I once tried to make a list of the many things my dad threw at my mom in moments of rage. It included keys, plates, batteries, cell phones, two-way radios, and flight helmets. I’m not even counting palms and fists. Once she was wearing sunglasses when he hit her, driving shards of the lens into the soft skin around her eye socket. I walked into the bathroom to find my mother with a rag in her hand covered in blood, her face still oozing. My father was there too, trying to close the gash with a butterfly bandage. That was him: always the hero; also the harm.

My brother and I weren’t spared. When we were small, my father used his belt as punishment. He’d catch us, hold us on his lap, and then strike our bare skin over and over again. It was only recently that I learned this is considered child abuse. Growing up it was just how it was. You made him mad. You got the belt.

Along with my goldfish dying and Jamie getting a Top Gun–branded plastic jet for Christmas, my childhood memories are spotted with the time spent with my mom plastering over the holes my father punched in the wall. If the damage was beyond repair, we’d hang one of my mother’s paintings and pretend it hadn’t happened. We had a lot of paintings on the wall.

Sometimes my father would come in and apologize. He’d ask for forgiveness. He’d tell me he loved me. But in the morning the whole cycle would start again. Every day brought the possibility of an explosion. His anger could be triggered by almost anything, but especially if he thought you were being weak or sad when he thought you should be happy.

On one of our fancy vacations to Hawaii, when I was in seventh grade, I was moping around the way preteens do. I had my period. It was new and it made me emotional. I missed my friends. I worried they were doing fun stuff without me. When I was doing my nails on the floor of our hotel room and smudged a finger, I started weeping out of sheer adolescent confusion.

My father lost it.

“Stop crying!” he yelled at the top of his lungs. “You’re in Hawaii.”

I darted for the closest door as he lunged in my direction. It was a small bathroom in the luxury suite he was proud of that weekend. I locked it and shook in terror as he banged and kicked and yelled. If he broke it down, I thought, he’d hurt me. Really hurt me. I don’t know how long I stayed in there, but long enough for him to calm down and leave the room. Long enough to feel safe again.

I put up with it for years. The whole family did.

But by my senior year of high school, I’d had enough of my dad’s insults and his anger. When he started laying into my mom one day, I just snapped.

“Fuck off,” I said. “Get out. We don’t want you here. LEAVE!” He took two or three hard strides in my direction and I couldn’t tell you if he spoke or just seethed. The next thing I knew something hit me in the lip, his fist, a short, sharp jab that broke the skin. I remember the taste of blood.

“How dare you,” I screamed. “I’m your daughter.”

I punched him back, a solid, straight arm blow to the chest, hard enough to rattle my forearm and make my knuckles crack.

“Fuck off,” I said. “Now.”

My father left. It was quiet then.

I told my mom we should call the cops. It would send him a message. Tell him this wasn’t okay. He needed to get help and stick with it. We spent a lot of time gaming it out. But then we also thought of his name. His recognizable fucking name. If it showed up in a police blotter, there’d be news coverage. Bob Tur arrested for punching daughter, abusing wife.

What would that do except make it harder for my parents to work. Harder for them to make a living. Harder to be Bob Tur, the famous news helicopter pilot and family man. My mom shot all the footage but my dad was the brand. I hated the idea of hurting him and us. I hated it even more than I hated how he treated us. So we decided to live with it. We had no choice.

People always want to know why. They want to understand what made Bob Tur such a hothead and what made his nice, calm, seemingly normal wife, Marika, stay with him for so long. It’s a question I’ve asked her and myself more than a few times. When it comes to my mother, I’m not sure there’s a clean answer. But my father’s side of the story seems pretty simple: he was beaten himself.

Bob Tur was born in Los Angeles in 1960 after a pretty nineteen-year-old named Judy Offenberg met an already world-weary garment manufacturer named Jack Tur. Jack had already been married and divorced and fathered a child. As the story goes, Judy refused to marry him unless he cut ties with his first kid. He did. And while the marriage that followed may have always been doomed to violence, I think the loss of that connection — the guilt and the grieving on both sides — darkened every waking minute.

