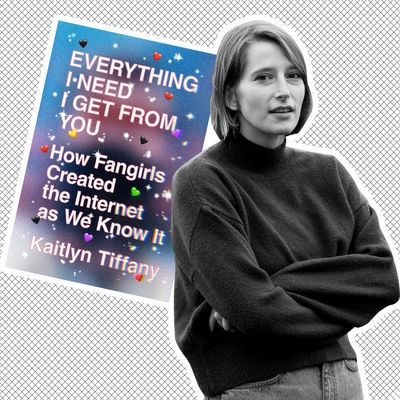

Fans rule the internet. They are responsible for our online vocabulary, the topics and news items that trend every day, and, most importantly, memes. So many memes. In Kaitlyn Tiffany’s new book, Everything I Need I Get From You: How Fangirls Created the Internet As We Know It, the author explores a subset of fans consisting of passionate women and girls known as “fangirls.” “The criticism of fangirls is that they become tragically selfless and one-track-minded,” Tiffany writes. “The evidence available everywhere I look is that they become self-aware and creatively free.”

The book positions “fangirling” as a pivotal subcultural movement and explores all facets of it — from an analysis of the screaming fangirl trope used to malign them to a look at how fangirls have turned fandom into a business and all the myriad ways they’ve leveraged their passion into very real political and social power (by supercharging a male celeb’s career by dubbing him the internet’s boyfriend or forcing the world to bear witness to Britney Spears’s conservatorship battle). Just look at Meilin Lee, the protagonist of Pixar’s latest animated triumph, Turning Red. Mei is a fangirl whose obsession with fictional boy band 4*Town is one of the single biggest driving forces in her life. Her determination to express her love for the band propels the movie forward and showcases how well organized, mission-driven, and relentlessly innovative fangirls can be. When the movie premiered, IRL fangirls saw themselves in Mei and began sharing their stories of writing fanfiction and other devotional acts to pop stars in ways others may find embarrassingly earnest but give them pride (“we are cringe we are legion”).

Whether wielding their power to call attention to homophobia and online bullying, produce unofficial online concerts during a pandemic, or spam police in service of racial justice, the actions of fangirls have become undeniably newsworthy. Tiffany feels it’s past due to take fan enthusiasm — hers included — seriously. After all, she writes, “the screaming fan doesn’t scream for nothing.”

Your book’s title is inspired by a One Direction lyric. You’re a Directioner, but you make it clear early on that this is not a book about One Direction. What is it about?

I wanted the book to be about the ways that fandom created not just the mechanics of the internet but the cultural experience of the internet. As a fan, I had been watching the way that a subculture dominated by girls and women was evolving over the 2010s and all the interesting (sometimes really exciting and inspiring, sometimes dark and weird) things that they were doing. I felt like it hadn’t been observed as intently as what boys on the internet — and I’m obviously generalizing — had been doing on Reddit and 4chan. And Gamergate in the lead-up to the 2016 election. Those cultural forces were equally real, but they seemed more dangerous or urgent to people. I felt like fandom was equally important in causing cultural shifts online and in culture and politics. Talking about it through my own experience with One Direction fandom was the easiest way to narrow down this broad landscape.

You got pushback from boy-band fans when you initially announced this project. What do you think they were concerned about?

It’s natural as a fan to be protective of the borders of a fandom, because it’s been dismissed and maligned so often by critics and people who aren’t participants in it.

There is a sense that fandom is private and not something to project to the world. If you’re not in fandom, a lot of what you probably have seen of it is aggressive, constant posting on Twitter. But there’s a flip side to that, which is Tumblr — the private, insular space of fandom. There’s a pretty understandable reaction from these people, who have spent a lot of time in these spaces and who care deeply about them, being like, “We don’t know you. We don’t trust you. You’re here to make a quick buck.”

But when I put up a Google form asking anybody who was willing to fill out a little survey and maybe set up an interview for the book, 300 people filled that out. I talked to so many fans who were funny and interesting and excited to talk about fandom. Because it’s not something you get asked about seriously very often.

You argue that early internet fan pages were the original social networks. What do you mean by that?

Fan pages and email Listservs like Yahoo! Groups would’ve been proto–social networks in the sense that they were moving beyond the internet as a collection of static web pages. Fan sites, even though they were somewhat static, would often link to each other and create what was called “web rings” at the time. People became known quantities within the fan-site spaces, and there were even sometimes rivalries about who could get the best new photos of whatever musical act. The Backstreet Boys, for example.

Fans were always breaking things — finding new functionality in each iteration of online life and figuring out new ends to which you could put tools that other people might have been taking at face value and only using the way they’d been demonstrated. Fans would be figuring out, Okay, how can we interlink these blogs? How can we turn this Listserv into a file-sharing, peer-to-peer network so that we can get bootleg copies of this concert video? They were always pushing each new technology to its next step, because they had something specific to do with it. They weren’t just tinkering. They were coming online for a specific purpose.

