Edward Enninful had no plans to write his memoir. That changed in 2020, when he was confronted with prolonged moments of introspection, as well as global protests to bring light to the continued anti-Black violence perpetrated by the police.

“I felt like it was time,” said Enninful, the British Vogue editor, over the phone from his home in London.

Born in the Ghanain port city of Takoradi, Enninful was inspired by his mother, a seamstress who ran a successful dressmaking business, who was distinguished by her ability to mix-and-match Western and West African fabrics. Beyond the home, Enninful found inspiration in Black American publications like Ebony and Jet that he’d source through his aunt. Black beauty, in all of its iterations and fantasies that those particular magazines could create became a fixation for Enninful, one that has fueled him throughout his 34-year career. When he was 13 years old, he moved to the U.K. as a refugee. Three years later, he was scouted as a model by Simon Foxton. At 18 years old, he was hired at i-D magazine. He became the youngest senior staffer at i-D in its most definitive years: “Everything I learned there serves me today,” he said.

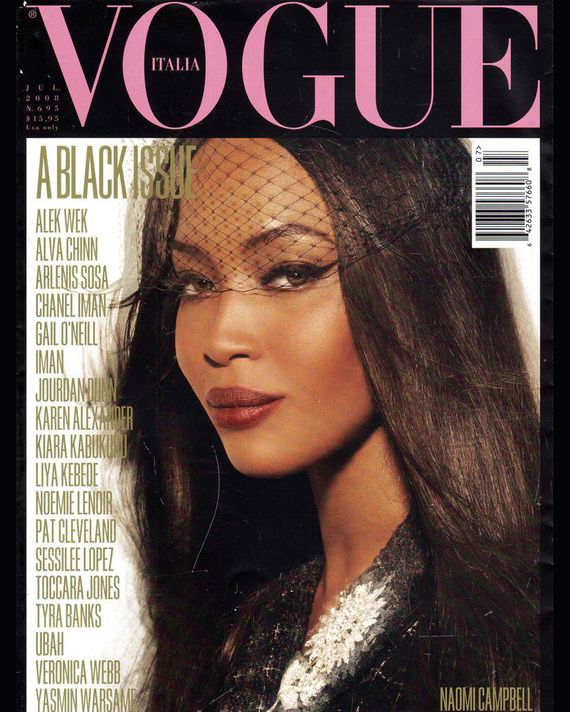

He continued to do that work at Vogue Italia, where, alongside makeup artist Pat McGrath and photographer Steven Meisel, he would create some of the most renowned and recognizable images in the history of fashion. Some examples of that work are the famed “Black Issue” for Vogue Italia in 2008, which sold out its original print run in three days; “Makeover Madness, (2005) a visual commentary on the boom of surgical procedures at the time”; and “Belle Vere,” (2011) which featured three plus sized models on the cover. Today, Enninful champions diversity on the covers and in the pages of British Vogue.

All this work is chronicled in his memoir, A Visible Man, out today, which he describes as the journey of “a boy from Ghana making his way in a racist, classist industry.” After reading the book, I would describe it as a window into a long-standing, uninterrupted, high-stakes life in fashion and what it took to get there.

It wasn’t always easy. “I got here not because of my successes but also my knockdowns that made me keep going,” said Enninful. “Some of the moments were hard to recollect.” He’s talking about how his road to one of the most coveted positions in fashion media wasn’t, and still isn’t, often afforded to Black and brown people.

Enninful recollects these memories, like in 2013 while covering couture fashion week in Paris with the W Magazine team, two designers sat him in the second row while his white colleagues (who held the exact same title as him, Fashion Director) were sat in front. He expresses sentiments, familiar to most Black people in the professional world, like imposter syndrome and self-doubt. In the memoir, he writes: “We know all the stereotypes about us intimately, and jump through hoops — social, psychological, emotional — to counteract them on the job. We know them because one of the most crucial survival skills for any Black person in a white space is to intimately understand how institutional white psychology works. In addition to knowing our own minds and hearts, we have to absorb the dominant culture, how it thinks and reacts. To go into any white space without that comprehension is like walking into a sword fight without a rapier and shield.” To me, this reads as a calling to continue my own work.

You don’t need an official prerequisite in fashion to enjoy A Visible Man, but if you do have an interest in the fashion world, you will certainly be familiar with the models, photographers, designers, makeup artists, and other formidable players mentioned throughout. The Kates, the Naomis, the McQueens, et al. All close friends and family of Enninful’s, and all who have made significant contributions to the trajectory of his career.

The Cut spoke with Edward Enninful ahead of the release of his memoir.

What did your process look like as you were bringing together your memoir?

I just sat down and thought of all the important moments in my life, things that meant so much, moments that propelled me here. I don’t just mean successful moments. I mean moments that were scary, you know, like having sickle-cell trait and thalassemia, and not having the best vision. Those moments, that’s how I started. I knew I wanted to create something that wasn’t just a fashion-gossip book. It wasn’t about that. There was too much that I wanted to talk to the next generation about, and how I wanted to relate to them as well.

