Sarah, who is 33 years old and lives in Tennessee, has spent the past few weeks deciding whether to undergo elective sterilization. After they suffered a bout of heart failure as a result of a virus in January, their OB/GYN told them their heart would likely not be strong enough to sustain a pregnancy. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe, Tennessee’s near-total abortion ban is set to go into effect at the end of the month. “Being in a red state, my life will be in danger if I get pregnant,” says Sarah. “I can’t guarantee that I’d have access to an abortion even with medical reasons.” After consulting with their doctor, they decided to have their tubes surgically removed.

Getting your tubes tied or removed has long been common among those who already have children and don’t want more, with around one in four American women getting the procedure. In the wake of Roe’s fall, Sarah is one of an increasing number of patients without children seeking elective sterilization. With abortion bans going into place across the country, people who can get pregnant have been scrambling to secure birth control by stockpiling Plan B or rushing to get IUDs inserted. But fear and uncertainty around the future of reproductive rights — including contraception access — is prompting others to turn to more permanent solutions.

“Our phones have been ringing off the hook since Roe was overturned with patients wanting to come in for IUDs, Nexplanons, and tubals,” says Dr. K., an OB/GYN in Iowa who spoke anonymously because her health organization does not allow her to comment publicly on Roe-related issues. “I have patients who say during counseling, ‘Yep, IUDs and Nexplanons are not for me; I want my tubes tied.’” Tubal ligation, also known as “tying the tubes,” is a procedure in which the Fallopian tubes are clipped or cauterized, eliminating the possibility of pregnancy. The surgery is minimally invasive — it’s typically performed either laparoscopically or after a C-section — and it reduces the risk of ovarian cancer too. Patients can also elect to have a bilateral salpingectomy, a similar procedure in which the Fallopian tubes are totally removed, sometimes to treat ectopic pregnancies or endometriosis. (The hysterectomy, in which the uterus is removed, is another sterilization surgery; it can help treat heavy periods and fibroids, pelvic pains, and certain reproductive cancers).

The recent demand for tubals has been significant enough that Dr. K says she’s had to add extra clinic days on weekends. (Iowa has the least OB/GYNS per capita in the country, making it harder for people seeking the procedure to get it. Dr. K says a nearby Catholic hospital doesn’t provide any form of birth control for patients, which is standard under religious directives). She says many of her patients are concerned about losing access to contraception in the future, so they “just want to get it done and over with.” Tubal ligation is currently covered by most health-insurance plans, though some patients fear that could change post-Roe. “This is a moment of emotional crisis for a lot of patients,” Dr. K says. “They feel devalued, that they’re not in control of their bodies, that nobody cares about their own lives, needs, and desires.”

Even in blue states, doctors are seeing an influx of patients requesting the surgery, including those who already have kids. After giving birth to two children, Jenna, a 34-year-old nurse in Maryland, had been planning to get a tubal. “It’s always been that thing I said I’d get around to, like getting a tooth filling or an eye exam,” says Jenna. “When Roe was overturned, I told my husband, ‘I can’t wait anymore.’ It lit a fire under my ass.” Abortion is still legal in Maryland up to the point of fetal viability with exceptions for fetal anomalies or if the mother’s health is endangered. But with conservatives making clear their intentions to enact a national ban, Jenna says the future feels uncertain. Her surgery is scheduled for this week.

But doctors say many patients currently seeking the procedure have never been pregnant — and want to make sure they never will be. After the Dobbs draft leak in May, Haley, who is 28 and lives in Texas, became anxious that birth control would be next to go. As someone who has never wanted to have kids, she found solidarity in the r/childfree sub-Reddit. “Birth seems extremely painful to me, and my partner and I aren’t financially stable enough to bring another life into this world,” she says. Haley always wanted to get a tubal, but the end of Roe made the decision feel much more urgent: “If Roe hadn’t been overturned, I probably would have stayed on birth-control pills for maybe another five or ten years. But then it was overturned, and I was like, I’m doing it right now.” Living in the Bible Belt, Haley worried her doctor might deny her the procedure because she didn’t have children. She came prepared to fight for her rights and was surprised when the doctor said, “Your body, your choice.”

