This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

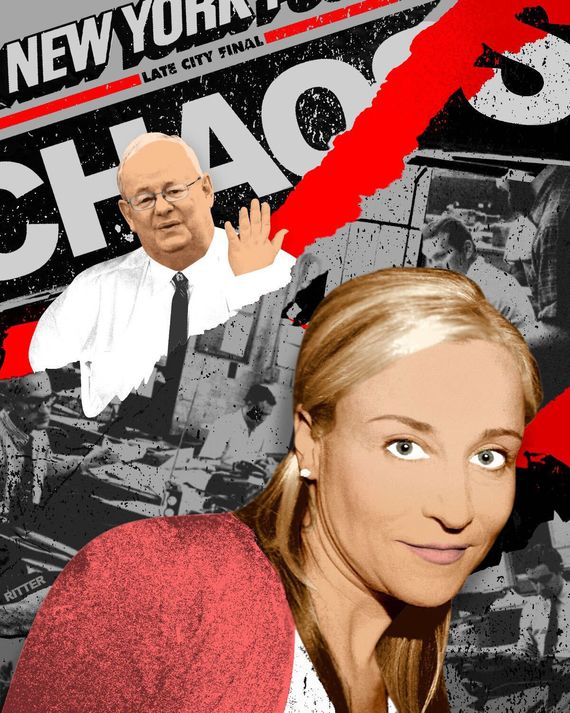

Michelle Gotthelf’s final day at the New York Post started like any other: an hour-long commute from New Jersey to the newspaper’s largely empty Midtown high-rise; settling into the office she’d gussied up with bubblegum-pink walls, a unicorn mural, and a glass chandelier. Then, a Slack message from her boss: Could she come to HR immediately? As editor-in-chief of the Post’s digital operation, Gotthelf wondered if she would get pulled into an investigation or find out the paper had been hit with a lawsuit. Maybe someone had died. Instead, an HR manager told her the company wouldn’t be renewing her contract.

Shocked, she asked, “Is that your final decision?,” looking over at Keith Poole, who had recently been hired to run the Post. “Afraid so,” he said, then swiftly left the office.

By the time Gotthelf returned to the newsroom floor, her work badge had already been deactivated. After more than two decades at the company — this happened in mid-January — she suddenly had to wait “like a thief” to follow someone else inside. She sat in her office chair stunned before shoving a gray cashmere sweater in her purse and fleeing the building. This is retaliation, she thought. She had devoted her career to creating what she describes as “the most competitive newsroom in the country” without so much as a bad performance review. How dare they treat her this way?

But when she filed a lawsuit a few days later alleging she was axed for telling Poole that she had been sexually harassed by Col Allan, the Post’s former head honcho, the reactions were divided. Depending on whom you ask, Gotthelf was either a strong female leader in a misogynistic shark tank or a perpetuator of a toxic newsroom culture. “The way the Post is run can be really summarized by misogyny and control,” says one former reporter who left in the past few years. “The only way they get all these very talented reporters to work for them is by making them feel like fucking shit. When you make someone feel like shit, they constantly try to impress you.” Many Posties, current and former, told me Gotthelf was at times the one who made them feel that way.

Shortly after she filed her suit, Gotthelf released a statement saying she hoped it would lead to a “positive change for other women at the Post.” While some wished her “a big fucking settlement,” others scoffed at any suggestion that she was the paper’s feminist savior. “Michelle held on to this so that she could wield this dirt, weaponize it, when it suited her,” said Laura, a former editor who, like many sources for this story, asked to go by a pseudonym, most of them fearing career backlash.

The Post calls Gotthelf’s description of the meeting on her last day “inaccurate” and says Poole told her exactly why her contract wasn’t being renewed; in a legal filing, the company says she created “disunity” in the newsroom, denying that she was fired or the victim of gender discrimination. They also reject any allegations that the company dismissed or punished Gotthelf for expressing concerns about Allan. For his part, the former editor-in-chief claims he never harassed or propositioned Gotthelf for sex. “He supported her career at the New York Post and promoted her there,” says his lawyer.

