Growing up, I could never imagine being pregnant. Like many trans people, I dealt with puberty by creating a lot of mental space between myself and my body. I didn’t know what I was, but it couldn’t be this.

It’s not as if I was hurting for positive portrayals of femininity. In addition to my parents’ feminist politics, adults in my life spoke often of femininity as both divine and beautifully varied, from warrior women to Mother Earth. I liked these images, but they didn’t feel like me. Pregnancy and birth were especially disturbing, visceral acts that threatened the mental distance I’d constructed between myself and my physical form. Birth was for women, so it couldn’t be for me.

In my early 20s, I connected with other trans folks while working on my graphic novel about gender. I learned that we all navigate our relationship with our bodies in different ways. I stopped looking at different traits as masculine or feminine, and instead came to view my body with a more matter-of-fact attitude. I have a uterus. Many people have uteruses. Many women have them, but not all. Some transgender men and transmasculine nonbinary people choose to remove or ignore them, but not all. I was on a hike in the woods in 2014 when it clicked into place. My worth and identity are not determined by my fertility, or having (or not having) a specific organ. Carrying a pregnancy is simply an ability some people’s bodies possess, and maybe mine was one of them. It was my choice to find out.

A few years later, my spouse and I started talking about becoming parents one day. I realized I wanted to try. We discussed at length whether I really wanted to carry a pregnancy. It meant coming off of testosterone, and I dreaded being perceived as a woman as my appearance lost the careful balance of androgyny it had managed to take on after two years on T. But ultimately, I knew my body was not for other people. I wanted to know what my body could do. I wanted to experience the plus side of the organs I was born with. I wanted a child who is biologically related to me.

Eventually, we officially started the process toward becoming parents. We did all the recommended steps: I went off testosterone so I could pursue fertility treatments, my labs all looked great, and my spouse and I initiated the process required by our state for both of us to be legally recognized as parents of our child. But three years of frustrating red tape, thousands of dollars, and six failed IUI attempts later, it just wasn’t happening. I started having regular days set aside for mostly crying — isn’t this what bodies like mine are supposed to be able to do? What was the point of all of that dysphoria if I couldn’t even do this? But I wasn’t new to feeling betrayed by my own body: The same tools that helped me cope with gender dysphoria proved incredibly helpful in coping with infertility. I connected with other trans people going through the same thing. I reminded myself that my body’s value isn’t in what it looks like or what it can do. I spent a lot of time lying on the floor, or going for walks, or doing anything that helped me inhabit my body with acceptance.

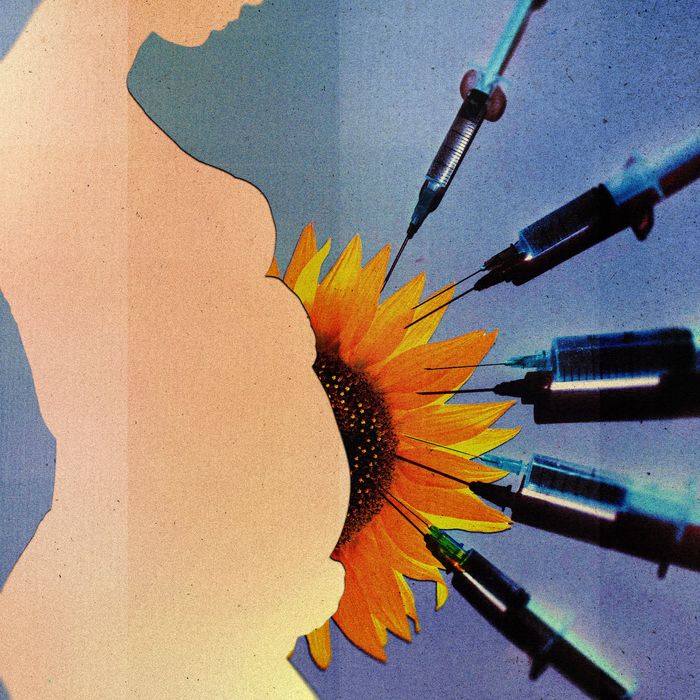

I ended up needing IVF, an intense process involving dozens of injections, daily exams and doctor’s visits, and three surgical procedures. I relied on what I had learned from supporting my spouse and friends through surgeries; where to stand, when to reach for a hand to hold, the fact that medical procedures could not only be endured but were incredibly worthwhile in the end. The hormones I was injected with changed my moods and made my body feel strange. But I was already familiar with the way hormones could affect me. A brief stint on birth control pills years prior had given me the lowest depression of my life, but being on a low dose of testosterone had helped me feel more at home in myself than I ever had. I knew I could get back to a hormone mix that felt good again someday. After a few months, we did our first embryo transfer. I got my first positive pregnancy test two weeks later.