Jack was a gambler. At the racetrack, he’d hand his son Bob the rent money and tell him to protect it, to keep it from him. Then he would beat it out of him. The gambling led to losses which led to evictions or sudden abandonments. Sometimes my dad would come back after school to find the family gone. Other times he’d be shaken in the night and told to leave everything behind.

Along with the sudden evictions, my father suffered sudden acts of violence. Nose broken by his father’s fist. Hand stabbed with his father’s fork. Face slashed by his father’s keys. He is missing a piece of his ear because his father sliced it off. In his mid-teens, my dad ran away. Everything he did after that was a continuation of that first attempt to find safety. When there’s no going home, no going back, nothing but the future, you find a way to make it, or you fall apart trying.

I always felt like I knew why my mother stuck around. There was the marriage, of course. My brother and me. The money. The inertia of a shared life. She also had sympathy for what my father had been through as a kid, himself. She felt like she understood him, and to understand is to forgive. All that is true, and yet I had failed to consider my mother’s own ambitions.

She was born in Los Angeles in 1955 to a woman who dreamed of a career. Connie (my grandmother) was born to a rich family of Greek immigrants in Florida in 1918. She traveled the world. To Cuba. To Paris. Back to Greece. She floated across the ocean on luxury liners, rumbled through Europe by train. There’s a picture of Connie in Egypt as a child on the back of a camel.

She also loved journalism and journalists. Connie kept a metal press ID card for the Paris bureau chief of Time magazine in a locked box for decades. We don’t know the story behind it, but we think it’s a lost love. A life that might have been.

Connie’s problem was timing.

She was a woman of the early-to-mid-twentieth century, which means she felt forced down a particular path of marriage and children, though she fought it for years. After her parents lost money in the Depression, she went to the University of Miami to study biology. She found work in the burgeoning field of blood analysis. She loved it so much she intended to stay with it even after she met my grandfather Gerry, a young man from Brooklyn who wanted to be the Greek Frank Sinatra.

It was Connie’s career, not Gerry’s, that brought them to California. She worked for a blood bank while Gerry used a college degree in engineering to get into the pool business. She continued to put off children past the age of 30, 31, 32, 33. At 34 her luck ran out. She got pregnant with my mom’s older brother and lost her job. Bye-bye career. She got fired or quit. Either way, no such thing as having it all in those days.

My mother wanted her life to be different and Connie did too. Maybe that’s ultimately why my father’s early episodes didn’t scare my mother off. She was willing to deal with some turbulence on the way to a dream. She wasn’t willing to live another boring life.

When I think about what might have been I think about my father’s mother. If anyone could have fixed things it was grandma Judy. Although we were never to call her that. “I’m too young to be a grandmother,” she’d say laughing, a cigarette dangling off her red painted lips and her hand combing through her platinum blonde bob.

In late 1997, she went to the hospital with a pain in her toe and doctors discovered she had stage 4 cancer, which had spread through her body. I found out how truly bad it was when in a free period before the end of the school day, I called my parents to remind them to come pick me up.

I got the answering machine at the hangar.

“Hi, this is Los Angeles News Service. We can’t come to the phone because we’ve had a death in the family. Judy Tur died today.”

I was on a payphone outside of the school library. I stopped breathing, dropped the receiver, and sat on the ground. Did I just hear what I just heard? Did my parents really just announce my grandmother was dead on an answering machine? Was it so important to tell their news clients before they told their daughter?

I stood up, hung up the phone, and walked into the library. I wasn’t crying. I was in shock. And I had to sit there with it, alone, for another 30 minutes until school got out.

I tried to tell myself that it wasn’t happening. That the machine was wrong. I just saw her last night. She was in the hospital and yes she said she was having a hard time breathing. But she looked alive. Not on the verge of death. She was only 57.

I couldn’t imagine life without her. She was my protector. When I was scared or worried, I’d sleep in her bed and she would tickle my arm for hours, until everything melted away. If that didn’t work, she had other tricks. Grilled cheese. A root beer float. Once in middle school, I complained to her about a boy who didn’t like me back. “Point him out to me,” she said with a wink. “I’ll beat him up.”

I didn’t even say goodbye.