None of the other Posties I interviewed doubted her claims — there has been widespread reporting of crude behavior by Allan, who retired in 2016 before being brought back in an “advisory role” ahead of the 2020 election — but some still had trouble seeing Gotthelf as a blameless victim given her influence over the newsroom. In more than 40 interviews, current and former Posties described a place where, over the past few years, management has been able to yell, slam phones, and demean reporters without getting so much as a slap on the wrist from HR. While there are safe pockets — “I’ve never been called names or harassed. I’ve never felt preyed upon or physically uncomfortable,” says one reporter who doesn’t cover news — others say sections like the Sunday paper and the metro desk have been run by an old guard who confuse dictatorship with leadership. Rather than breaking this cycle — perhaps a lofty expectation for the only woman at the top — Gotthelf, some Posties say, greased its wheels. “Michelle is like the horribly abused child that goes on to abuse others,” says Laura.

The Post says it does not tolerate bullying or misogyny and that any such accusations do not reflect “current conditions.” A spokesperson noted that the newsroom has been remote for much of the pandemic and pointed to the fact that women are now in charge of multiple departments.

Many of Gotthelf’s defenders see the Post’s hard-knocks environment as the secret sauce that fuels its brazen journalism. “It’s part of this orchestra,” former managing editor Joe Kemp, who is 42, says of all the shouting and swearing in the newsroom. “Everyone has their part in the symphony.” Hailey, a former reporter, went in knowing she wouldn’t be treated like “an intern at The New Yorker.” The paper tends to breed loyalty among self-described media underdogs who don’t need Ivy League degrees to scoop their snooty competitors. “That shark tank is not for every minnow,” she says. “If you wonder what it’s like to work at the New York Post, read the fucking pages of the New York Post.”

Gotthelf has always been drawn to the idea of stripping the news down to its most essential parts. “I love the sizzle of a tabloid,” she says over Zoom one February afternoon from her home in New Jersey. “I love being able to tell stories in the least boring way.” The 49-year-old has pin-straight blonde hair, wears oversize black glasses, and talks at a quick clip, always ready to answer my question before I’ve spit it out.

After graduating from Long Island’s Hofstra University, Gotthelf covered crime for a New Jersey newspaper and an online news service. Making sure the public knew these stories and helping families grieve gave her a sense of purpose. “It really set me up for my entire career,” she said on a recent podcast. “I don’t want to say it’s a life calling, but it’s a part of me.” In 2000, when she was in her late 20s, she was hired as a Post reporter and took to the job like “a fish to water,” electrified by the tabloid that had been the whiskey shot of the news world ever since Rupert Murdoch bought it in the mid-1970s.

With its cheeky headlines and punny ledes, the paper gave every local story the feeling of a sensational scoop. (“Holy Cow!” begins a recent article about stolen steaks, which spun a few shoplifting incidents into an epidemic of “money-making thieves” worthy of multiday coverage.) While the newspaper also runs investigative reporting, often written by left-leaning staffers, its editorial view still boils down to good cops and bad robbers. But even New Yorkers who loathe its politics can’t help but guffaw at the crude-but-clever, New York–style clapbacks on the Post’s front pages, known as “the wood” (“Best Smacktor,” read the headline the morning after the Will Smith–Chris Rock Oscars debacle), and its reporting on gritty local crime, scandals, and political kerfuffles is often unrivaled.

In the ’80s, the Post was the kind of place where “people came into the office hung over, they slept in the darkroom, reeking of liquor, kick-me signs hanging on the backs of chairs,” a former Post photographer told the author of the book America’s Last Great Newspaper War. In the aughts, it was still full of “zany alcoholics shooting out stories” who considered themselves a “band of rebels,” according to a former staffer. There was less debauchery by the time Gotthelf joined, but motivation by fear was still the norm.