The strangeness of pregnancy delighted me. I had expected to feel dysphoric, alienated from myself and despairing for it. After all, the internet abounded with articles written by cisgender women who felt their bodies weren’t their own anymore after they became pregnant, who didn’t recognize themselves in the mirror as their bodies changed. These stories echo the way gender dysphoria is experienced by many trans people, including me. Before pregnancy, I read these accounts and imagined my existing gender dysphoria growing bigger and bigger as my body swelled.

But once I was actually pregnant, I loved those articles. I was used to feeling like my body wasn’t quite my own, but I wasn’t used to seeing this talked about by so many other people in mainstream places outside my pockets of the trans community. Having so much company was comforting and allowed me to embrace the weirdness. I relished the kicks and movements inside me that I had no control over, the way joints loosened and my belly swelled. I felt like an eldritch horror, but in the best way. “I have more bones in my body than anyone else here!” I would announce to my spouse and friends with a broad smile. The fact that I had chosen the experience, knew it was temporary, and had tons of support all turned my imagined hurdles into a pretty fun ride.

But there was terror, too. Not far into my pregnancy, I started bleeding. A lot. Panicked, I called my fertility doctor and was brought in for an ultrasound. I braced for the worst. Then the ultrasound played the rapid thump-thump-thump of healthy embryonic cardiac activity. The bleeding was from a condition called a subchorionic hematoma — a little pocket of blood that could be seen on the ultrasound. They usually resolve in a few weeks, maybe a couple months at most. But mine didn’t. I carried it to the end and eventually developed a chronic placental abruption, a dangerous condition in which the placenta partially detaches from the uterus. I had six incidents of sudden and dramatic blood loss, all the way into the third trimester, and was hospitalized repeatedly toward the end.

I deployed every coping skill I had and borrowed some new ones from other trans folks. I knew how to advocate for myself with health-care providers. I thought back to when I was on hormone replacement therapy and felt truly comfortable and good in my body, and knew that I could someday feel that way again. In my mind, I repeated a refrain: “I chose this. I chose this. I chose this.”

Being trans brought on difficulties, too, especially with health-care providers. The words other people use to describe me can indicate whether they’re seeing me as an individual, whether or not I am safe with them, and, if they’re a medical provider, whether or not they’ve read my chart. During my first hospital stay, nurses and staff repeatedly misgendered me and asked inappropriate questions. “So these pronouns are optional, right?” No. “Do you regret being on testosterone?” No. “Don’t you think being trans puts limits on what being a woman can mean?” No, much the opposite! I was frustrated by my inability to explain why gender-neutral language mattered to me, as if I should be coherent while lying on a hospital bed and facing down my worst nightmares at four in the morning.

Like many trans people burned by the health-care system, I found myself tempted to avoid further medical care and skip tests, even though my situation was mortally dangerous. Instead, I got practical survival tips from my closest trans circle on how to navigate health care. Between hospital stays, I wrote up and printed a handout to give to hospital staff that explained my relationship with gender and why it mattered, and addressed frequent questions. I also reached out to my OB and to people who I knew were allies on the labor and delivery floor. At their request, I made a formal complaint to the hospital and clinic so that they could have more backing and resources to push for change.

The work that people did to improve the hospital environment was stunning. During my next hospital stay, it was like I was at a different place. I was treated with respect, no one asked me irrelevant questions, and when I was occasionally misgendered, people almost always corrected themselves.

The work the staff did brought home the fact that they cared that I was there, they cared what happened to me, and they wanted me to feel safe. This helped my spouse and I make one of the toughest decisions we’ve ever faced. Tests showed our baby was losing a substantial amount of blood at seemingly random intervals. The options were to deliver seven weeks early, possibly before our baby was ready to breathe or eat on their own, or continue the pregnancy and risk a life-threatening hemorrhage. We chose an early delivery. It turned out to be the right call. A month after delivery, we’re both alive, safe, and at home.

Now, in the sleepless weeks of early parenthood, I am gradually remembering how to inhabit my body in a more stable state. I am no longer a ticking time bomb of blood loss and looming tragedy. As the terror fades, the pride remains. My body is changing, muscles growing, hair falling out. After seeing the many transformations my body has undergone, I’m less intimidated thinking about future changes my body may experience as I age and pursue transition again. We don’t get to choose what challenges our bodies give us, but we can decide how to work with what we’ve got.