My 11-year-old daughter’s wide eyes narrowed, her lips pressed into a thin line — as if I’d suggested ridding our house of all screens, permanently.

“It’s summer!” A whine creeps into her voice. Yes, and it’s just a monthlong Mandarin class.

I’m anxious — trying to shore up nearly a decade of Mandarin as she’s balanced on the precipice of a new phase. She’s heading to a Mandarin-less middle school and leaving behind her bilingual elementary school where half her day was in Chinese.

She stands in the doorway — long, dark hair framing her face — not budging. Over the past few months, she’s shot up several inches in height, little-kid roundness replaced by angles and planes.

While her younger brothers, ages 6 and 9, still happily switch between Mandarin and English, it’s increasingly difficult to coax more than a word or two from her. Sometimes, when my parents visit, or when my youngest’s former babysitter comes by for an afternoon, she’ll bust out an awkwardly phrased sentence or two. But when I try to engage, she rolls her eyes and exhorts, “Speak English, mom!”

I don’t — I can’t — blame her. Conversing in Mandarin doesn’t come naturally to me either.

Decades ago, Mandarin was all I knew. Although I was born in the U.S., I didn’t learn English until preschool, when I was thrust into a monolingual classroom. There, English was inexorable, with the power to erase all else in its wake. To stem the tide, my parents — like many first-generation Chinese immigrants of that era — enrolled me in Saturday Chinese school.

By the time I was 10, it had become a chore to check off in the most perfunctory of ways. The Friday evenings before exams, I’d cram lists of vocabulary words — the spindly strokes, from which words materialized, fleeing my brain before the teacher had even collected our tests. And as my ability to express myself in my first language plummeted, so did the desire to use it.

I longed to fit in at school; at the church across the street where my nonreligious parents had inexplicably signed me up for choir; at the sleepovers that I mostly skipped anyway thanks to my Saturday morning schedule and later stopped receiving invitations to altogether. I longed to avoid the scorn I had seen strangers direct at my parents when they stumbled over unfamiliar syllables or swapped their pronouns (he and she have identical pronunciations in Mandarin). Sometimes, I’d jump in as an interpreter, as if to say, “I may look different too, but I speak English. I belong.” Once I asked a librarian where the new books were shelved and she responded by complimenting my English. My cheeks burned with equal parts shame and pride, but I didn’t correct her.

The extent of the language loss hadn’t occurred to me until years later when a grad-school classmate chuckled at the halting Mandarin I unearthed when I discovered she hailed from the same province as my dad. “Not bad for a lǎo wài,” or foreigner, she joked.

I don’t know what my father thought when I could no longer communicate with my Mandarin-speaking grandparents. Or when I begged to stay home while he and my mother made their weekly 40-minute drive to San Francisco for groceries — fish plucked from murky tanks and leafy heads of jiè lán, a bitter Chinese version of broccoli. Now on the receiving end of my daughter’s withering looks, I imagine he felt rejected.

It’s a natural, even expected, developmental phase: tweens and teens pulling away from their families. But for immigrant families — for whom language, culture, and customs already divide children and parents — the separation can feel especially charged.

It’s not just about carving out a separate identity. It’s a repudiation, even if unintentional, of a parent’s experiences — of all the decisions, small and large, that have led to their shared present. And because a common language is among the first casualties, the path back to one another sometimes vanishes altogether. A permanent estrangement.

When my Italian-born husband and I began planning our family, I surprised myself (and him) by how adamantly I wanted our children to know the Chinese side of their heritage.

Having children both expands and compresses our sense of time. The language and identity I had so easily discarded in my youth are losses I now mourned keenly — and they became the very things I wanted to share with the family I was creating. Three weeks before my daughter was born, I scoured Amazon in an attempt to stock a fledgling library with Mandarin translations of old favorites like Ài mǎ (Elmer the Patchwork Elephant) and Sū sī bóshì (Dr. Seuss). With books, my insufficient Mandarin posed less of a handicap. In their scripts, I could fake a naturalness that my spontaneous conversations lacked.

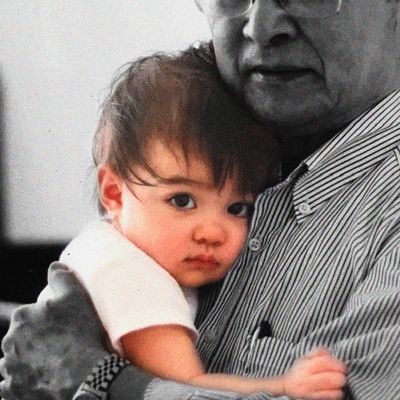

Later, on a hunt for children’s books in Chinatown, I happened upon a cramped storefront, smelling faintly of glue and paper, where shelves groaned under the weight of books. One lunch-hour later, I left with slim volumes of chéngyǔ, or stories based on idioms, and a perfectly tan tea egg the proprietress pressed into my hand. When I recounted the strange encounter to my dad, he laughed in recognition: “I think I used to take you there.” As we shared the egg — its surface marbled with dark lines where the tea seeped through cracks in the shell — I remembered snacking on these eggs as a kid.