It’s not uncommon for patients — particularly younger women who don’t have children — to encounter obstacles when seeking elective sterilization. The r/childfree sub-Reddit is full of stories from those who say they’ve been denied tubals because they’re under 30 or because of a doctor’s personal pronatal beliefs. Dr. M, a gynecologist in Florida (who requested anonymity as a practitioner in a red state), says he’s seen a number of young patients who have been turned away by other practices after being told “they’re too young or they need to have a child first.” Some doctors who deny younger patients the surgery point to studies that suggest around 28 percent of patients who get tubals eventually regret them. (It’s possible to reverse a tubal, but it’s generally not covered by insurance, and the success rates for pregnancy after the fact are only 50 to 80 percent, dropping as you get older. During presurgical counseling, doctors advise tubal patients that should they decide to get pregnant in the future, they’ll likely need IVF). But Dr. Taraneh Shirazian, a gynecologic surgeon at NYU Langone Health, suspects that much of the data on sterilization may be biased, pointing out that many study surveys assume anyone with a uterus wants and will have children. “They all talk about, ‘Are you done completing your family?’” says Shirazian.

Other doctors require signed permission forms from a patient’s partner to do the surgery. Dr. K recalls a doctor at her practice who refused to give a woman a tubal after her C-section because her husband wouldn’t agree; the woman later came to her office pregnant. “I was shocked that this could happen in this day and age.” Dr. K believes in providing the service to anyone who wants it and has administered tubals to patients of varying life circumstances, including mothers in their 40s and “a woman in her early 20s who was so terrified about the prospect of pregnancy that she had never had sex.”

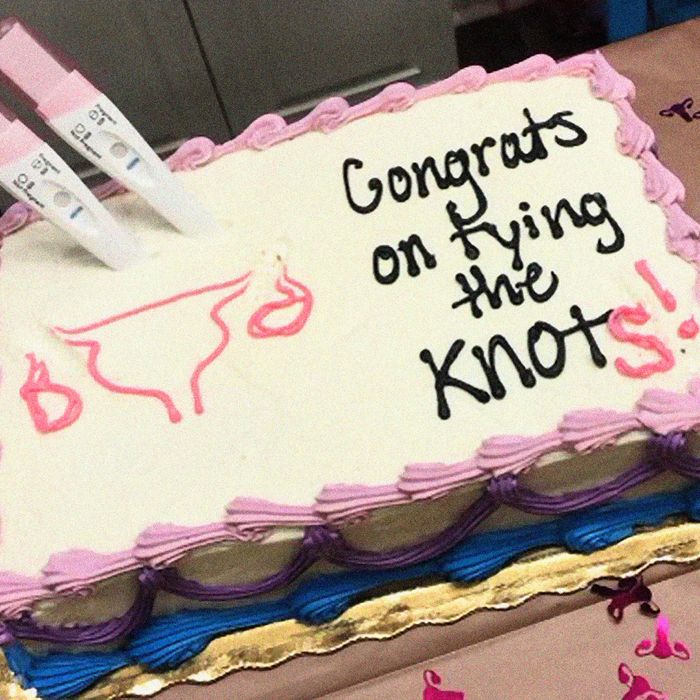

Even those who find doctors willing to perform the surgery may still encounter resistance. Isa Ruiz, a 23-year-old from Orlando, recalls a clinician raising doubts as they were wheeled into the OR. “She was asking me, ‘Are you sure about this? You’re really young. Do you already have kids? What are you going to do if your husband wants kids?’ And I was like, I’m on the operating table. I already have anesthesia in my bloodstream. This is inappropriate for you to ask at any point but especially right now.” Ruiz, who had the procedure in 2021 following years of painful side effects from both birth-control pills and an IUD, says they felt “relieved and thrilled” afterward. “I was like, This is probably the best thing that I’m ever going to do for myself.” To celebrate, they bought a grocery-store wedding cake, which they decorated with uterus confetti and an icing revision: “Congrats on Tying the Knots.”

Yet while getting a tubal can feel liberating to some, doctors also expressed concern that patients choosing sterilization as a result of draconian abortion bans isn’t necessarily a win for reproductive freedom. “The first week I noticed this happening, I felt like, Oh my God, now everyone has to have sterilization because they’re so concerned about what’s going to happen and living in fright,” says Shirazian. “It’s a slippery slope of rights; you get one taken away and you don’t know what’s next.” While some patients find elective sterilization empowering (or simply medically necessary), the procedure has a fraught history, with Black women being forcibly sterilized at disproportionate rates. Even now, more than 30 states have laws allowing the forced sterilization of people with disabilities, and incarcerated people are frequently sterilized without their consent.

But after talking with patients, Shirazian says she’s come to understand that the permanence of the procedure can be a “power move” for some. “Patients tell me, ‘I’ve always wanted this. I need this. People have denied me this.’” In a country that shows less and less respect for bodily autonomy, Shirazian takes pride in honoring it. “My patients come back and say this procedure has helped them. As a doctor, that’s really all that matters.”