Around that time, Allan, a temperamental, foulmouthed Australian transplant, and a friend of Murdoch’s, was put in charge of the newsroom. Allan seemed to fancy himself the leader of a swashbuckling pirate ship full of outlaws; he was best known for pissing in his office sink when he was editor-in-chief of the Telegraph, launching into booze-soaked tirades from a barstool at the Post’s old watering hole, Langan’s, and having brought high-profile politicians to the New York strip club Scores. Most reported anecdotes about Allan read like Hollywood caricatures of a monstrous boss stuck on yell mode, like the one about the time he cracked his own cuff link after slamming his desk while ripping into an underling, or the time he fired someone via voice-mail while drunk only to forget the next day. Luis Rendon, a former senior designer at the Post, remembers being scolded by Allan in 2019 for talking too loudly in an adjacent office. When Rendon later tried to apologize, Allan pointed at him and said, “Get the fuck out of here. I don’t want to see you again.”

A few months after he took over, Allan cleaned house, but Gotthelf made the cut, receiving a series of title bumps that landed her the deputy editorship of the metro desk by 2004. Climbing the ranks meant she got to see the Post’s frat-party ethos under even brighter lights. She says she was initially passed over for one promotion because Allan wanted a “strong man in the job.” That man was also “substantially less-qualified” and had “no experience running a newsroom,” according to her lawsuit.

Well into the aughts, the Post was still running the kind of operation where certain male editors might touch your “boob or butt,” according to Meredith, a former reporter. One lawsuit, filed by a former Postie a decade before Gotthelf’s complaint, alleged that David Boyle, a former photo editor, was known for “bumping” and “grinding” with the 20-something female assistants whom it said he referred to as “David’s Harem” at holiday parties. (A spokesperson for the Post at the time called the lawsuit baseless; the case was later settled.)

Still, in many ways, the Post remained a hungry reporter’s dream. It’s one of the last bastions of shoe-leather local coverage, where staffers are sent on last-minute stakeouts or to hang out at police headquarters until officers know them by name. “It was the most fun I’ve ever had by far,” says Meredith. “It’s like you’re this piece of New York City,” says another former reporter. There’s a strong camaraderie that comes from being thrown into intense situations together, and Posties wear their toughness like a badge of honor. Gotthelf boasted in a recent interview that “we’re still old-school journalists here.”

By 2007, she had become the first woman in the Post’s history to lead the metro section, which meant she oversaw a staff of some 60 reporters and got her own office. She relished making the men “a little uncomfortable” with her over-the-top décor. “No glass ceiling here! #Girlpower!!!!” she captioned a photo posted to Instagram of her office, with a bright-pink boa and a crown-framed mirror on the wall. “I was having fun, for fuck’s sake,” she says.

Even as the Post began opening its upper ranks to white women like Gotthelf, entry into the boys’ club remained largely out of reach for her colleagues of color. “As a Black woman, there weren’t a lot of us,” says Emily, a former reporter who left the Post in 2014. “I was not given the opportunity to be fast-tracked into higher levels like other people were.” (A 2010 lawsuit that was later settled alleged that a Black woman of Puerto Rican descent was fired for complaining about a racist cartoon of Barack Obama that ran in the paper.)

But the management world turned out to be a “hostile work environment,” says Gotthelf, where Allan allegedly called women names like “skank,” “stupid,” or “sneaky lesbian” and told her that Murdoch “doesn’t like many women.” She says as his marriage dissolved, Allan turned his vitriol directly on her, asking “Who do you think you are, my wife?” in newsroom debates, an allegation he disputes. She says her male boss at the time shrugged off her complaints with “Not much I can do.”

In 2015, Gotthelf claims, the harassment peaked. At a work dinner with other editors, she says, Allan “made a point to be physically close” and was “hovering over her.” The complaint says he then asked her to join him for a drink afterward and, once they were alone, turned the topic to sex. “We should sleep together,” he allegedly said, after asking about her sex life and divulging details about his own. When she rebuked him, she says, Allan added that he had slept with another colleague. “Stunned, Ms. Gotthelf left the bar and grabbed the first taxi she could find to get away,” says the lawsuit. (Allan denies acting inappropriately or saying he had slept with another Post employee.) She didn’t immediately report him to HR because she feared retaliation. But as Allan became more aggressive, ripping up a list of her story ideas and telling her to “get the fuck out” of a meeting, she says, Gotthelf made an official complaint.