One of the catalysts for getting the book off the ground was the protests going on worldwide in 2020 to combat anti-Black police violence. At the same time, a lot of brands and publications were making pledges to combat anti-Black racism and/or advocate for their existing Black employees. Outside of the work you do, have you noticed a change in our industry as it pertains to Black people receiving opportunities?

I can see a change visually: when it comes to models, advertising, runway. And that’s all sort of the surface stuff, but what I’m really championing is employing people from diverse backgrounds behind the scenes. We need people from mid-level to work their way to the very top. Sometimes with interns, the culture of a place will not allow an intern to go all the way to the top. So that’s really what I’m pushing for, that all those pledges have to be met.

Your mother had a thriving atelier when you were growing up in Ghana. How did having such an up-close-and-personal view of garment construction and managing a business affect you?

I grew up around not just my mother, but aunts, grandmothers, nieces — all beautiful Black women of different shapes and sizes and skin tones. I was a kid just taking it all in. It was like being in Willy Wonka or something like that. I was taking in all this beauty. That really informed my idea of what is beautiful and how I see beauty in all kinds of women. And my whole career, I just didn’t want to conform to that one idea of beauty.

Are there things you learned as a young editor at the start of your career working at i-D magazine that you implement today in your work as editor-in-chief at British Vogue?

I’d say everything I learned at i-D I implement today. I would style the covers. I would write headlines. I’d be in the art department working on layouts. I would be in advertising, helping sell. I would write the shopping pages. But I learned everything on the ground. I talk about imposter syndrome in the book, and while I was doing all of this, I was still dealing with it. What am I doing here? Am I supposed to be here? So it was a really incredible time. On the other hand, I’ve never been more tortured — but you are at that age. There’s no escaping that.

Everything I learned now serves me today because now I’m running not just a magazine, but essentially a brand. I had such great mentors: Terry and Trisha Jones and Simon Foxton. I believe that it’s also my duty to pass it on. So mentorship is really, really important.

In the book, you talk a lot about operating in mostly white fashion spaces, working through imposter syndrome, and subverting the system in the best ways you could. What advice can you give to Black people working in fashion who have to navigate similar things?

You will face knockdowns all the time, but that cannot deter you. You’ll probably see your white counterparts get ahead, but your time will come — do not give up. If this is your passion, do not give up. I had so many downs, but it’s those down moments and learning from them, as well as the highs, that got me here. Also, make contacts. You guys have Instagram, whereas we didn’t have that back then. You can find your people and form communities. That’s very important.

What was it like transitioning to creating high and artful concepts at Vogue Italia to then go to American Vogue, where a lot of your output was more commercialized?

I learned the art at Vogue Italia. Steven Meisel would create these 30-page stories based around plastic surgery, and then when we did “The Black Issue.” Franca [Sozzani, the late editor of Vogue Italia] used to say “DO! DO! DO!” And I learned about commerce at American Vogue, how the industry could be powered by business. Every day I try to merge the two in the best possible way while staying true to myself and true to culture.

You speak very candidly about your experience in Alcoholics Anonymous and how you managed sobriety as your career was ascending. Were you ever apprehensive about revealing that part of your journey to the readers?

Alcoholism affects everyone, from the most normal person you could find on the street to the wealthiest; it doesn’t matter. I know so many people are suffering, and if that message can help anybody, that’s really great. There are so many people suffering in silence. It was important that they saw my journey.

I was working; I was a functioning alcoholic, so it never affected my work. It was that emptiness you feel inside. When I was 30, I decided I needed to get my life on track. So for the next 14 years I decided I was going to focus. I was going to get into spirituality. It was one of the best decisions I ever made in my life.

Once you were appointed to British Vogue, what were some of the pillars that you knew you needed to instill within the publication to evolve beyond your predecessor?

I remember in 2017 there was the popular notion that, oh, you know, “Black models don’t sell covers.” I just knew the magazine needed to reflect the world that I was seeing, a world that was diverse in every sense. For me, it was taking Vogue back to the 1970s, when it was about real women in the magazine that real women would look at and see themselves in and be able to relate to. If you see it, you can be it. So for me that was paramount, and I was willing to get fired for it. But the brilliant thing was, now everyone talks about diversity, and it’s so great when you look back — in 2017 it wasn’t a conversation being had. I also didn’t feel like I was doing anything out of the ordinary; it was just something that needed to be done. It’s not a thing to see people from different backgrounds in Vogue anymore. And a whole new generation, that’s all they know. I’m very happy about that. If it didn’t work, there was no way I was going to tiptoe around and try to recreate Vogue in somebody else’s image. That wasn’t part of my agenda.

Can we expect another book from Edward Enninful? Perhaps something for our coffee tables?

Oh, are you reading my mind? There is another … along those lines.

A Visible Man is now available for purchase.