I’ve kept apace with my children’s education in Mandarin, memorizing Tang-era poems, watching Taiwanese cartoons, laying down the tracts of muscle memory. Along the way, I’ve managed to resurrect some of what had been lost. I rediscovered idioms that are as much a part of Mandarin as its five basic tones — like huàshétiānzú (drawing feet on a snake), the Chinese equivalent of “gilding the lily” or duìniútánqín (playing a piano for a cow), a version of “pearls before swine.”

But for every excavated memory, others are irrevocably lost. When I found myself longing for my grandmother’s sticky-rice spare ribs (nuòmǐ zhēng páigǔ) or yellow chives and minced-pork stir fry (jiǔhuáng suì zhūròu), I turned to the internet, carefully reading each review to identify the most authentic rendition. And after my kids returned from school one day, excited about the coming Lunar Year, it was with my classmate’s “lǎo wài” ringing in my ears that I conferred with Wikipedia on typical holiday customs. I was a tourist, an impostor. The task I had set for myself felt like, at times, trying to teach someone to paint the Mona Lisa with a stick-figure rendition as reference.

Then came the wave of anti-Asian hate and crimes of the past two years — another crisis of identity. The victims look like my parents, my grandparents, my aunts and uncles. They look like me. Alyssa Go, a 40-year-old consultant, was pushed to her death at a subway station I once passed through on my daily commute. Christina Yuna Lee was stalked and killed in a Chinatown apartment located on the same narrow street where my mother used to live. Vicha Ratanapakdee was struck on the head while out on an early morning walk, something my parents do every day.

But at the same time, I felt a disconnect. I couldn’t actually see myself, my family, in these horrifying tragedies because I didn’t understand enough about who we are to even know what to look for in others. In the stories of these immigrants and their children, whose continent-crossing journeys were snuffed out in an instant, the threads of my family’s story feel just out of reach. Both reticent, my parents have revealed little about what their lives were like before my brother and I were born. Of my father’s childhood in Taiwan, I only know that it had been “difficult,” marked by frequent moves in the face of shifting fortunes; while my mother admitted just once to the loneliness she felt as a 14-year-old Hong Kong transplant, living in Manhattan’s Chinatown with my grandmother. Part of this is the Chinese tendency to minimize unpleasant backstories and jump to the triumphant conclusion: the children with doctorates, the hard-earned homes, the abundant grandchildren. But in editing our stories, we edit who we are. And we rob our children of the opportunity to really know us, and — by extension — themselves.

C.N. Le, a senior lecturer at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, who studies the assimilation trajectories of different Asian American groups in the U.S., tells me I’m not alone: “In the context of anti-Asian hate, a lot of Asian Americans of all ages have been prompted to take a look at their identity and what it means to be Asian American, many for the first time.”

When my parents immigrated to America and chose to raise children here, I don’t know if they wondered who we’d become. “Nǐ shì zhōngguó rén (You’re Chinese),” my dad would say, firm and resolute, whenever I’d ask why I had to give up my Saturdays. I envy that certainty, but as my experience and that of many of my peers show: Gardens need tending. And I worry that my children, who are juggling multiple identities, may someday feel adrift, without a sense of belonging anywhere. But despite my fears, maybe a looming identity crisis isn’t inevitable for them. “It’s easier now than ever for young Asian Americans — whether they’re mono-racial, mixed-race, or adopted — to find others like them and construct their own identity,” says Le. And the tools I’m equipping my children with now could contribute in unforeseen ways in that construction and perhaps grant some grace to my younger self.

On a summer evening soon after our standoff — in which I managed, by the way, to persevere — I’m walking behind my daughter and dad. Her arm is extended slightly to support his leaning gait, and I can hear snippets of their conversation, most of it in Mandarin. “Guò mǎlù shí, xūyào xiǎo xīn (Be careful crossing the street),” says my dad, an oft-repeated refrain from my childhood. “Wǒ zhīdào, Gōnggōng, bié dānxīn (I know, Grandpa, don’t worry),” my daughter replies. It’s a simple exchange, remarkable only in its ordinariness. But hope blooms suddenly within me that my children will always know who they are and where they came from, even if the road to that knowledge isn’t always linear.