Hailey, who worked at the Post during this time period, described Gotthelf as a buffer who “somehow grinned and beared” Allan’s tirades. “She ate that shit for breakfast every single day,” says the former reporter. “It’s amazing, I’ve never seen her cry.” Even while absorbing Allan’s anger and alleged harassment, Gotthelf says she tried her best to shield reporters from his wrath and female staffers from “unchecked men” in general. “I had a big mouth,” she says. “If I see people mistreated, I’m going to HR; I’m going to our lawyers.” Hailey likened Gotthelf to “the head sister at the sorority,” and said she was a mentor who helped her land front-page stories: “I was her golden goose. She took care of me.” One woman still at the Post says that Gotthelf protected her “from a lot of the bullshit” doled out by powerful men at News Corp. and encouraged her to file HR complaints against male bullies. Another says Gotthelf helped promote her. “I’ve heard some of the polarizing things,” says the female staffer, “but that was not my experience with her.”

On the other side are women like Nora. Reading the complaint made the former politics reporter reflect on an interaction she and Gotthelf had in 2019. The 30-year-old says that while hiding in the bathroom from a copy editor who she claims used to follow her around the office, Gotthelf simply told her to watch out for the man. Upon reflection, she found that advice to be “really fucked up.” “You’re the female director of this newsroom,” she says. “You have the power to hire and fire people. Shouldn’t you protect your young female staff?” When the lawsuit came out, Nora texted me to say, “Stunning Michelle swept my own creepy colleague problems under the rug when dealing with her own.”

Throughout my reporting, a dozen sources also told me they’d heard about an alleged incident in which a Post editor, Paul McPolin, had propositioned a freelance reporter. When I called Meredith, the reporter in question, she confirmed that at a bar in 2006, McPolin had said he would make her a staffer in exchange for a blowjob. At the time, Meredith says, she declined the apparent offer, brushing it off as a mix of typical industry sexism and hard partying, since everyone was drinking. Two people who were at the event say Meredith told them about the interaction shortly after it happened. One said she seemed shaken. McPolin declined to comment, but a Post spokesperson said he “did not proposition the reporter.”

Meredith remembers later being asked in an HR meeting if she would like to file a formal complaint against the editor. She said it didn’t feel like a sincere offer. She needed to protect her job and feared retaliation. Looking back, Meredith realizes the incident was “more inappropriate” than she had thought at the time and wished she had been offered more support, especially from Gotthelf, who declined to comment on the whole ordeal. “Maybe Michelle should have been like, ‘Hey, you won’t lose your job,’” she says. She recently found an email Gotthelf had sent her during this time period, in which she followed up on the “handful of inappropriate comments” allegedly made by McPolin and told Meredith, “You are valued here … Call me if you want to talk.” While she says that the email might seem supportive on its face, it could also be a “management-covering-her-tracks thing.”

In one of our interviews, Gotthelf says she has “seen people who really should have been frog-marched out the door treated with more respect” than she was. Her lawsuit highlights this larger alleged double standard: After she complained, Gotthelf says, Allan was thrown a “retirement” celebration. She was told it would be her last day.

Gotthelf’s exit prompted a larger reckoning over a newsroom that toes the line between tough and toxic. In the past six months alone, more than 20 Posties have left, an exodus many chalk up to staffers no longer being willing to tolerate the newsroom. (A Post spokesperson denies this, calling it unreflective of exit interviews and noting that the editorial staff is actually growing.) This was the case for Nora, who says the pressure to pump out up to eight stories a day was so extreme that she felt chained to her desk. After an editor called her on her lunch break to ask “Where the hell are you?,” she mostly ate instant noodles and Skittles from the vending machine to save time and rarely went to the bathroom. (She says she got multiple UTIs.) To cope with the stress, and to get through election-year shifts that sometimes spanned 16 hours, she turned to alcohol, having up to five drinks a day. “The newsroom felt like a bit of a war zone,” she says. “You’re walking around on eggshells and just waiting for someone to yell at you.”