One of the experts you interview, Henry Jenkins, is known as the father of fandom studies, and he said something interesting: “The entertainment industry is a tool or mechanism for fandom, but it’s not what fandom is.” Could you expand on that?

Yeah, his original revelation in his first book, Textual Poachers, was that contrary to early ideas about what people were doing with television — which would be to sit on the couch and be a zombie and receive it, passively eroding the American mind — a lot of people were taking things and twisting them up for their own purposes. Like writing fanfiction or doing cosplay. He was talking about how fandom exists outside of the passive or expected fan behavior of spending money on a commodity that’s been created for them by the entertainment industry, then marketed to them in this one-way relationship.

In the case of boy-band fandom, there’s the stereotype of these silly girls who are asking their parents to spend all this money on dumb stuff (a lunch box, perfume, promotional life-size cardboard cutouts of Niall Horan) and that that is what fandom is — being a dupe, being a capitalist pawn, wasting time, wasting money, being frivolous. Obviously, it would be false to imply that fans don’t do some of that stuff and that there isn’t some consumerist joy in having that cardboard cutout, but what Jenkins was getting at (and a point that I think is really important) is that it’s just one outward expression of something that’s really personal and complicated. Fans are interested in the industry. They’re interested in learning how it works. They do like to buy cool T-shirts, but that’s pretty marginal to what it means to be a fan.

Tell me about the research process for this book. You combed through Tumblr and a lot of old social-media posts and even made a pilgrimage to L.A. to the site of the infamous Harry Styles vomit shrine.

It was hard at first, because so much of the book is talking about this time period (2013 to 2015) that was the peak of my One Direction fandom — when I was spending the most time on Tumblr or Twitter or watching music videos over and over. It was hard to sit down at the computer and be like, Okay, how do I find entire lost years of my life online? I got out my college Tumblr and looked through everything I had liked or reblogged to see which pages were still active and whether it was possible to reconstitute some of the broken links using the Wayback Machine. There’s probably a lot that I missed going about it that way, which is kind of frustrating. It’s hard, because the internet decays in this really sad way.

I went to Los Angeles partly because it felt lonely and isolating to be looking for these relics that might not be there. It was exciting to think about like, Okay, so it’s hard for me to find the conversation around this vomit shrine. I remember when everyone was talking about it, and I can find some of the images that I remember around it, but it would feel good to re-situate myself in the weirdness of that story. I went to L.A. to see the shrine, then talked to the person who originally made it and has continued it as a joke.

As you point out, fans are engaged in archival work all the time.

Definitely. They end up being one of the most vital research tools. When I was at The Verge, I wrote about this Tumblr called “bad 1d imagines,” which was just a collection of microfiction — like a meme or a picture of Harry Styles that says, “Imagine you and Harry Styles holding hands on a Ferris wheel” or something. But this was a collection of really, really weird ones. One of them that’s quoted in the book (and that was in the story) was like, “Imagine Niall Horan crawling inside your ear. You tell him to stop, but he is in there.” When I was starting to work on the book, I remembered I loved those, so I wanted to make sure I included them. When I went back to look at the blog, I realized that in the intervening several years, the person who was running it had become an amateur historian or archivist of this fandom. People were asking her things like, “Do you remember this meme from way back when?” or “Do you remember this zany post that everyone was cracking up over?” And she had an uncanny ability to find basically anything anybody asked for, which was amazing. I was so interested that she was doing that work, so that became another thing I wanted to describe.

I love that fangirling is something you bonded over with your mother. For her, it was Bruce Springsteen; for you, 1D. What did that experience teach you about fangirling as a generational practice?

As a kid, my mom being really into Bruce Springsteen was something I didn’t understand. I describe it in the book — this hazy memory of her having a frustrating day and turning on Springsteen and zoning out. I remember feeling a little distant from her. Not in a negative way but maybe in a child’s way of starting to understand that your mom is a person. It’s been interesting and informative for me to think about how fandom could evolve and change but always be part of people’s lives and the way that they mark time or understand themselves. Once I had experienced intense fandom and the way that it could structure my life, it made me understand my mom more. I thought it was important to talk about, even though it didn’t have a ton to do with the internet.

After an emotional heartbreak in my early 20s, I serendipitously heard this Springsteen song that my mom had really loved as a teenager and I had this thought — that I will never understand what my mom was like as a teenager and she will never understand exactly what I’m feeling right now, but we can both understand what is transcendent about this song. It was important for me to put that in the book to challenge the narrative of fandom as something that’s limited to one phase of life. It’s bigger than that. It can connect you to other people in a way that’s not superficial. It can be something that’s important to you throughout your life — even if it’s not going to be something you indulge in all day, every day for your entire life.

This interview has been edited and condensed.