I hadn’t even wanted to be at the hospital the night before. I was 14 and I wanted to be at home, on the phone, talking with my friends. I didn’t believe she was that sick. I simply couldn’t face it. She was everything to me and my brother. In some ways, more my mother than my actual mother. And she was holding us together. If she were here, everything would be different. We’d still be a family.

After the funeral, my father fell apart too. Some nights he would sit at the foot of my bed crying. He’d never cracked up so completely before. My parents tried to stay on top of their business. But those were Judy’s deals. My parents had her files but not her relationships.

Their monthly revenue slid southward. From six figures to five figures to four figures, even less. Difficult decisions loomed. Move into a smaller house? Lose the fancy cars? The private school? The health insurance? The hangar and the helicopter? The math didn’t work on all of it. Something had to go.

I remember hearing that the best way to teach a kid about money is to lose a whole lot of it. That’s certainly true. I went from oblivious to aware in a matter of weeks. I learned what a bill collector was and to hang up on them. For continuity and probably pride, my parents decided to stay in the house and keep the cars. They also kept us enrolled in private school. But they cut our health insurance. And they said goodbye to the two biggest expenses in their lives, the two things that had defined them and our family for so long: the hangar and the helicopter.

On March 17, 1998, two months after Judy’s death, my parents took the helicopter out for a last flight, late in the afternoon, the sun low, the light golden. As my father flew, he tried to pre-tape some lines, little introductions to the best stories in the Los Angeles News Service archive, something they might be able to package and sell. My mom pointed the camera at my dad and started rolling. But almost immediately it turned into a fight — a blowup about whether she was keeping the shot straight.

“I don’t want excuses,” my father snapped. “I’m going to tell you this for the last time.”

He seemed to mean it as a threat and my mom seemed to take it that way.

“Don’t hit me,” she said. “I can’t tell. I’m doing my best.”

Back on the tarmac of the Santa Monica airport, they powered down and my mom placed the camera on the rear seat of the helicopter, looking forward, capturing the instrument panel and my parents from behind. They sat still for a while, shoulders slumped, totally silent except for radio chatter and rotor noise. Then the blades slowly stopped spinning.

Suddenly, these two impossibly adventurous, ambitious people, who found every breaking news story in Los Angeles, who flew above fires and shootings and police chases, who found O.J. on his slow speed pursuit, and filmed the beating of Reginald Denny, the seminal moment of the 1992 L.A. Riots, were two lumps on the couch. They took down their maps of Los Angeles. Turned off their police scanners. It seemed like they had given up on the job, stopped fighting for the next story.

I decided then that I’d be a lawyer. If not that, a doctor. Definitely not a journalist. The little girl who had loved the feeling of flight and the adventure of a new story was passing on the family business. In my high school yearbook, I wrote that I wanted to become a Supreme Court justice. My parents loved the idea.

“Someone’s always going to need a doctor or a lawyer,” my father said.

I left for college with nothing to show from my parents’ old life. After loading my stuff into the dorm at the University of California, Santa Barbara, though, my father handed me something wrapped in a cloth. I was seventeen and surrounded by kids in flip-flops.

“For protection,” he said.

I unwrapped the cloth and saw my grandmother’s revolver, a silver .38 snubnose that my father insisted she carry.

“It’s not loaded, but an intruder won’t know that.”

The truly crazy thing is, I took it. I put it in my nightstand. At the time it didn’t even seem weird.

A note about pronouns: if you built a human being from scratch and filled their brain with the New York Times op-ed page and the GLAAD media reference guide, they’d never let you down. But I wasn’t built from scratch. I had a father, Bob, who is now my father, Zoey. I support her transition and I applaud my father’s courage. I also still struggle with my father’s past, which is a major part of this book. For that reason, Zoey will be Zoey from the moment of her announcement to me. Before it, Bob will be Bob.

Both she and he will always be my father.

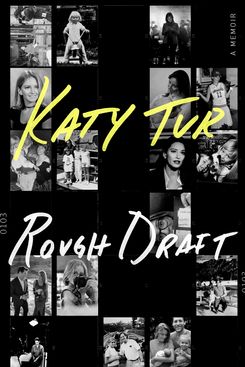

Excepted from ROUGH DRAFT by Katy Tur. Copyright Ó 2022 by Katy Tur. Reprinted by permission of One Signal Publishers/Atria Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.