At 19, freshly immigrated to North Carolina as an asylum seeker from Pakistan, I landed a part-time sales-associate job at Abercrombie & Fitch. It was the late ’90s. I was looking forward to having some pocket money and fitting in with the cool kids. Everyone who worked the coveted weekend shift at that Durham store was beautiful — slender, fit, dressed in jeans or khakis, plaid shirts, T-shirts, and flip-flops emblazoned with the name of the brand. My co-workers seemed carefree and confident and had a way of navigating the world I understood as uniquely American from watching exported TV shows as a kid. I noticed that all but one of the associates I met were white.

I was lucky, the manager said: “Everyone wants to work here.”

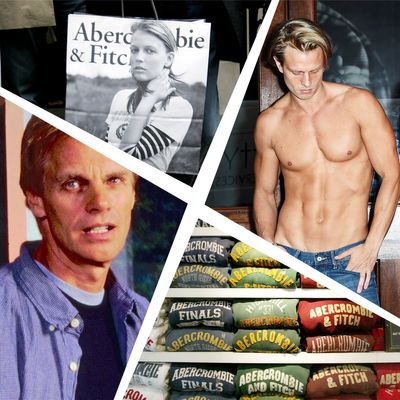

My first day on the job, my education began. After-hour training sessions focused on learning to identify the “all-American look,” how to upsell to a certain kind of “preppy” mom, and what kind of kid was “not a good fit” as a customer. Crew cuts and high blonde ponytails were a yes; durags, piercings, and black clothing were a no. On the sales floor, I was encouraged to flirt with my co-workers, act “sexy but laid back,” and be selective about which body types I actively sold to. Not everyone is meant to wear these clothes, I was told. Above all, I was taught to internalize that Abercrombie & Fitch was not a job; it was a lifestyle. I was to remember that I represented the brand even when I was not in the store.

My experience was that the more “Abercrombie” I behaved, the better friends I seemed to become with the other associates. I was invited to gossip behind the cash register and pulled aside to be told which boys were going to ask me out. I was given first pick on discounted stock and seasonal posters of shirtless boys and regularly scheduled to work with an associate who was a model for the brand and thus the most desirable of all my co-workers.

As my sense of belonging grew, so did the expectations of complicity. If an applicant didn’t look like they “belonged” in the store, I was told to let them know we weren’t hiring. I once watched a co-worker throw away a Black kid’s application the second he left the store. The kid looked like a model and was a student at UNC Chapel Hill. He even wore an Abercrombie T-shirt. Years later, I recall that moment as the shift in how I understood the discriminatory culture of the brand, but back then I was simply confused.

Some time later, I was told that the Black co-worker I had met should be fired. “He pocketed a necklace when the customer returned it, I swear,” one of the other sales associates told me. “You were there.” I remembered nothing of the sort, but my silence, it was made clear, was expected. The accused associate and I never shared a shift again, and I was never clear on what happened to him.

It was then that I realized my education often excluded people who looked like me — brown, Asian, Black, nonwhite — and I began to feel something was wrong. I started to understand that there was a “them” and there was an “us,” and that only by sharing in our common culture of shirt-folding and exclusivity could I overcome the differences between my co-workers’ background and my own. Belonging, I was learning, came with a price tag.

Watching the new Netflix documentary White Hot: The Rise and Fall of Abercrombie & Fitch more than 24 years after I worked there confirmed for me what I have suspected for a long time: I fell for a script. The brand was intentional in creating the ultimate aspiration — being part of the “in crowd” — and successful at making me and others like me feel privileged when we achieved it. I did not know that the managers were rating us on a scale “from cool to rocks,” as the documentary claims, or that there was a look book that described exactly what kind of hair employees were allowed (straight, neat, no dreadlocks on men or women). I did not know that the issues I was observing were not particular to our store, or that just as I saw Black people being actively discriminated against in Durham, the same was happening to Asian Americans on the West Coast. The brand has since taken responsibility for these practices in an Instagram post from the CEO, which states, “We own and validate that there were exclusionary and inappropriate actions taken under former leadership.”

In the years following that job, when I encountered shades of that exclusion in other workplaces, classrooms, and even my community of writers, I knew that my experiences in that store were a microcosm of American society. Prejudice seemed to be coded into the “all-American” model at Abercrombie & Fitch. I don’t know if I was hired because I was perceived to possess a not-too-brown look, though I don’t come close to presenting as white, or as the store’s token attempt at diversity. I do know that I was permitted to pass, provided I successfully flirted with the resident hottie in the front window, took no offense at Muslim-virgin jokes, understood that a touch or a grab here or there was an acceptable compliment, and mutely stood by if I saw or heard things that made me uncomfortable. The privilege of calling myself “all-American” made me complicit with a system that I did not fully understand and imprinted upon me values I would later reject. In a twisted way, I cannot think of a more appropriate orientation to America.

When I think back now, I can recall many Black, Asian, South Asian, and Latinx friends who wanted to work for Abercrombie, which had officially labeled itself as “exclusionary.” Some applied and got rejected. Others spent birthday or Christmas money buying the clothes in the hopes that having the right look might get them the job. The feeling of being manipulated and used, or that I was a token, was not a small cost to my self-esteem, either, but I was able to quit and leave that job behind. I was too new to America to fully see it then, perhaps too much of a good immigrant to say anything, but I fear now that some others may have paid a much higher price.

Last year, I repatriated to the U.S., this time with an American teenager of my own. I had hoped things would be different, but I have watched my son encounter a country much the same as that Abercrombie store from all those years ago. My son, more concerned with equity and uplifting the marginalized than I was at his age, and also more of an “all-American” kid, who plays all the sports I only pretended to play in the window of that store, still walks through our front door confused by others’ perceptions of him. I’ve watched him weighing whether to thank people for acknowledging his English and processing their surprise at his American accent.

I’m still haunted by the conflicting emotions of my Abercrombie days: how wonderful it was to belong, how ugly I felt watching that Black kid’s application end up in the trash, how white endorsement was presented as the only way to legitimacy. I felt isolated in my experience then, having no one to confirm my feelings. Now, I realize that I did belong to a group — though not the one that I had thought. In a strange way, it feels like validation.