One field reporter remembers being yelled at so loudly by a senior colleague over speakerphone in 2020 that her friend, who was driving, pulled off the highway in shock. Some told me they’d been sexually harassed by freelance photographers and felt that the company put no safety measures in place to prevent that kind of power abuse. (A company spokesperson said that “the Post has a strict sexual harassment policy for both employees and freelancers” and that the complaints were addressed and the freelance photographers terminated.)

Several former reporters working for the Sunday paper say they felt trapped in a constant state of fear by their editors. One they described as having a particularly volatile temper is McPolin, who runs the section. Adam Schrader, a former web producer and reporter, remembers watching McPolin become red-faced while “screaming really, really loudly” and swearing at a junior staffer over a misunderstanding in 2019. (The issue went to HR, and the Post says McPolin’s outbursts are “in the past.”) While multiple staffers who have since left the Sunday paper say they were on the receiving end of his tirades, some say McPolin also vehemently defends his reporters and turns them into better writers — and note that he wasn’t the Sunday team’s only problem. Multiple reporters remember being reprimanded by a different editor for requesting time off; another says they were berated for not filing a story fast enough. A few sought therapy as a result of the stress. “I was thinking about walking in front of a bus so I wouldn’t have to go to work,” says a former staffer. “I still have a version of PTSD from that experience.”

Nobody expected the Post to be woke, but the culture could feel unnecessarily cruel. Some on the metro desk say Gotthelf felt like the invisible hand empowering her own team to mistreat reporters. “I thought she was this feminist icon,” says Nora. “But she turned out to be just as cold as the rest of them.” Posties described Gotthelf’s managing editor, Dan Greenfield, as the trusty henchman who faithfully carried out her dirty work. While some called him fair and professional, others say he has a temper that can flare up, especially when the Post is scooped by the competition. A former staffer says they filed an HR complaint against Greenfield at the end of 2021 for his hostile behavior, which the Post says was resolved. The staffer considered him “as much of the problem” as Gotthelf, “and in some ways maybe more because he helped to embolden her.”

Posties say that while Gotthelf wasn’t a yeller, she had a cutthroat leadership style, and the mere sight of her purple-unicorn avatar popping up on Slack made them flinch. Max Jaeger, a former reporter and editor, remembers Gotthelf once calling him to say, “I got this story. It sucks. I need you to fix it,” even though he was the author. “It’s a funny story, but it also feels bad,” he says. Sometimes her reprimands were public. She humiliated one photo editor in a morning meeting for mistakes that had been made by overnight staffers, according to a Postie who witnessed the berating. “We’d all be slacking each other about how we’re so embarrassed for him,” the staffer says.

Dan Good, an editor on the overnight shift who started at the Post in 2012, once got an email from Gotthelf that has haunted him ever since. When he messaged her about being disappointed to see that a story he’d published online about Jennifer Lopez performing for dictators had been written by another journalist for the paper’s front page, she copied his bosses on a cutting response. “We took nothing from your story because there was NOTHING to take,” she wrote. “You have no idea what you’re talking about, so cut the nonsense. Personally, I think we’d be better served with an overnight editor who isn’t patting himself on the back for doing the bare minimum.” Good admits his story was based on a press release, but he was still shocked by the vicious delivery, especially since he was “so low on the chain.” He started looking for another job and says Gotthelf’s message “really made me question if I belonged in New York media and if I was good enough to hang with these people.”

One former Postie describes Gotthelf as a character out of Mean Girls. “If she hated you, she was a terrorist,” says Chloe, a staff reporter. But she adds that Gotthelf also chose young women to mentor, and those in her inner circle tended to be extremely loyal because she would “do anything for them.” The day I was scheduled to interview Gotthelf for the first time, a few of her defenders suddenly wanted to talk. They told me that while she could be direct and cutting, any comparison between her and Allan’s behavior is absurd. “It’s not even in the same universe,” says one editor. Another former editor says they’d never seen Gotthelf do “anything that crossed the line in all my years of working with her.”

