired with a case manager who assesses their particular needs and goes over the available resources: money for gas, hotel stays, food, transportation to and from the appointment, occasionally even airfare. For the time being, Kentucky patients looking to end their pregnancies must cross state lines to do it: Those close to Louisville, for example, may look to a clinic across the river, in New Albany, Indiana. Other residents may look toward Cincinnati, Ohio; or Virginia; or Illinois; or Tennessee. KHJN typically is able to contribute between $100 and $200 per caller, but Stern says that after an especially busy January and February, the organization has already allocated $70,000 — “a massive chunk of our operating budget.” Now that Kentucky’s clinics have suspended abortion services, staffers and volunteers have been working overtime.

“The callers need support when they need support,” Stern explains. “They have their own lives and their own situations going on; we’re often talking to people while they’re taking care of their families or texting with them on a work break and catching up later in the evenings.” In a moment when patients find their plans upended, when they must once again reconfigure their schedules and finances while the clock ticks down, Stern says she and her colleagues are trying to mitigate callers’ confusion even after their shifts end. For her, “There aren’t really going to be off hours.”

Providers everywhere have felt the squeeze as conservatives, who anticipate that the Supreme Court will substantially revise or overturn Roe, have escalated their crackdown on abortion. Scarcity in just one state can bleed out across whole regions: After Texas outlawed abortion services past six weeks of pregnancy, residents made appointments in neighboring states and even across the country. In nearby Oklahoma, the wait time for an appointment reportedly extended from two to three days to three to four weeks. Those delays may have prompted Oklahomans to look elsewhere for abortion services, even before the state’s governor signed a near-total ban on the procedure. Multiplying restrictions compound overflow, which in turn increases the strain on abortion funds: The longer a person has to wait to terminate a pregnancy, and the further they have to travel to do it, the more expensive the entire thing becomes.

Stern emphasizes that patients in the Bluegrass State still have options: “Kentuckians can, and always will, continue to have abortions.” But if Roe falls, many of the states that border Kentucky — Indiana, Ohio, West Virginia, Tennessee, Missouri — will likely ban the procedure as quickly as possible. To even attempt to meet the ballooning needs of a post-Roe landscape, abortion funds will need donations like never before.