Gotthelf’s supporters say her “tough but very fair” leadership pushed staffers to write sharper copy and produce the kind of accurate, nonpartisan journalism that wasn’t valued by Allan or Murdoch. “She was a hard-driving, tough-as-nails, blood-and-guts news editor who did what she had to to get stuff done,” one editor says, “But she’s not the villain of the Post.” Some found her frankness refreshing — her signature feedback was “Make it not suck” — since her colleagues always knew where they stood. “If she doesn’t recognize talent in someone, she’s not afraid to say it,” Kemp, the former editor, says. “That might come off as bullying. But when you’re editor-in-chief, you gotta make decisions.” Maybe she was being held to a double standard: “People are used to their male bosses being curmudgeonly and talking shit,” says a former staffer, but when a woman does the same thing, “it ruffles them the wrong way.”

Gotthelf admits that she’s “very, very snarky” and “very to the point.” Sure, sometimes she could be “maybe a little too direct,” but when staffers came to her with personal issues, she says, “I would literally give the shirt off my back for anybody.” She doesn’t want to make excuses, but it’s impossible to “be a softie” with such an intense job. Sometimes she would get short with people and regret it later. “I’m so proud of all of the exclusives that we’ve broken and the stories that I had my fingerprints on,” she says. “And then there was that terrible part of I don’t like what I have to be.”

Even some of Gotthelf’s critics felt some empathy for how the environment might have shaped her. “As a woman in that place, you had to be absolutely ruthless,” says Meredith. “I didn’t have to deal with the internal politics. I didn’t sit in the middle of all those men.”

In 2016, Gotthelf had a small victory when, after complaining to HR about Allan’s alleged harassment, she says he was forced into what proved to be a temporary retirement. (Allan’s lawyer says this is untrue and that he wasn’t even aware of Gotthelf’s HR complaint.) Murdoch came to the newsroom to give him a backslapping goodbye, calling him “one of the most outstanding editors of his generation,” according to Gotthelf’s lawsuit. She was promoted to managing editor, an “obvious effort to protect” Allan and keep her quiet, she claims, and in 2019, Gotthelf became the editor-in-chief of digital, despite mainly having a print background. In multiple interviews, she has talked proudly about running the newsroom, boasting that “every reporter, and every … story came through me.”

That same year, Allan was brought back in an “advisory role.” Gotthelf says she was terrified by his return. Just a few weeks earlier, according to her lawsuit, he had drunkenly called to berate her for a story in the Daily News the Post had apparently missed. Gotthelf’s complaint says News Corp.’s CEO, Robert Thompson, and its head of HR reassured her that she wouldn’t report to Allan — in fact, her new employment contract guaranteed this. Still, “I knew he was going to retaliate,” she says. “And you don’t know when that shoe is going to drop.”

At first, Gotthelf says, Allan had “his tail between his legs” and was on his “best behavior.” But a few months later, he drifted back into his old role and became her “de facto supervisor,” per the lawsuit. (Allan’s lawyer denies this and says he remained a consultant.) There were a few high-profile controversies during Gotthelf’s reign as digital EIC, at least one of which she chalks up to orders from Allan. She says he forced her to remove a post about the writer E. Jean Carroll’s rape accusation against Trump, calling it “baseless shit” and ordering her to take it “fucking down.” When she told Thompson and HR that Allan wasn’t supposed to be her boss, Gotthelf says they responded that if he “tells you to do something, you do it.” (The Post denies this.)

Given Gotthelf’s powerful role, a few Posties thought she didn’t push back hard enough against these directives. Several sources felt she betrayed her own “golden reporter” on a 2020 story about the Biden family. Gabrielle Fonrouge was “like a younger version of Michelle: fearless, tough, and incredibly ambitious,” according to Nora. When the Post got its hands on files from Hunter Biden’s laptop, which came via Trump insider Rudy Giuliani, some staffers felt the intel had not been sufficiently corroborated. Management forged ahead with publication anyway, according to the New York Times, which would later confirm the scoop. The main writer withheld his byline, while Fonrouge, who per the Times “had little to do with the reporting,” had hers on the story and was thrust into a media maelstrom. Nora says it made her realize Gotthelf would “literally shank anyone. For Michelle to just throw her own protege under the bus like that was horrific,” she says. “You kind of realized that no one mattered.” (In response to a request for comment, Fonrouge says she is not authorized to speak on the incident.)

Whatever control Gotthelf had over the newsroom as digital editor-in-chief, she didn’t hold on to it for long. At the beginning of last year, Murdoch installed Poole, one of his loyal lieutenants from the U.K. tabloid The Sun, above Gotthelf. Many staffers thought Poole’s arrival would be the start of an inter-newsroom war that she was likely to lose. “I think she was completely redundant to Keith Poole, who fancies himself as the big digital guru,” says Laura, the former editor. “And so he didn’t need her.”

Before he left the Post for a second time, Allan ominously wished Gotthelf good luck and spent a few weeks briefing Poole, according to the lawsuit. She thinks her fate was sealed in November 2021, when Poole took her out for what she thought was a lunch meeting to discuss her expiring contract. Instead, she says he asked, “What happened between you and Col?” She told him about the alleged harassment, and a few months later, she says, she was canned. The Post disputes this account and says her disclosure to Poole “had no bearing whatsoever on her ultimate departure from the Post.”

Whatever the reason for Gotthelf’s exit, Good, who briefly rejoined the Post last year, says she seemed desperate to retain control, constantly sending Slack messages about stories and expecting immediate answers as a way to make sure her staff was on — in her words — “Team Michelle.” “I think she was trying to hold onto whatever power she could,” he says in an email.

Good hadn’t been around to witness much of Allan’s tyrannical reign, and reading Gotthelf’s lawsuit has complicated his perception of her as a power-hungry bully. “I saw what happens to somebody when they endure the suffering she did,” he says. “I do think she has good in her. I think that what happened to her both emboldened her bad behavior and forced her into this constant fear state.”

Staffers have already started to trickle back into the Post office twice a week, and Chloe, the reporter, says the environment feels different. “It’s just much less — what’s the word? — threatening? Aggressive? It’s like that air of terrorism has kind of dissipated.” An editor says there’s less pressure to “Go Go Go!” and do stories “Faster, Faster, Faster!” than when Gotthelf ran the newsroom.

The news that Greenfield would be promoted in the wake of Michelle’s departure elicited widespread groans. “It’s typical Post to give an older white man a job when they’re facing a gender-discrimination lawsuit,” Chloe texted me after the announcement. But since then, some Posties say Greenfield has no longer been ruling in the toxic style some staffers call “Old Post.” Then in March, another middle-aged white man left as the Post’s managing editor, and a woman of color was promoted to his spot, with another woman now serving as her deputy. Both are in their 30s and have a healthy approach to management, Posties say, yet not everyone is celebrating. One reporter says having an “intelligent and competent” female leader doesn’t change their opinion that the newsroom rots from Murdoch down: “You can’t keep blaming everything on Michelle, at the end of day.”

News Corp. initially tried to get Gotthelf’s case dismissed, per court filings, and in mid-April her lawyer told me she could no longer speak about the complaint or her life. Then, a few days before the publication of this article, the parties announced an undisclosed settlement, releasing a joint statement in which Poole and Gotthelf mutually praised each other. “The Post is in good hands with Keith Poole at the helm,” she said. “His experience in print and digital journalism bodes well for the future of the Post.”

The tune was different when I reached Gotthelf at the end of February. She was sitting in her home office, wearing a black hoodie and a pale-pink headband, surrounded by brown walls. She shares it with her boyfriend, and when I asked about the somber frames on the wall, she said, “Yeah, this is all Tom … he was a journalist for a long time and actually a really successful one.” Her chandelier, pink desk chair, and boa were still being held hostage at News Corp. headquarters. “They have my favorite teapot,” she said with tongue-in-cheek anger. “I’m very upset about that.” The pink walls of her office have been painted over, according to Posties, who say the space is now decorated with Greenfield’s Batman paraphernalia.

Full of intense energy, Gotthelf swiveled in her chair and told me she was “jonesing” to get back to work. Whenever she thought of how she was treated by the Post, her blood pressure would go up. “I’m getting the feels again,” she said, putting her hand over her heart and repeating the word “disrespectful.” “When you Google me, you are going to see ‘She sued for sexual harassment,’” Gotthelf said. “I don’t want this to be my legacy.”